War Stories

Generations of alumni reflect on military life

The past century has seen two world wars and major American operations in Asia and the Middle East. UVA alumni have lived through all these conflicts, and experienced firsthand how military service has changed with different geopolitical strategies and advances in technology. Some things, though, have stayed the same. James Austin (Col '49), Eric Gyauch (Engr '82), Ellen Gyauch Davis (Med '86) and A.W. Simmons (Col '09) all learned about the cultures and people of the countries where they worked. Some saw loss of life and the costs of war to the injured. From a military family herself, Davis went on to study how deployment affects families and children.

Today only 1 percent of American citizens serve in the U.S. military, yet their service shapes the lives of all Americans. "It's important that people know what it's really like," says Simmons. "Every day, members of the armed forces are doing real work—work that not only directly impacts the lives of the people they lead but also the long-term security prospects of our nation."

World War II

On the night of April 27, 1944, James Austin's ship sailed into the English Channel as part of Operation Tiger, a dress rehearsal for the invasion of Normandy—a plan that called for British and American boats, under the command of Dwight D. Eisenhower, to land on the long, wide sandy beaches of the English coast.

Austin's ship, an LST 57 (Landing Ship, Tank)—a flat-bottomed vessel designed to support amphibious missions—was carrying tanks and troops toward Slapton Sands, a beach in England. "We called the LSTs 'Large Stationary Targets' because they'd get stuck on the sand during low tide. We'd have to wait until the next tide came in to move them back out to sea," says Austin (Col '49).

It was five weeks until D-Day, and although he wouldn't know it until later, Austin was about to participate in the bloodiest training exercise of World War II.

In 1943, Austin was, he says, "a Southern Baptist farm boy just graduated from Appomattox High School." He'd been trained as a navy pharmacist's mate and his LST also carried two doctors. His ship was a part of Foxy 29 medical evacuation unit, which was later awarded a Presidential Unit Citation. "That night we loaded up and set out into rough waters," says Austin.

What happened next would be kept secret until long after the war was over.

"The Germans knew we were there. Just after midnight, German E-boats fired on and sank three LSTs. We lost more American boys into the cold waters of the English Channel that night than we did on Utah Beach on D-Day," he says.

Austin's ship wasn't hit, but it took on wounded sailors and soldiers, as well as casualties. "They called me 'Morphine Flo,' for Florence Nightingale," he says. "I tended to the wounded and the suffering." By morning, 749 men had lost their lives in the cold water.

"We didn't breathe a word about it for 50 years," says Austin. "It would have been bad for morale, and we had a war to win. To think that we were on some lumbersome thing like an LST, and the whole world depended on it."

"On the early morning of June 6, the sky was dark with airplanes pulling gliders full of paratroopers," says Austin. "We were the largest armada ever assembled in history, headed to the beaches. The battleships Nevada and Texas were behind us, shooting salvos over our heads toward the batteries where the Germans were supposed to be. We could feel the vibrations. We were like a cork in a bathtub."

LST 57 landed on Utah Beach and Austin took a small boat to gather the dead and the wounded from the water and bring them back to the ship. "We filled every bunk with a casualty. We loaded out the tanks, scrubbed down the tank deck and filled it up with men. And we brought them back to England."

Among the wounded were American, Canadian and British members of the landing team, paratroopers who had been dropped inland and fought their way back to the beaches—and Germans.

One was a German pilot, whose plane had been shot down over the beach. "My buddies thought he should be shot, but I didn't agree. The belt buckle of his uniform had the words 'Gott mit uns,' which means 'God with us,'" says Austin. "There's an apocryphal story about Abe Lincoln, that during the Civil War someone said to him, 'Surely God is on our side.' Lincoln said, 'My greatest concern is to be on God's side.' I treated the German. We were all just human beings, hurting, crying and dying."

Over the next few days and into the next few months, LST 57 ferried tanks and troops to France and casualties back to England. "It must have been 40 trips back and forth," he says.

Austin was in London for V-E day—saw "Princess Lizzy," who later became Queen Elizabeth—and in Seattle for V-J day. He went to UVA to study law, but graduated with a degree in philosophy and religion. There he met his future wife, "the flower of Charlottesville," he says, Madeline Staples (Educ '50). After graduating from Southern Baptist Seminary in Louisville, Ky., Austin became a Baptist minister and spent 65 years in the ministry. "I learned in the Navy about life and people," says Austin. "It led me to what I became after."

Sixty-eight years after D-Day, Austin was presented the French Legion of Honor by the French government in September 2012 at the French Consulate in Atlanta.

Relative peace, then conflict in the Middle East

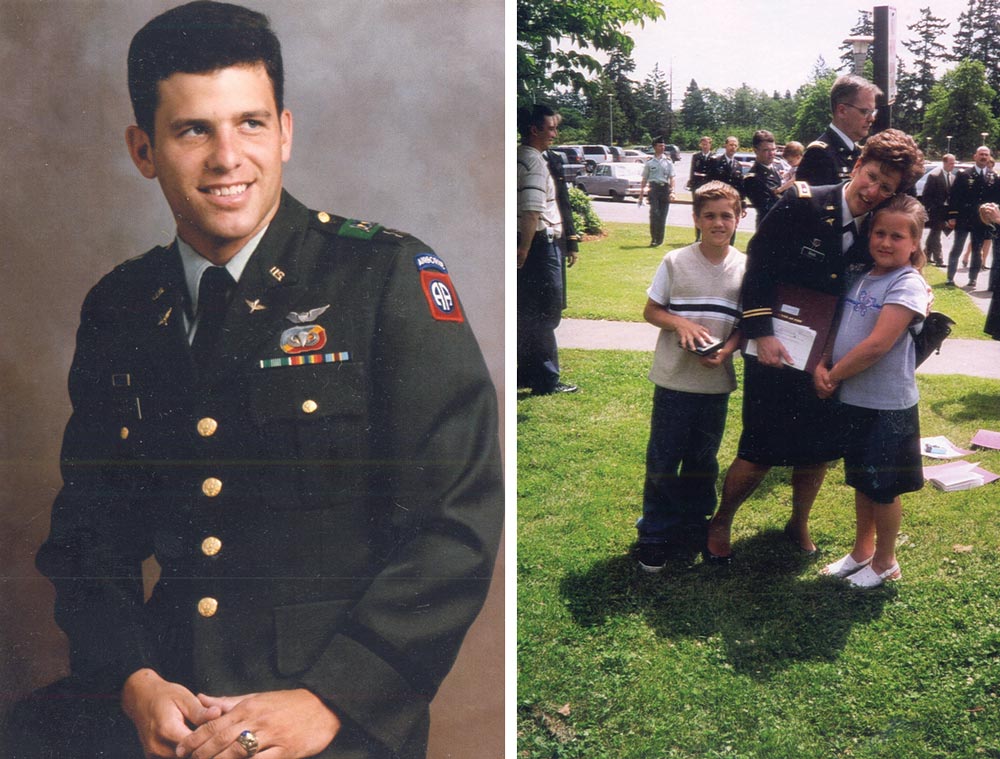

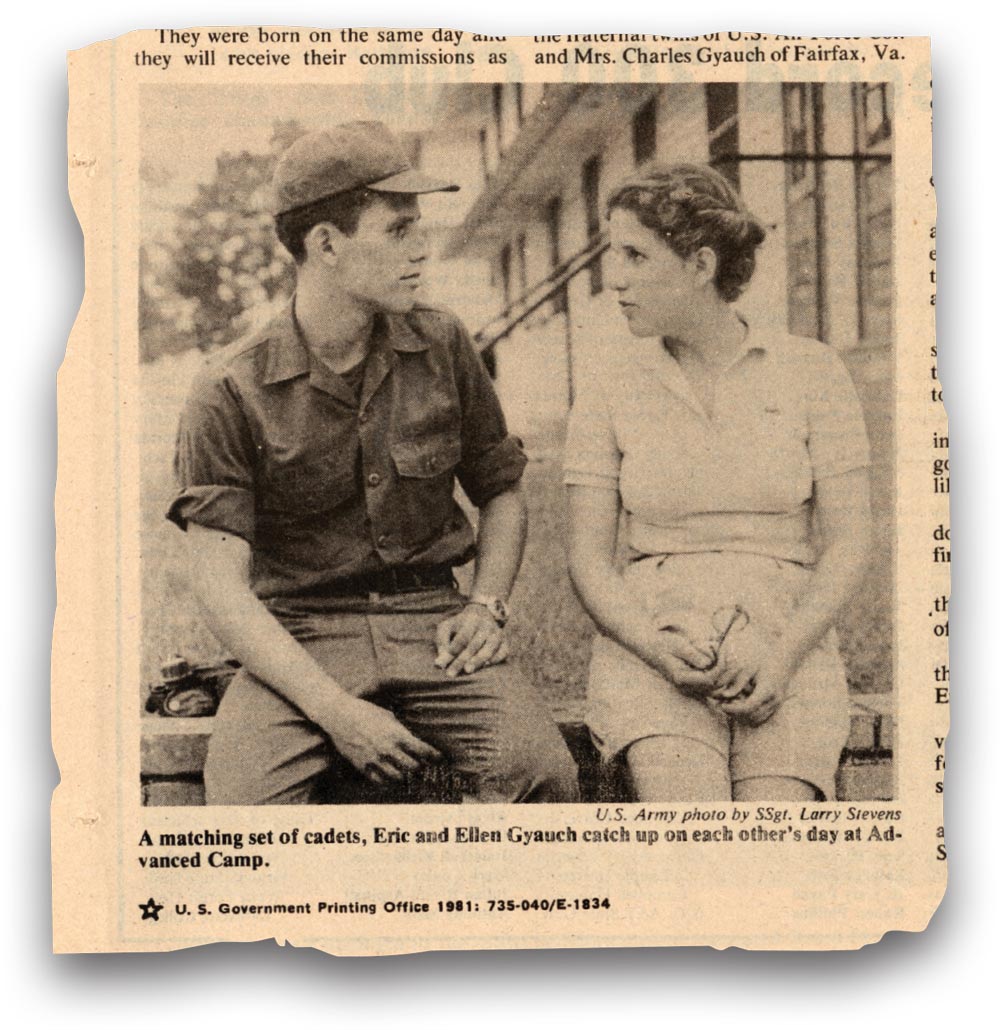

In 1978, Ellen Gyauch (now Davis) and Eric Gyauch, twins and recent high school graduates, were both offered ROTC scholarships. Their father, a U.S. Air Force officer, told his teenaged children, "Don't do it for the money. It's bigger than that."

Davis (Med '86) and Gyauch (Col '82) had grown up on military bases, moving every few years, and their friends were the children of other military families. "We knew the benefits of military service and understood the desire to serve," says Davis, "but what our father was telling us was that the military would get every pound it paid for. In the military, you don't really belong to yourself. You don't belong to your family. It needs you 24/7."

Gyauch attended UVA and Davis went to Davidson College for their undergraduate degrees. The summer after junior year, the two attended training at Fort Bragg for six weeks. Before they left their home in Montgomery, Ala., they had to prepare physically for the challenges of the coming weeks. "We put on our army boots at 4 a.m. every day and ran in the street in the dark," says Davis. Gyauch did well at Fort Bragg. "He was always good at that stuff: orienteering, shooting targets, exercise. I hated all those things," says Davis.

Davis and Gyauch graduated on the same day—their parents driving between their ceremonies—"one of the perils of having twins," says Gyauch. "Then I went right into the service, the day I graduated."

Gyauch became an aviation maintenance officer for the U.S. Army and earned his flight wings. After 18 months of military training, his first assignment was in South Korea in 1983; Seoul was already preparing for the 1988 Summer Olympics. "The U.S. Army has always maintained a strong presence in South Korea due to the threat from North Korea, to maintain peace at the border," says Gyauch. He went to the DMZ, which is the most heavily militarized border in the world. "The South Korean soldiers look directly across at the North Korean soldiers. They faced each other."

Gyauch commanded soldiers who were responsible for fixing helicopters and made sure they were ready for their missions. He also traveled all over Korea to recover military aircraft after crashes. "If an aircraft crashed into a field or a mountain, our Army recovery team would arrive after the bodies had been removed. It was solemn work; often pilots had died," says Gyauch.

After his service in Korea, Gyauch was assigned to Fort Bragg to work with the 82nd Airborne Division, where he earned his jump wings. "My unit, 1st/17th Air Calvary, 82nd Airborne Division, is responsible for rapid deployment anywhere in the world," says Gyauch. During his three years there, the division was often on alert, ready to deploy to nations in Latin America where there was unrest. "But we never did deploy," says Gyauch. "I served during a post-Soviet but pre-Middle East era of relative calm. The '70s had been a difficult time, but the military was regaining its public image. The Cold War was won during this era."

Meanwhile, his twin, Davis, had been attending medical school and doing her residency at UVA. "I took an educational delay to become a pediatrician and then the day after my residency ended I was assigned to Fort Bragg," Davis says.

By 1990, with the first Gulf War on the horizon, Gyauch had left the military to work for Michelin. But Davis was deployed to a unit on the North Sea waiting to join the ranks in Iraq, and her father's words from 12 years before proved true.

"My firstborn was 2 months old when I was deployed," says Davis. In the airport, her husband held her son, Michael, while she sobbed. "I felt like I was giving up this child who was supposed to be mine. It was almost a deal breaker for me, that moment."

The Gulf War ended more quickly than expected, but Davis' career trajectory had been altered by her deployment. She worked as a pediatrician at bases all over the U.S., while she researched the medical needs specific to military families.

"During the first part of the 20th century, because of the draft, most soldiers were young men without families. But since the early '70s, when the military became an entirely volunteer force, the demographics have changed," says Davis. "More soldiers have families and stay in the military for a career."

Davis was scheduled to make a presentation about her fellowship research on Sept. 12, 2001, but it never happened. "We were put on immediate alert," she says. "Then I put away all my research for the next few years, and focused on the war."

It became clear to Davis that someone needed to study how a prolonged military engagement affected military families. She and her fellow researchers traced how parental deployment affected children's mental and physical health. "The single most important factor affecting a young child during a parental combat deployment is to find out how the at-home parent is doing. Supporting the at-home parent supports the child and family, as a whole." As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wore on, Davis' work also revealed that multiple deployments take an even greater toll on service members and their families. "It does not get easier because a family has done it before."

Her work was referenced in President Obama's "Joining Forces" document, which outlines a national initiative to support and honor America's service members and their families. Davis retired in 2009, as a colonel, after 20 years of service.

Battling back from injury in Afghanistan

Mortar attacks came regularly during the day at Army 1st Lt. A.W. Simmons' outpost in the Pech River Valley. "You can engage an enemy from 5 or 6 kilometers away with mortars," says Simmons (Col '09). "We'd take mortar fire twice a week on average. And the enemy would send an observer up in the mountains to direct the rounds in, thus the need for daylight."

Exchange of rifle fire was common both during the day and at night. "We were in direct firefights with insurgents about every other day," says Simmons.

Simmons was deployed to the Kunar Province of Afghanistan in April 2011, where he was the officer in charge of a remote outpost called Nangalam Base. "The size of three or four football fields, it was an encampment with old brick buildings, some plywood shacks, all surrounded by HESCO barriers, which are big cages filled with dirt that make a thick wall."

Simmons commanded about 50 American soldiers and mentored 100 Afghan soldiers on the outpost. "Our work was a combination of the hard-handed combat you expect in the infantry, as well as coordinating with local Afghan governance to build capacity and expertise," says Simmons. Six to seven hours day, Simmons was "outside the wire," actively patrolling the Pech Valley. Another seven hours were spent training the Afghan army in tactics and techniques. "I typically didn't sleep more than four hours a night."

Simmons liked the intensity of the workload and even the stress of working in a dangerous place. "It was life squared. Or life cubed. Every day mattered very deeply." He joined ROTC at UVA because he had known since he was a teenager that he wanted to serve in the military. "My dad was a JAG officer, and he'd been at the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C., when Flight 77 hit the Pentagon," says Simmons. "He heard the sound of it. So, like a lot of people of my generation, 9/11 impacted me and how I imagined my future."

On Nov. 21, 2011, Simmons' outpost came under mortar attack. "Mortars are high-angle bombs; you fire them out of a tube about 4 feet long, and they shoot out of the tube at a high arc," he says. Simmons and his men were preparing to go on patrol when the attack began and, as was his routine, he started running toward the operations center so he could start coordinating the counterattack and update his superiors some miles away.

From the Archives: Vietnam

Laurie Croft (Col ’67) arrived in Vietnam in 1969 as a 2nd Lt. in the U.S. Army.

“I joined an eight-man advisory team in Vinh Binh village,” Croft wrote in a Spring 2000 feature story for Virginia Magazine. “The team house (aka hooch), which was built of plywood, tin and screen, reminded me of a summer camp cabin.” On “movie night” the team watched The Graduate. “Twenty minutes into the movie, as Miss Bancroft was preparing for her soul-baring scene with young Dustin Hoffman, the team members abruptly left their seats. My fixation on Anne Bancroft was interrupted only by the sounds of exploding mortar rounds bracketing the hooch. I hit the floor and crawled instinctively toward the already full in-house bunker.”

A mortar hit the ground behind Simmons, about 15 meters away, and threw him forward into the dirt. His legs were filled with shrapnel. "I knew my legs had been hit badly, but I was able to roll over and see they were still there," says Simmons. The noise of the explosion left him temporarily deaf as he crawled toward the first aid station about 60 meters away. "It's a bad idea to stay in the same place during a mortar attack," says Simmons.

His men heard him "screaming my head off" and carried him into the first aid station. "They saved my life, and I owe them everything."

No one else was hurt in the attack. Simmons was evacuated to a military hospital near Asadabad, then to Kabul, then to Germany, and finally to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

His doctors told him it would take six months for the layers of muscle in his legs to knit together and to regain full range of motion in his now-shortened hamstring. "I really wanted to get back downrange and finish out my deployment with my men," says Simmons.

By February, three months faster than expected, Simmons was cleared for service, but he wasn't sent to the front lines. Instead, he was sent to Hawaii to work as an escort and Gold Star family liaison. "When someone dies overseas, his remains are never allowed to be left alone. As an escort, I wore my full dress uniform, rendered proper honors at every transfer of remains, and escorted my fallen comrade to his final place of rest."

Between late February and early April, Simmons' battalion lost three men out of 11 total over the whole deployment. "I was the escort for Army 1st Lt. Clovis T. Ray. He had been my replacement leading the platoon on my outpost." Ray died on March 15, 2012, of injuries caused by an improvised explosive device.

Simmons continues to serve in the infantry. After serving for eight months as second in command of an infantry company, he is currently in full-time training to compete in the 2013 Best Ranger Competition at Ft. Benning, Ga., an annual competition among the Army's Rangers to find the best two-man Ranger team in the Army. His battalion is currently slated to return to Kunar Province in July 2013.