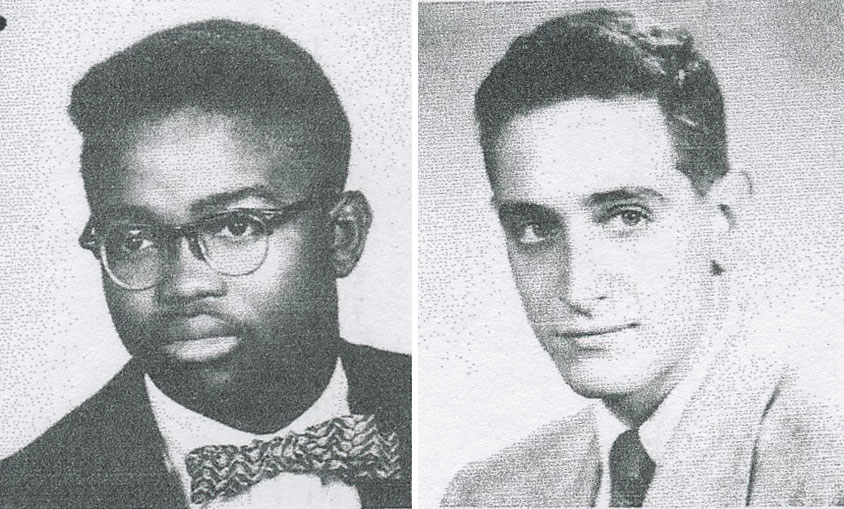

Memories of a football weekend, in black and white

I wish my old pal Charlie would have lived to see it. A black guy wrapping up two terms as president of the United States. Who’da thunk it? “God bless you, and God bless America,” as they say from the podium. It would have been Charlie’s dream come true.

I had looked forward to seeing Charlie at our 50th high school reunion in 2003, but he wasn’t there. A classmate told me he had been in the hospital, suffering from Parkinson’s and other elder indignities. And then he was gone.

You move away. Life goes on. We just lost track. We hadn’t seen each other for years, not since that painful football weekend a lifetime ago in Charlottesville.

Charlie and I grew up in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, then a smoky, blue-collar city on Raritan Bay. Through the 1940s and into the ’50s we played with slingshots and Daisy BB guns, worked in a car laundry together and played on the same public school basketball and baseball teams. Upon graduation from Perth Amboy High School, we both headed to Virginia, taking our predetermined paths—he to Richmond, to the historically black Virginia Union University, and I to Charlottesville, to the all-white University of Virginia.

Eighteen years old and naïve from my integrated upbringing, I invited Charlie over for the Cavaliers’ first football weekend. This was September 1953. Martin Luther King Jr. was just 24 and Rosa Parks had not yet boarded that bus.

Charlie boarded his in Richmond and, he later told me, was asked to move to the back. I met him at the downtown depot Friday afternoon, in time for the pep rally and bonfire, and, of course, the drinking.

For me, the transition from small-city slicker to Southern gentleman was a leap. I soon learned that the clothes I’d brought down with me could have been added to the first football-weekend bonfire. There wasn’t a Shetland or Harris tweed blazer in my wardrobe. The sports jacket I did own was a Robert Hall special. It came with two pairs of pants, neither of them khakis. Argyle socks had never wrapped my feet, blue cotton oxford cloth my back, nor silk rep my Jersey Boy neck.

But as out of place as I was, I was at least the right color. And after spending nearly an entire semester’s budget at Eljo’s and Stevens-Shepherd, the two clothiers on the Corner, I could blend in. So much so, I got elected president of my fraternity.

But that would take another two years. First semester first year, I was completely “out to lunch,” an expression I was not meant to have heard, but did hear several times.

I wasn’t supposed to have heard “Charlie Chocolate” either, but soon after my old pal stepped off the bus, and together we walked back to the dorms, the first chill of discrimination pierced the September air.

The weekend was a total bust, and I felt Charlie’s pain. Blacks in C’ville were, in 1953, relegated to the Vinegar Hill section of town. Their presence on Grounds came about either for cafeteria or maintenance work or as musicians playing in small bands in the fraternity houses on weekends.

The post-game parties ran into the night: kegs of beer and live music everywhere. We hit three or four of them, up Madison Lane, down Rugby Road. It was the same wherever we went: Being ignored and rebuffed was bad enough, but there were too many smug looks I know I shouldn’t have seen, and some racial epithets I shouldn’t have heard.

I could sense that my old friend was not himself. It was still early, as we walked up Lambeth Lane from yet another fraternity house party when Charlie said to me, “I think I should head back tonight.”

“I’m sorry, buddy,” I said. “This isn’t Perth Amboy, is it?”

We walked down to the depot so he could catch the late bus back to Richmond.

“You tried,” he said. “And who the hell won the game, anyway?” It made me smile. Before leaving, we gave each other a hug.

If Charlie had made it to that high school reunion, I would have given him another one. And if he could have hung in there five years after that, to see our country elect its first black president, we would have given each other a high five, right after sharing a good laugh about that inglorious weekend.