War Stories: Hostage of Paradox

A chapter from Hostage of Paradox: A Qualmish Disclosure

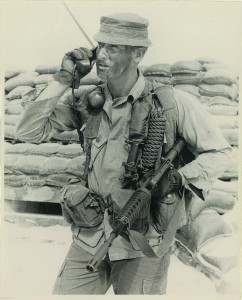

John Rixey Moore (Col ’66) served as a Special Forces team leader in Vietnam, taking part clandestine reconnaissance missions “deep in the jungles of enemy-controlled wilderness.” Virginia Magazine is pleased to offer the first chapter of his new memoir, Hostage of Paradox: A Qualmish Disclosure.

Read our feature, "War Stories."

I remembered the exact moment that my seat on this flight became inevitable. Just a month before, I stood in what would turn out to be the last of many morning formations at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Moments after I had reported my platoon present or accounted for, Sergeant Major Fant stepped forth and began handing down the day’s orders. Fant, with his chiseled features and immaculately tailored uniform, could have stepped out of a Special Forces recruitment poster. He was the quintessential Green Beret. Handsome, professional, and a combat veteran whose service in Vietnam was behind him, he was the ranking NCO of the company and, if not exactly the commanding officer, was unquestionably the psychological head of the unit.

At the end of the day’s mundane list of assignments, he shifted his cold green eyes, pointed directly and unmistakably at me, and said one word: “Vietnam.” I knew right then that whatever might come of this unwelcome news, my life would never be the same.

Now I was irretrievably, depressingly, on the way. Despite over three years in the Army, I had resisted the military’s efforts to wear down my sense of independence enough to maintain a vestige of individualism–or at least of what I regarded as the remnants of my old pre-conditioned self. Though most of the men I served with in Special Forces were “lifers”, that is, guys who saw the military as a career, there were some like me whose private reaction to official attempts at imposing service protocols beyond obeying orders was essentially that of civilians in uniform. Yet now, trapped in an airplane, bound to a common fate with so many others, I began to feel slender layers of myself slipping quietly away beneath the hopelessness and the uniformity. I had become anonymously undifferentiated from the others. I knew I had been reduced by training and equipment to a quasi-mechanical, interchangeable part in the whole monstrous enterprise, a reflection of the success of human mass production and the equipping of armies.

Trapped within the ferocious indifference of such huge logistical processes, the borders of my former familiar world lost their definition. The way I thought of myself began taking on a nebulous and transparent edge. It occurred to me that I had somehow, through some process I could not name, at some undetected moment—perhaps when I had climbed the ladder to the aircraft—been transmogrified into one of history’s nameless GIs. I had not thought of myself in just that way before, not even after nearly four years in the military. Of course there had been many joking references to the term “GI” over the years, but in a moment of painful existential alarm I came to see that I was being herded onto the pages of America’s history of war as just another G.I: Government Issue; One Each; Olive Drab. Utterly expendable, instantly replaceable, and with vestigial individualism suppressed beneath the time-tested rites of military protocol, I had become all but lost in a faceless abstraction of serial numbers.

Over time, a tour in the military succeeds in drawing solitaries together and dissolving their singularities in the face of shared challenges. The child I once had been drew inexorably nearer the edge of the void, saw the blackness there, and somewhere during the night, fell slowly adrift among the shifting fragments of paradigm. Like some hapless mariner from another time, I was the unwilling hostage of enormous forces, which now converged toward that dark region near the margin of ancient maps labeled, “Here bee strange beests.”

The barracks rumor and apocrypha that preceded the flight had supercharged the air, and despite my efforts to ignore scuttlebutt, I was slowly burying myself in morbid images of my own death, which warped and writhed before me, demanding attention and capturing my imagination in a paralyzing collision of mind and heart. I had a book along, but could not keep these thoughts from their insistent intrusion on any reading. For hours I stared out the window at the endless steel-grey sea until even that was swallowed whole by an insidiously deepening night. The darkness quickly closed about me like some implacable malevolent force with a brooding and inscrutable intention of its own.

I don’t think I feared the fact of death, which, as the ultimate unknowable, I found hard to expect as a reality, but I worried about the method of it. How would I face it? Would it be a quick flashing blind shot through the head, or might my end instead come in a screaming agony of dismemberment in some dark, blood-spattered corner of jungle while my companions looked on with helpless indifference?

Yet from time to time my efforts to suppress the furtive parade of these images brought forth prolonged seizures of another naïve certainty that, no, I would be fine after all. That sort of violent end only happens to other people. I’m too, what?–agile, decent, free of malice, educated, well trained, or just plain lucky (fill in the blank)–to die in Vietnam.

It was July 27/28, 1968, somewhere beyond the international dateline and farther from home than I had ever been. My twenty-fifth birthday had come and gone the day before, during through-processing at Fort Lewis, Washington. Some birthday present.

The flight was long and oppressive. The tedium lay not so much in the duration as in the dull, kinetic threat that lay somewhere ahead in the night. It was difficult not to think about it. Vietnam and whatever dangers it held waited out there in the dark, an immutable beast, ancient, and humped out of the sea like the abrupt landscape on a Chinese scroll, its smoky yellow eyes fixed upon me.

We were being transported in a converted air freighter, chartered by the government from the Flying Tiger Line, and fitted with seats as a troop carrier. It had even been equipped with a few apprentice air hostesses, who floated incongruously along the corridor with self-conscious cheer in a cautious pantomime of tentative assistance, their crisp and colorful clothing whispering among us with excruciating irony. With their curiously reserved attentions, they seemed like glamorous technicians in some experimental botanical laboratory, tending to the needs of rare, poisonous vines. Yet, it was they who belonged in the rarified atmosphere of soft lighting, automated temperature control, and scented air. We, citizens masquerading as soldiers, misconstrued in the government-issued clothes and hermetically sealed in an aluminum chrysalis far above the oxygen, were simply passing through the elaborate metaphor.

I had a left-side window seat where, unable to read for the endless hours, I stared out across an empty burnished sea that stretched away so far to the south that it blended into nothingness in misty layers of vapor along the curvature of the earth itself. The engines filled the cabin with their continual drone, while outside my window the seascape passed slowly behind us in ponderous silence.

As the day began to fade, the scale of the view, the very breadth of its panorama, rather than having the effect of freeing my spirit from the confines of an aircraft full of uniforms and uncertain destiny, instead began to press in upon me with the full weight of my own insignificance. My sense of aloneness deepened. I tried to send my mind loping back along the years of my life in search of sunny memories from any time not freighted by dread. A few scenes of home and of younger days came gamely forth, but the comfort I hoped for, the sense of self I sought there, was not in them. The heavy uncertainty of my situation, the looming presence of whatever lay ahead, pressed in upon all my efforts to think about other things like a low-intensity headache. I could not escape the feeling that something profoundly unpleasant had already singled me out from the crowd and was waiting now somewhere in the night, patiently tapping its claws.

In the long, crowded solitude my gnawing fear gave way periodically to grapple with a growing curiosity about the coming day and what I would find there. Like struggling creatures, neither fear nor my curiosity could prevail, and neither would withdraw.

Outside, the starlit ocean seemed oddly tipped beneath the encroaching gloom, as though its conjectural lines of longitude gathered ahead like drawstrings. Behind us and a little to the south, a red moon rising slow in the east came up through layered clouds like a crooked smile, and as a deeper darkness closed in around us, lightning began to stitch up its distant folds with pale fire.

In the momentary light that flashed through the clouds of a distant storm I thought I glimpsed the Beast of my imagination. A vein pulsed out there, and almost imperceptibly, two ominous plates moved together, dusky tiles of armor in the fierce cold flicker. As we rushed on toward some distant collected point of fury beneath the vast and relentless sky the whole cloak of night came down upon my tiny hopes and fears.

We were retracing the route taken far below us in 1942 by men just like ourselves who rode in rolling, sweltering troop ships. Many of them had been bundled into eternity in the first quick chaotic moment they stepped ashore, and during the hours of that night with nothing to see out the window, I wondered again what our own arrival would be like:

We would probably land at night, I thought, likely drawing fire on the runway. Then, under covering perimeter fire, we would be hurried into underground bunkers by way of a trench dug into the earth alongside the runway, and would undergo our first briefings there, perhaps with moist dirt, loosened by incoming rounds, sifting down through overhead logs. Indoctrination by newsreel tends to animate the expectations of those who are faced with the prospect of a featured role in one.

Through the night the flight attendants practiced their professional smiles on those who were awake. They had to. This was not the sort of duty anyone with any airline seniority would have taken. Despite occasional rousing outbursts among a group of men seated near the front of the plane, there was little talk. An atmosphere of quiet introspection seemed to prevail; or perhaps that was simply my own contribution to the stillness.

Self-conscious conversation and easy teasing drifted between the girls and some of the men. A pang of envy for the girls’ attentions sagged through me, and in that strange aquarium world of silences and undercurrents, it shifted again my alternating awareness of their presence. Inept at talking to girls anyway, I could think of nothing to say and so drifted in private twilight for hours, while struggling with an undeniable urge to memorize their movements as diminishing remnants of all romantic fantasy. By the time the long flight ended, I had not spoken a word to any of them, hoping that silence at least had the virtue of a certain colorless dignity, which is the only substitute for constructive ideas on unhappy days.

Hostage of Paradox: A Qualmish Disclosure by John Rixey Moore, © 2013 (Bettie Youngs Book Publishers), is a Pulitzer-Prize entry, a Colby Award contender and “USA 2012 Best Book” award winner. Reprinted with permission from the publisher BettieYoungsBooks.com. Available on-line at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.