Constitutional Crossfire

How a student gazette landed UVA at the high court

When UVA turned down a request to fund a Christian student publication three decades ago, it believed it stood on solid legal ground: a set of guidelines rooted in the constitutional separation of church and state.

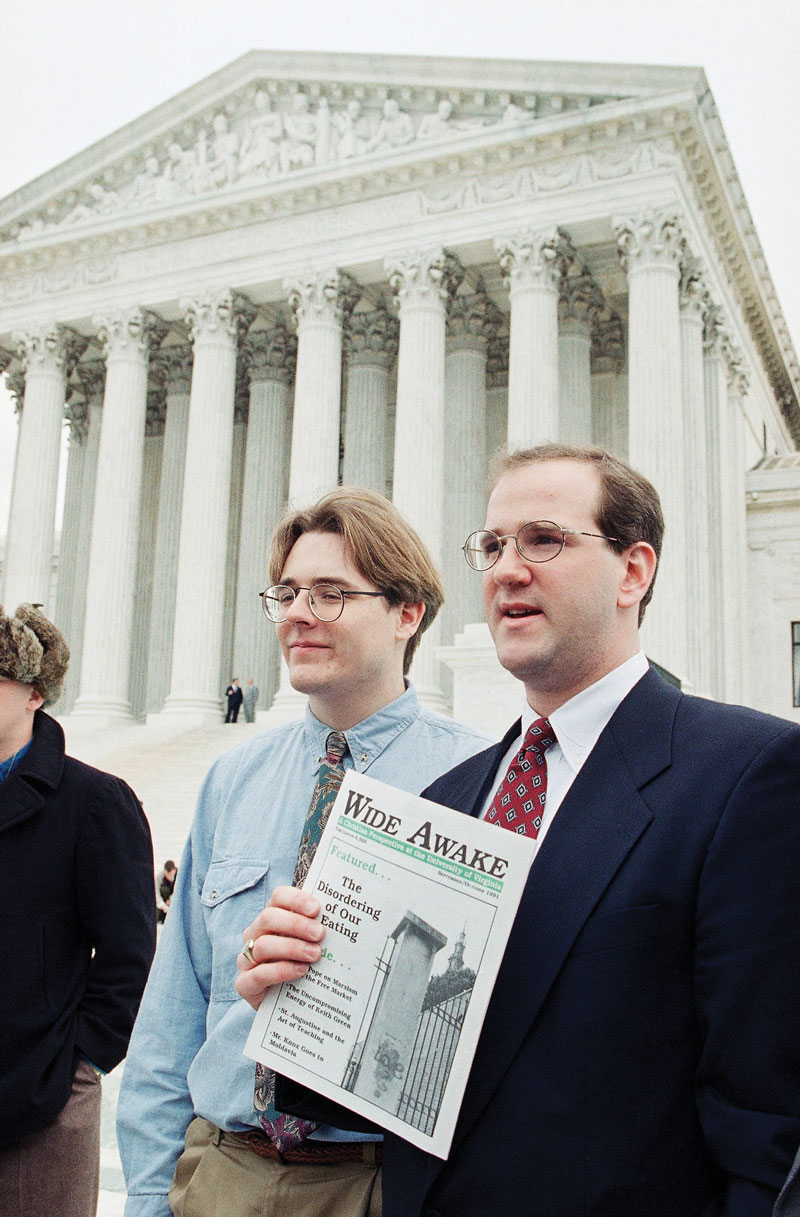

To the students requesting the funding, however, the denial was a free speech issue. If UVA funded other student groups, they argued, it should fund their magazine, Wide Awake.

The students sued. Their case, Rosenberger v. Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1995.

Coming at a time when constitutional law as it relates to religion was being reinterpreted, Rosenberger was from the outset about far more than the $5,862 the students requested. The dispute represented “the collision of two lines of cases,” wrote Rachael Jones (Law ’21) in “Rosenberger’s Unexplored History,” an account of the case published in the March 2021 issue of the Journal of Supreme Court History.

One line of cases, known as “no aid,” held that public funding of religion was prohibited. The other line, “equal access,” said the government could not exclude religious groups from open forums.

Rosenberger was a victory for the equal access line, and one of a series of wins for religious speech and exercise in recent decades. Taken together, they represent a “complete about-face” in the law as it was traditionally understood, says UVA law professor and former dean John C. Jeffries Jr. (Law ’73), who argued UVA’s case before the high court.

“The one thing I learned in studying (constitutional) law when I went to law school: No money can go from the government to an overtly religious activity,” Jeffries says. “The Supreme Court has now turned that on its head. Not only can money go to religious activities; in many cases, it has to.”

Highly publicized at the time, Rosenberger put UVA on the front lines of that cultural and legal battle. Standing on legal principle cost UVA in the court of public opinion, with some inaccurately criticizing the University for things it had not done—such as banning Wide Awake from publishing or preventing Christians from attending UVA.

But standing for what they believed in felt like vindication for the students, says Greg Mourad (Col ’93), one of three who brought the case.

“It was certainly an important victory and very satisfying in the end,” he says.

Mourad met co-plaintiffs Ronald Rosenberger (Col ’92) and Robert Prince (Col ’92, Law ’06) while writing for The Virginia Advocate, a conservative political publication. Mourad was a religious studies major from North Carolina, Rosenberger a political and social thought major from Northern Virginia, and Prince a government major from Virginia Beach.

They soon decided to branch out on their own.

“We were just sitting around one night, and Ron had this idea that he wanted to put his energy into this Christian magazine instead,” Mourad says.

They launched Wide Awake in the fall of 1990. The magazine’s mission was “to challenge Christians to live, in word and deed, according to the faith they proclaim and to encourage students to consider what a personal relationship with Jesus Christ means.” They distributed it free and carried ads from churches and Christian bookstores.

Their long legal journey began in January 1991, when they applied for funding from the Student Council’s Student Activities Fund, as reimbursement for printing costs. The council used mandatory student fees—then $14 per semester—to fund a range of groups, called Contracted Independent Organizations.

The council’s guidelines, set by the Board of Visitors, prohibited funding of CIOs engaged in “religious activity,” defined as activity “that primarily promotes or manifests a particular belief in or about a deity or ultimate reality.”

On the advice of University Counsel James Mingle (Law ’73), the council denied the students’ request for funding.

The students issued a press release the same day. They planned to appeal the decision and go beyond that if necessary.

The students obtained the help of The Center for Individual Rights, a public interest group founded two years earlier. Mourad says he can’t recall if the group was referred to the students, or whether they reached out to the group. Whichever the case, the CIR was eager to get involved.

“CIR appears to have understood early the possibility for Wide Awake to become an influential case, as did the University,” Jones wrote in her journal article. Indeed, former UVA President Robert O’Neil, a constitutional scholar, told Mingle he had an “early sense that this was likely to be one of the most difficult and divisive of cases in the field,” Jones wrote.

CIR assisted the students with their appeal, which seemed to have a fighting chance. Two years earlier, in a case that made national news, the conservative Advocate, where Mourad, Rosenberger and Prince had met, successfully appealed its own denial of funding. The denial had been based on a ban of funding for political activities, Jones wrote. The council reversed itself, deciding that publishing anything was expression, not activity, and that “any publication” was eligible for funding, she wrote.

Wide Awake’s appeal failed nonetheless. The students filed suit in U.S. District Court in July 1991.

Mingle represented UVA, in consultation with O’Neil and Jeffries, an expert in constitutional law. Virginia Attorney General Mary Sue Terry (Law ’73), a Democrat and law school classmate of Jeffries and Mingle, supported UVA’s position. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court, there had been a change in administration, and Republican Attorney General Jim Gilmore (Col ’71, Law ’77) sided with the plaintiffs against UVA, an unusual position given that the school was technically his client.

In May 1992, U.S. District Court Judge James Harry Michael Jr. (Col ’40, Law ’42) ruled in favor of UVA. He held that the Student Activities Fund was not a public forum and that UVA’s denial of funds was not based on Wide Awake’s viewpoint. He also ruled that the school had reasonable fears that it could violate the establishment clause of the First Amendment, which prohibits the government from favoring (or helping the “establishment” of) a religion. And he said UVA had not violated the free exercise clause—which gives citizens the right to practice their religion—and that the school had wide discretion in making funding decisions.

UVA won again when CIR, Rosenberger, Mourad and Prince appealed to the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, but the opinion it issued in March 1994 leaned much more on a strict interpretation of the establishment clause. It said UVA had a “compelling interest in maintaining a strict separation of church and state.”

The decision was a red flag for Jeffries, who thought the court had gone too far.

“By the time of the case, it was clear to me that the [Supreme] Court was leaning away from its historical commitment to the establishment clause,” Jeffries says. “I thought that painted a target on the University’s back. As soon as I saw that opinion, I thought, ‘Well, the court is likely to have something to say about that.’”

When the high court decided to take the case, Jeffries took the lead, writing the brief and preparing for oral arguments.

On the morning of oral arguments, Jeffries took a cab to the Supreme Court building and walked in alone, prepared to face a “hot bench” certain to pepper him with questions.

He steered clear of an establishment clause argument in his brief and in his opening remarks to the court.

“This case is not specifically about religion,” he said. “It is about funding and the choices that inevitably must be made in allocating scarce resources. Some funding decisions do not involve speech, but at a public university virtually all of them do. In public education, funding speech based on content is legitimate, routine and absolutely necessary.”

UVA’s denial of funding to Wide Awake was not based on its viewpoint, Jeffries emphasized. The guidelines allowed for different points of view but prohibited funding for certain broad categories of activities: electioneering, lobbying and religious activities.

“Basically, religious activity means worship services and prayer, or proselytizing, so there is little doubt that this magazine fits the university’s guideline,” he argued.

Justice Anthony Kennedy pushed back. Was any discussion of religious views proselytizing?

No, Jeffries said.

Justice Antonin Scalia jumped in frequently. When Jeffries said there was a long tradition of financial disengagement between church and state, Scalia said: “This is not a church, though.”

Scalia also questioned Jeffries’ use of the term “proselytizing.”

“I don’t know what you mean by proselytizing,” he said. “That’s not what the guideline says. It says ‘manifests.’ ‘Promotes or manifests.’”

On it went.

“You try to anticipate the questions and you try to think of what you would say, but it’s not easy,” Jeffries recalls. “You’re just batting the next ball.”

At bat for the other side was Michael W. McConnell, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School. He argued that Wide Awake was denied funding because of its viewpoint.

“Thus, if my clients this morning were the (Students for a Democratic Society), if they were vegetarians, if they were members of the Federalist Society, or Black separatists or whatever, there would be no need to be here.”

McConnell said the organizations UVA funded did not speak for the University. UVA simply provided a means for them to speak. He argued for neutrality between religion and its competitors in the marketplace of ideas.

He closed by saying that “proselytize” was just an “ugly word for ‘persuade,’” something other groups were guaranteed the right to do under the First Amendment.

Justice David Souter countered that it was one thing to recruit members to an organization and another thing to recruit “adherence to God, to religious tenets.”

The court voted 5-4 along ideological lines in favor of the students. Jeffries had hoped to sway William Rehnquist, but the chief justice voted with Kennedy, Scalia, Sandra Day O’Connor and Clarence Thomas in favor of the plaintiffs.

Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Souter and John Paul Stevens sided with UVA.

Kennedy wrote the majority opinion, concluding that UVA had engaged in viewpoint discrimination in the limited public forum created by the Student Activities Fund. UVA did not need to deny funding to obey the establishment clause, he wrote.

Souter got right to the point in his dissent.

“The Court today, for the first time, approves direct funding of core religious activities by an arm of the State.”

To ensure he’d have a spot in court for the announcement, Rosenberger got a press credential, as Supreme Court correspondent for Wide Awake. He said the ruling was proof that one person could make a difference.

“I believed in what I was fighting for,” he said in a 1995 article in The Virginian-Pilot. “I don’t think Christians should be treated as second-class citizens, and I don’t think Christian students should be treated as second-class students.”

At the time of the ruling, Rosenberger worked for Young America’s Foundation, a conservative youth organization. He went on to work for other conservative groups. Mourad, now vice president of the National Right to Work Committee, says he’s lost touch with Rosenberger, who couldn’t be reached for this story. Prince, who went on to work as an intellectual property lawyer, also could not be reached.

In the wake of the ruling, UVA changed its funding guidelines to remove restrictions based on content. Other universities with similar guidelines did the same.

Rosenberger remains an oft-cited case, Jones wrote. UVA law professor Micah Schwartzman (Col ’98, Law ’05), who was an undergraduate at the time of the ruling, says Rosenberger moved the ball in the equal access line of cases. In the years since, advocates have successfully pushed for public funding for religious schools.

For Jeffries, the case was about a larger shift underway at the time.

“If you want to think of it historically, it’s a decision made right when the tide was going out on the traditional understanding of the establishment clause,” he says.

UVA was swept along with that tide. The resulting sea change in constitutional law regarding religion is “every bit as dramatic and complete as the court’s shift from ‘separate but equal’ to Brown v. Board of Education” was in public education, Jeffries says. He remains convinced that UVA was on the right side.

“I thought—and think—it should have been a winning argument. You can’t say equal access when you’re talking about money, because it runs out. It just doesn’t work to say, ‘You gave money to somebody else so you have to give money to me.’”

Mourad still has a few copies of Wide Awake in his attic. Looking back, he doesn’t blame UVA for taking the position it did.

“We never had any sense of animus for the University,” he says. “They had the sense that this was what the law required of them. We thought the Constitution was on our side.