Deep Rooted

A look at the University’s shady side

If the University of Virginia’s landscape were to represent the human mind, with the Rotunda and pavilions being our most sophisticated thoughts, what better to represent our imaginations, where we ponder and dream, than the trees? Vibrant in the light of a spring afternoon, blazing with color in the fall, the trees at UVA compose a major part of the University’s personality. They’re woven into our memories of spending time on Grounds (who hasn’t marveled at the changing leaves while marching to the library?) and with their chapel-like peace, add to the meditative atmosphere of the University.

While it seems like the trees have been here forever, their health and layout is no accident. Like everything, they take management and care and can be threatened by factors that seem beyond our control. Also, as the Grounds continue to evolve with major additions such as the South Lawn Project, how will the landscape, the trees, evolve with it?

First, a little history. “The land the University was built on was an old farm,” says Mary Hughes, landscape architect for UVA since 1996. “The ground was relatively infertile, which made the land available at an affordable price … so there were no trees except for at O-Hill.” Whether trees were actually meant to be planted on the Lawn has sparked some controversy. Some claim that the trees block views of the pavilions and interfere with Jefferson’s neoclassical architectural plan for the Academical Village. However, an 1817 letter in which Jefferson sketched the village and in the middle of it wrote, “grass and trees,” seems to settle the debate.

“We do know that the first trees were black locust trees,” says Hughes. “The first pictures of the Lawn show dead or dying black locust trees.” The intention was to interplant them with longer-living hardwoods such as the maple and ash, which now make up the predominant species on the Lawn. The oldest trees are believed to be the sycamores on the north side of the Rotunda. “We believe they were planted before the Civil War,” says Hughes.

It’s not surprising that Jefferson included trees in his plans for the University. According to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, he distributed seeds of North American trees to European friends during his time as minister to France and, later, his white pine and hemlock plantings earned him the distinction of being “the father of American forestry.”

With such a long history, there are trees at UVA that hold a sentimental value—those that took root in the hearts of their stewards. The McGuffey Ash is one such tree. Planted in the garden of Pavilion IX in 1826 (just one year after the University opened for classes), the tree is said to have been protected by the wife of professor William E. Peters, who lived in the pavilion from 1874-1903. According to legend, she sat at the base of the tree and told workers who threatened to cut it down (to lay sewer pipe) that they would have to cut through her first.

The tree had to be removed in 1990 due to old age; however, feelings ran so deep that plans for perpetuating it in some way already existed. In the late 1980s, when the McGuffey Ash was still living, branch cuttings were grafted onto ash rootstocks. Of the eight that survived, one of the saplings was planted where the original tree stood in 1996.

“Another really fabulous tree is on the west side of the Rotunda: the Pratt Ginkgo,” says Hughes. This was the University’s first memorial tree and was planted in honor of William Pratt, superintendent of buildings and grounds just before the Civil War. “As fall goes on, the tree turns bright yellow. The leaves fall practically overnight, and in the morning, the ground is covered with gold.”

In conjunction with the University’s Arboretum and Landscape Committee, the memorial and commemorative tree program allows individuals to plant a tree in honor of deceased alumni and faculty. Official trees are also planted in remembrance of those who made a significant and lasting contribution to the landscape.

The Pratt Ginkgo is but one of the University’s standout cast of trees. “We have inherited a remarkable collection of beautiful old trees that lend great character to the Grounds that people identify with UVA,” says Hughes. “They’re a treasured part of our heritage.”

But what about when something goes wrong? For instance, when a branch gets too long or a tree nears the end of its life?

Behind the Seeds

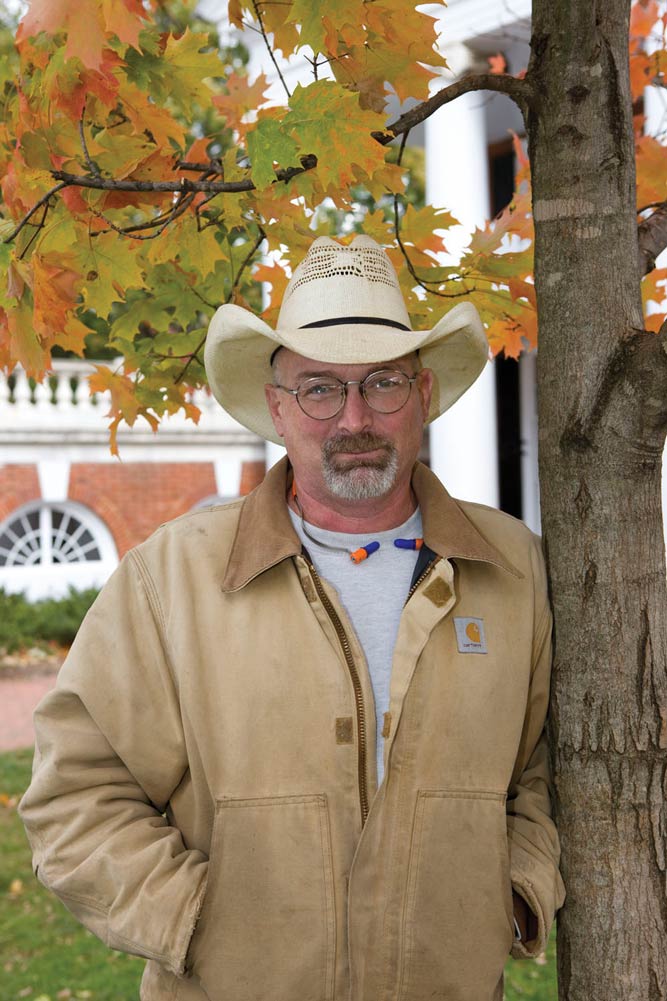

“I see people getting their wedding pictures taken under the trees, I see students sitting there. I don’t think they realize how much work is involved in maintaining the trees’ health. They do have a caretaker,” says Jerry Brown, an arborist at UVA for 14 years.

If you think of trees as the other population at UVA, you get a picture of what can go wrong. “Trees are like people,” says Brown, “every day there could be a problem.” Trees that hollow out from the inside, limbs that die back (rot so much that they could fall) and storms that leave branches in the road are just some of the issues that have to be dealt with. Just like students, trees change as they get older. “Through the stress of the seasons, there could be soil deficiencies,” says Brown.

And there are those trees that have special problems. There’s the ginkgo tree, for instance. Though a beautiful tree, the female of the species produces a fruit that when fallen and decomposing emits a smell that isn’t exactly floral. “If you were to step in it, you’d probably think you’d stepped in something else,” says Brown.

Then there are dangers that have nothing to do with the internal nature of the tree or the caprice of the weather, but that are shiny and green and probably came on a ship from Asia. The emerald ash borer is an insect that has killed at least 25 million ash trees, many of which have been in Northern Virginia. “It’ll probably be in this area soon and will put a pretty bad hurting on the ash trees around here,” says Brown. The adult beetles eat the ash foliage, causing little harm. The danger lies in the larvae that feed on the inner bark, interfering with the trees’ ability to transport water and nutrients. “It’s scary because the pest is so devastating. Insects come here from other countries, and they have no predators.” Insecticide can be used—injected into the tree or employed in a soil drench. However, there are no guarantees. “The emerald ash borer will definitely change the tree scene.”

But what of threats that don’t fly or carry larvae? It’s possible that a more immediate danger to the trees on Grounds is expansion. “Probably our biggest pest is construction areas,” says Brown. It’s a fact that new building projects and renovations are a part of the evolution of any university. But when trees dot much of the landscape, unpopular decisions have to be made. “They only give a little bit of space to keep that tree alive,” says Brown, referring to the barrier put around designated trees on a construction site. “The next thing you know, there’s a mystery pipeline that means the tree needs to be taken down. We deal a lot with construction damage.”

As trees grow, weather changes and unforeseen factors come into play, the maintenance of trees on Grounds is a demanding, ongoing job that’s not for everyone. But it has its perks; for instance, take the office view. “Where else can you sit up top of a tree and watch the sun come up a little?” asks Brown. And when it comes to favorites, he would have to pick the white oak. “They’re strong trees during storms; they don’t seem to get pest problems; they get a lot of acorns; and just to look at it, it’s a beautiful tree.”

Branching Out

The South Lawn Project, slated for completion in 2010, will change the face of the University. With such a huge addition to the Central Grounds area, the landscape is a major initiative and provides a blank canvas to be painted with trees. A spectrum of species will be planted, including white, red and willow oaks; paperbark, red and sugar maples; river birches; European beeches; green ashes; sweet and black gums; and tulip poplars, to name a few. Through clever placement, the trees will provide benefits far beyond their aesthetic value.

“Trees are critically important to the landscape plan for the South Lawn Project for several reasons,” says Cheryl Barton, landscape architect for the project. “The large scale and height of the building complex (four to five stories) required large trees to mediate its size for pedestrians as well as for adjacent neighbors.” Not only that, but shade provided by the trees creates cooler, “micro-climate” zones in the summer. In the winter, branches slow down cold winds. Other considerations include placing deciduous trees on the south and west sides of the building that will allow sunlight in the winter and prevent overheating in the summer, thereby enhancing energy efficiency. Also, “Large street trees are placed along Jefferson Park Avenue to create an urban streetscape edge,” says Barton.

Another main feature of the South Lawn Project will be the Catherine Foster burial site. Catherine Foster was a free black woman who lived there in the 19th century. The memorial, made up of two parts (the family burial ground and the original homesite), will include Virginia flowering dogwoods and white oaks. “It appears that the original home was in a circle of white oaks,” says Mary Hughes. “We’ve gone to great pains to try to preserve trees and incorporate them as part of the cultural landscape.”

The young trees of the South Lawn Project will help usher in a new era for UVA. If the past is any indication, they will be embraced and appreciated as a part of the community of nature that surrounds and suffuses Charlottesville. They’ll grow with the University, anchoring us in time as we reach toward the future.

Discovering Virginia’s Trees

For sumptuous photographs portraying a wide range of Virginia trees, check out Remarkable Trees of Virginia, published by the University of Virginia Press. Combining the photography of Robert Llewellyn (Engr ’69) and the prose of Nancy Ross Hugo and Jeff Kirwin, the book offers scientific insights as well as the history of some of our state’s finest trees. Of the 1,000 trees that were originally nominated for inclusion in the book, the authors selected a lively sample of Virginia’s myriad species, from the oldest to the largest to the truly unique, such as a willow oak in which you can find an embedded tricycle. From an American beech in front of Sleepy Hollow Methodist Church in Falls Church to a bur oak in Elkton, you’ll also learn about trees that are part of Virginia’s history. Far from a textbook, Remarkable Trees instills a fresh appreciation for a part of nature that’s often taken for granted.