The University and the Civil War

New book offers a fictional account grounded in fact

Which of the following is true:

- Monticello once hosted medieval-style jousting, the riders hot-blooded Cavaliers.

- Civil War-era Virginians believed all beautiful girls were sweet and all ugly men knaves or cranks.

- The illegitimate son of Edgar Allan Poe, Class of 1826, was a Yankee spy.

- In 1865, a UVA professor named Socrates surrendered the Grounds to Col. George Custer using a bed sheet as a flag of truce.

Answer “All but C” and you may be a fanatic weekend re-enactor of the Civil War or, like novelist Nick Taylor (Col ’98, Grad ’05), share a fascination with the arcana surrounding the University during that period.

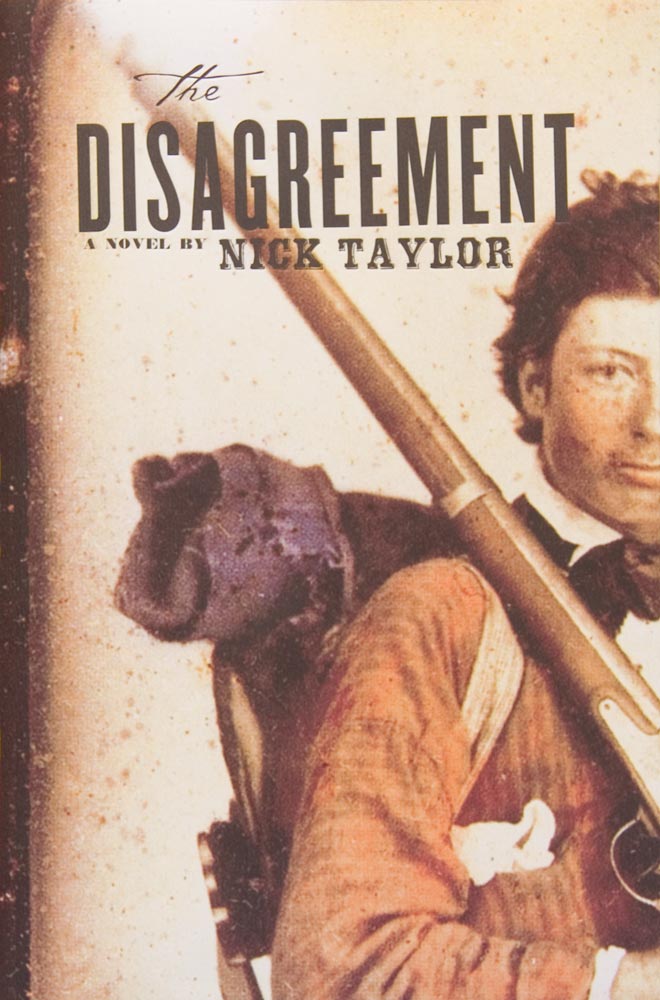

Taylor’s new book, The Disagreement, draws on such bygone events and real-life figures at UVA for highly readable fiction grounded in fascinating fact. “A confluence of the war novel, the campus novel and the coming-of-age story,” according to Taylor, it localizes the national war epic, seeing it through the startled eyes of an idealistic medical student growing to manhood while turmoil encroaches on the Academical Village.

Rich in evocative detail about University life during the 1860s, Taylor’s story offers a convincing picture not only of an army but also a society imperiled. The novel opens on that fateful April day in 1861 when Virginia declared secession; what follows is the tale of John Alan Muro’s transformation from naive teenager to expert healer tending a fraction of the 620,000 fighters who died in the war, two-thirds of whom perished from diseases like measles and syphilis rather than gunfire.

At the Virginia Festival of the Book in March, Taylor participated in a panel discussion on Civil War fiction and offered insight into the specific genesis of The Disagreement—its title a genteel Southernism for the fratricidal fury—and the craft of historical fiction, the popular offspring of a storyteller’s art and a researcher’s industry.

In the book, Muro’s father runs the Bedford Woolery, ramping up to suit Confederates in 10,000 sack coats of battlefield gray. Seeking steadier income, the father had exchanged the profession of medicine for that of commerce. Disappointed in him, the son resolves to succeed as a doctor by training at the renowned Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia. Flashing sabers and roaring cannon, however, make transit across the Mason-Dixon line impossible, so John Muro settles for the 40-year-old University of Virginia.

Taylor spent many long nights in the Special Collections Library to boost the necessary verisimilitude of his book. He concentrated on the period diary of Louisa Minor, a prototypical rebel belle who mused about life on Pantops Mountain, and on nuggets mined from Charlottesville and the University of Virginia in the Civil War, a 1988 study by Alderman librarian Ervin L. Jordan Jr. “I’m completely indebted to Jordan,” Taylor acknowledges. “I tracked down every one of his footnotes.”

One such note, in fact, provided him his jousting scene. He embellished the reality somewhat, adding buglers playing “Dixie,” lance-wielding horsemen garbed in blue and gray, and melodramatic dialogue. Another chapter in Jordan’s book, “A Confederate Hospital,” furnished the novel’s setting. And sources as various as soldiers’ letters home, newspapers, legal documents and home-front journals helped deepen the novel’s background. Medical histories, for instance, introduced Taylor to the dubious doctrine of “psychogenesis,” which holds that countenance and character exactly correspond. So middlebrows, at least, of the mid-18th century did indeed believe that physical beauty reflected metaphysical virtue—and that ugly is as ugly looks.

History itself sparked Taylor’s initial creative fire. As a student in the graduate creative writing program, he recalls spying a wall plaque during a walk around town that mentioned that the University had become a war hospital after the battle of First Manassas. Shortly thereafter, Taylor penned a grant proposal to the William R. Kenan, Jr. Trust for Historic Preservation, offering to undertake not an architectural or archaeological study but something more offbeat: fictional stories about UVA’s past.

With grant money in hand, Taylor wrote three: about Poe and the “ne’er-do-well sons of local politicians,” he says; about UVA in World War II; and, his writing workshop’s favorite, the 30-page tale that eventually became the 460-page manuscript of The Disagreement. (His editor at Simon & Schuster cut 100 pages—“without sacrificing any of the story,” Taylor says in grateful admiration.)

In grad school, while Taylor had developed a passion for the lyrical flair of William Styron, his own writing focused on modern-day foibles. “I was working on ‘The Sex Life of Country People,’ a series of humorous and insightful stories about odd folks you meet in the country—girls who go to the farmers market to pick up farmers—things like that,” he says.

But historical fiction, he discovered, afforded him a host of ready-made heroes, villains and fascinating incidents, and better still, the literary excitement of capturing the language of the time. “I’m a good mimic,” he says, “but I didn’t want my prose to be as turgid as 19th-century prose often is. So I combined today’s syntax with old-fashioned word choice.” He consulted the Oxford English Dictionary to avoid anachronisms—“‘Okay’ and ‘nope’ can’t creep into the story,” he says—vetted combat scenes with his father-in-law, a military historian, and tweaked his characters’ concerns to make them palatable to modern readers.

“Yes, this is a slightly altered version of the past,” he concedes. “For one thing, people back then were almost obsessed with religion. About 90 percent of [Louisa] Minor’s diaries were about church life and praying. On occasion, I regret not concentrating so much on religious life, but the story had to move forward. You can’t include everything.”

In The Disagreement, the protagonist, Muro, sets up digs on the East Lawn, Room 52, and befriends Braxton Baucom III, an Old Dominion grandee sporting a beard in “the distinctive style of General ‘Stone Wall’ Jackson, cut square like a sow’s tongue and twisted into points on the end.” In time, the earnest medical student and the decadent sport vie for the hand of Lorrie Wigfall, a woman smitten with Strauss’ waltzes and Longfellow’s poetry. Based on Taylor’s wife, Jessica, she’s the steel-magnolia niece of UVA’s professor of anatomy and surgery, James Lawrence Cabell. (Cabell was a professor in the School of Medicine from 1842 to 1889.) Whether presiding over the Anatomical Theater, a Jefferson-designed edifice that was demolished in 1939, or kneeling to pray in the family pew at Grace Church in Cismont, Cabell represents Taylor’s most successful use of a real-life character. From him emerges not only the muscular Christianity of a Southern patriarch but also the even intelligence and resourcefulness of a man of science.

For drama’s sake, Taylor invents a rivalry between Cabell and Dr. S.P. Moore, the actual Confederate surgeon general, but underscores Cabell’s characteristic objectivity when the doctor overcomes his initial resistance to Moore’s mandate that folk remedies replace the hospital’s dwindling store of pressed opium and quicksilver. Here, Taylor’s eye for detail shines as readers learn of warriors treated with dried fleabane, yew leaves, sassafras root bark and lemon grass.

Save for Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, Taylor steered clear of most Civil War fiction while writing his own, maintaining that he’d neither read nor viewed Gone With the Wind until after he’d finished. And true to its locale, his isn’t chiefly a war novel.

Charlottesville saw no action more major than the February 1864 skirmish at Rio Hill, site now of a shopping center. Confederate militia turned back Custer that time out, but the iron-willed colonel would soon prove their nemesis. On a March morning a mere month after the fracas, faculty chairman Socrates Maupin surrendered the University to the invader. One of Taylor’s more moving vignettes sets the scene: “There had been news from the Shenandoah Valley via night rider that Sheridan’s army, which had laid waste the whole area from Winchester to Staunton, was moving east.” Rather than risk the school’s torching by the vengeful Federal, Maupin negotiated with a conciliatory Custer and won a reprieve for the University and Cabell’s hospital. Muro’s tale essentially ends with Maupin’s white flag, although an epilogue tells us that, ever the Southern loyalist, he refused a postwar offer to fulfill his boyhood dream, that of practicing medicine in Philadelphia.

Nick Taylor’s next move? While he’d entertained notions of taking his writing in a more contemporary direction, his agent and publisher have persuaded him to stick with enlivening the past. And so the Los Angeles native, an assistant professor of English and comparative literature at San Jose State University, is writing a new novel about Padre Junipero Serra, the fabled Californian missionary. Historical fiction, he feels, is where he’ll make his mark.

Inside The Disagreement

Captured best perhaps by Matthew Brady’s photographs, the savagery of the Civil War was truly harrowing. Bayonets and musket volleys did their awful work; so, too, did rampant sickness. Here, Taylor’s protagonist serves as a kind of Everyman witness to its effects:

“No one should have to see what I saw: men with bits of case shot peppered all over their faces like cloves in a roast: men whose filthy eyes were black with infection and swollen to the size and glaze of billiard balls; men whose last ounce of early life was spent trying in vain to form the word Mother with lips deadened by tetanus. I read once about a king in ancient China who refused ever to weep for fear of losing the life carried on his tears. I was scared to cry, but there was no life in my tears, only salt. And I could no less afford to lose that.”

Careful to ground his account of blood and battle in a palpably distinctive world, Taylor is just as adept at detailing the manners and mores of the 1860s South as he is at rendering the violence that undid them. Ladies of the Farmington social scene are thus described:

“Any account of Albemarle County during this period is sure to pay significant attention to these [Farmington] women. To the young ladies of the area, these women, who were mostly of the elderly persuasion but included a few young wives given entrance by dint of good birth or good marriage or both—these women were the envy, the very idols, of every girl for miles around. They carried themselves like the old English aristocracy, which was likely what they believed themselves to be, venturing into the public eye only on certain predetermined and highly orchestrated occasions, such as the Governor’s Ball in spring (indeed, the governor always made an appearance, as he had every year, since the office was held by Jefferson himself). Like English aristocrats, too, the Farmington women cloaked themselves in a vast mythology of historical and genealogical lore. That Jefferson had designed their temple, the main house at Farmington, was beyond questioning—in fact, our third president had lent his hand to a number of private homes in the area, but of these only Farmington wore the association as a badge.”

In this passage, Taylor details his main character’s introduction to his eventual home away from home—UVA:

“The vast Lawn was divided into terraces, each separated from the next by a path of bricks. Like opened arms, the colonnades stretched south, marking the distance with the black doors of dormitories and bejeweled now and again with the broad porticoes of professors’ homes … We crossed the Lawn on the southernmost path. My dormitory was the last door on the east colonnade, adjacent to the final pavilion … The chamber was modest: a small brick hearth occupied one wall, two stained pine bedsteads lay against the other. Against the far wall—under the window—was a writing table and a light button-backed chair.”