Renovating the name, too

Understanding what’s behind the push to rename Alderman Library for Edgar Shannon

Editor’s note: Virginia Magazine published this story ahead of the Board of Visitors’ nearly unanimous March 1 vote to rename Alderman Library for former UVA President Edgar Shannon. See our Spring 2024 Letter from the Editor, “It’s Beautiful. What shall we call it?”

After four years and $161 million of construction, Alderman Library reopened to students in January with a conspicuous item still on the punch list—the name over the door. The space is blank.

John M. Unsworth (Grad ’88), the dean of the libraries, had petitioned for the made-over building to be named for someone other than Edwin Anderson Alderman, the University of Virginia’s first president, a figure who was larger than life in his day but whose embrace of eugenics makes him problematic in ours.

Unsworth made his request almost three years ago. A blue-ribbon committee devoted close to two of those years to studying the question and formulating a recommendation. It has proposed transferring the marquee honor to a similarly pivotal University president, Edgar F. Shannon Jr. In his 1959-to-1974 term, he worked to integrate UVA, brought about full coeducation and, amid the turmoil of the Vietnam antiwar protests, earned acclaim for keeping the academic year, the premises and the First Amendment all intact.

After months of consideration, the Board of Visitors said it would vote on the recommendation by March 1, in time for the library’s official grand opening five weeks hence.

It’s the most consequential commemorative naming decision the Board will have taken up since the University began reevaluating the iconography of Grounds over the past several years. No previous issue has involved a building as prominent as the main library or a personage as central to UVA history as Alderman.

It would mark something of a precedent for Shannon too, a major step-up in his recognition on Grounds. In 2013, the University affixed his name to one of the three just-completed new-new dorms, adding him to a crowd of namesakes beside Lile-Maupin and Tuttle-Dunnington, all located, in fact, off Alderman Road.

Putting the name in play

Unsworth submitted his request to Michael F. Suarez, the English professor and Rare Book School director who chairs the Naming and Memorials Committee. Members include former law dean and UVA presidential counselor John C. Jeffries Jr. (Law ’73); former University Rector Frank M. “Rusty” Conner III (Col ’78, Law ’81); former Alumni Association Board of Managers Chair Meredith B. Jenkins (Col ’93); two historians; and current and recent student leaders.

Suarez, a Jesuit priest with multiple graduate degrees, put them through their paces. Unsworth’s submission included a 27-page white paper on Alderman that retired UVA history professor Phyllis Leffler had prepared. The committee didn’t simply check her citations; it went to her sources, and then to her sources’ sources. After consulting Gregory Michael Dorr’s (Grad ’94, ’00) cited book on eugenics in Virginia, Segregation’s Science, the committee retrieved the UVA doctoral dissertation that underlay it, and then it had him present to the committee himself.

“We understood the seriousness of the [renaming] request,” Suarez says. “The committee very much didn’t want to, as it were, take anybody’s word for it. We wanted to do the work ourselves.”

He divided committee members into pairs and gave out assignments. No one was spared. “So, there’s Rusty Conner, the former rector of the University of Virginia, sitting in Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, turning over pages in the Alderman papers,” Suarez says. “And this was iterated over and over again.”

A national figure

The UVA naming policy, the standards the Suarez committee applies, dates to 2008 with several revisions since. Working in Alderman’s favor as UVA’s first and longest-serving president are the policy’s “strong preference” to honor “administrators,” among others, “who have had long, close, and valued associations with the University” and its desire to “recognize distinguished or exceptional levels of achievement.”

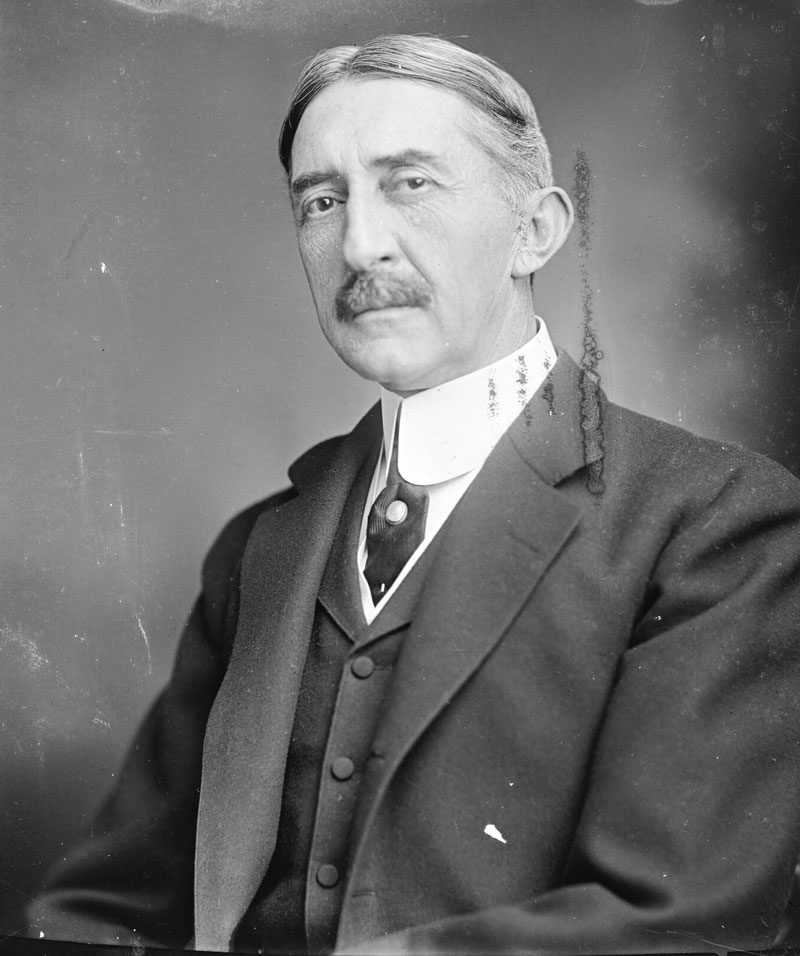

Alderman took on the newly created post of University president in the fall of 1904 having already established a reputation as one of the South’s foremost voices on public education and having served as president of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and then Tulane University.

Over his 27 years in office here, he more than tripled regular-session enrollment to 2,514 and multiplied the endowment thirtyfold to $10 million, according to a May 1931 tribute in Alumni News. He was a master fundraiser, attracting investments from the Rockefeller family to found an education school, from Paul Goodloe McIntire to start a school of commerce, and from Andrew Carnegie for a range of curricular reforms, all while steadily increasing UVA’s state appropriations.

And he was a builder, starting with the president’s mansion he put atop Carr’s Hill, passing on the offer of a pavilion and signaling the assertive leadership style to come. He erected Lambeth Colonnades to upgrade UVA’s football venue, then upgraded it again by constructing Scott Stadium. In the years in between, he put up Memorial Gymnasium. Alderman also expanded the UVA hospital five different times.

He had a gift for elaborate oratory, which helped advance his national prominence, culminating in the eulogy he delivered before Congress in 1924 for his longtime friend Woodrow Wilson (Law 1880). Wilson was one of four U.S. presidents Alderman had hosted over the years on Carr’s Hill, according to a New York Times obituary. A fifth, Herbert Hoover, sent a telegram of condolence upon Alderman’s sudden death in 1931. So did former New York Gov. Al Smith, who had lost to Hoover.

Sixteen days before the need for condolences, Founder’s Day 1931, at what would be his last official University function, Alderman urged UVA to build a new library, saying it would be his pride and glory should he live to see one take form.

Alderman was, in short, the obvious choice for the honor when UVA dedicated a new UVA library in June 1938.

A higher bar

Nearly a century later, renewing Alderman’s library privileges is far from automatic. As a baseline, the naming policy contemplates time limits: 25 years for honorific names (as opposed to those tied to major gifts) with no guarantee beyond that. Alderman’s name has fronted the library for 86. (The presumptive timespan for philanthropy-based names is 75 years.)

Substantively more troublesome for Alderman is the policy’s aspirational language. In several different places the guidelines call on commemorations to uphold UVA’s values—that a selected name “should reflect our values as an academic institution,” that it “serve as a projection of our values,” that it be consistent with the “community values of the University.” In the same vein, “honorees should demonstrate virtues the University hopes its students seek to emulate.” Putting an even finer point on the matter, the UVA naming policy favors honorific names that “consider the University’s mission related to inclusion and diversity.”

Historian Michael Dennis regards Alderman as a prominent example of the self-styled New South progressives who ran the region’s public universities around the turn of the 20th century. “He combined the paternalism and the uplift with the racial control, which is supposed to be the progressive alternative to what was being offered—you know, violence and lynching,” says Dennis, who devoted part of his book Lessons in Progress to Alderman and met with the naming committee.

Alderman expressed his views on racial hierarchy strongly, frequently and at length. A particularly instructive example, just to give a taste of his rhetoric, is a speech he delivered to a near-capacity Carnegie Hall audience in 1908, several years into his UVA presidency. He called denying African Americans the right to vote “the chiefest political constructive act of Southern genius” and defended segregation as “a far-sighted politics of justice, both to the negro as a race, and to the higher groups that inhabit this nation and to civilization at large.”

In 1921 he sent a copy to Carter G. Woodson, the Black historian who pioneered African American studies and founded what would become Black History Month. Alderman’s cover letter to Woodson said the booklet still represented the clearest expression of his views 13 years later. He proceeded to recap the more important points, reiterating his long-held views on Black people’s limited potential. The missive was particularly condescending, considering the addressee. Woodson, the son of formerly enslaved parents, held a master’s degree from the University of Chicago and a Harvard Ph.D. Alderman’s formal education terminated in a bachelor’s degree from Chapel Hill.

Problematic legacy

Virginia’s first president is credited with founding the modern University by raising UVA’s prominence in scientific research. He did so, in significant part, by doubling down on the study and teaching of eugenics, the ersatz and disgraced science obsessed with selective human breeding. It’s a broad-spectrum form of prejudice, demeaning African Americans, Jews, Southern Europeans, Asians, immigrants and people with disabilities, essentially anyone other than healthy Anglo-Saxons.

Alderman didn’t introduce the scientific pursuit of eugenics to UVA; it was already well-established here, and not just here but practically everywhere. The theories had captured the interest of the most prestigious universities in the U.S. and Europe, as they soon would Nazi Germany.

As Dorr’s book on Virginia eugenics puts it, “Edwin Alderman was swept along by the surge in scientific racism.” He points to Alderman’s wave of hiring. In 1907 he brought on Harvey E. Jordan, the medical professor who five years later would publish Eugenics: The Rearing of the Human Thoroughbred.

Ivey Foreman Lewis, hired in 1915 to chair the biology department, became one of Alderman’s closest advisers, especially in personnel decisions. Lewis organized faculty support for Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act, which barred interracial marriages. He similarly helped along the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924, which would eventually account for an estimated 8,000 forced sterilizations of people designated as mentally disabled. Throughout the early 20th century, Dorr documents, UVA trained up a generation of scientists, physicians, high school teachers and policymakers in eugenics.

How much of that legacy directly ties to Alderman? Dennis, a history professor at Acadia University in Nova Scotia, considers eugenics and New South progressivism “one and of a piece.” If Alderman is lauded as a New South reformer, “I see no reason why he shouldn’t also be held responsible for the kinds of professors he hired,” Dennis says, “without laying everything at the feet of one individual as if he was solely responsible for promoting those ideas. But they shared a worldview, and he helped build and legitimize that worldview.”

Then and now what?

Suarez describes his committee’s approach to taking the full measure of Edwin Alderman as judicious. “Over time we found that there were a number of aspects of Alderman’s values and decisions that he made that were incommensurate with the values of the University today,” he says.

If not Alderman, then who? That question played in the background throughout the deliberations. In a sense, it preceded them. With a charge broader than simply reviewing requests that cross its desk, the committee from its outset made note of UVA figures deserving of honor in the historic landscape.

In those general discussions and then, later, in those focused on the library, the name Edgar Shannon kept rising to the top. Suarez says the committee undertook a three-step process: It evaluated the appropriateness of continuing the honor for Alderman; it reached an “Aha, yes,” for Shannon; then it set out to vet Shannon with the same rigor it had applied to Alderman.

Briefly, the group flirted with not naming the building for anyone at all but rebranding it Commonwealth Library. Says Suarez, “In the end we decided, ‘Hmm, sort of a little bit anodyne, a little bit not signaling our values enough.’”

Why Shannon

The Shannon proposal took the library conversation in a different direction, one more compatible with a more pluralistic institution. Shannon pushed UVA to integrate. In his first year in office, 1959, he hired Paul Saunier, a key operative in the effort to make the University more attractive to Black candidates. There was much to overcome. A Confederate flag flew on the Corner; fans at football games sang “Dixie” when Virginia scored. UVA had only the previous spring handed out its first undergraduate degree to an African American student.

By 1966, almost midway through Shannon’s presidency, UVA still had only 68 Black students on the rolls, less than 1 percent of the student population of 7,873. By fall of 1974, at the end of Shannon’s final admissions cycle, Black enrollment had grown sevenfold to 479 (3.3 percent) of a total population of 14,382 students.

That larger number, overall enrollment, nearly tripled during Shannon’s 15 years, the consequence of one of his signature accomplishments, full coeducation. It simultaneously increased UVA’s size and selectivity. It was a long time coming, and Shannon moved slowly as he navigated Board resistance. Ultimately it took the ACLU and a federal court order to remove restrictions and accelerate the pace.

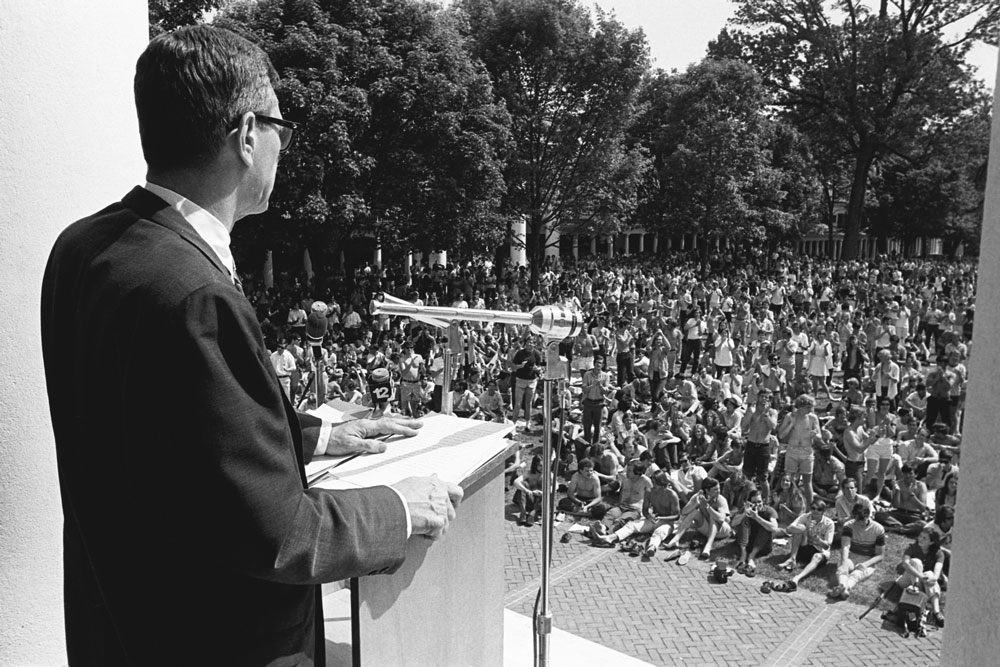

Shannon’s finest hour came during his presidency’s greatest turmoil, the May Days 1970 antiwar protests. In a crescendo moment, after having prevented destruction and fended off student demands, he appeared on the steps of the Rotunda before an estimated crowd of 4,000 to denounce the war. It was a stunning stance for a World War II veteran awarded 11 battle stars, one of them Bronze, who during his career had served on the boards of the U.S. Naval and Air Force academies. Amid subsequent calls for his ouster, the Board stood by him. A few weeks later, as he processed down the Lawn for Final Exercises, a swell of applause built to a prolonged standing ovation.

Alderman’s shining hour was the Woodrow Wilson eulogy, mentioned in all his obituaries for its flights of oratory. Shannon’s Rotunda statement is remembered instead for the courage of its convictions. The most sympathetic view of Alderman seeks to understand him as a product of his times. Shannon’s admirers point to his having the fortitude to challenge his times.

Another contrast, for purposes of whose name to associate with UVA’s principal humanities library: Shannon was a scholar, immersed in the humanities as an authority on Alfred, Lord Tennyson. John T. Casteen III (Col ’65, Grad ’66, ’70), UVA’s seventh president, who earned his degrees during the Shannon years, remembers seeing the president head inside Alderman Library most afternoons at a predictable hour. Unusual even then, Shannon conducted classes and scholarly research while in office. Says Casteen, “I can remember people who would complain that he was spending time with his students and with Tennyson while also being the president.”

Avoiding taking a side on the library’s name, Casteen says of Shannon: “He drove the University toward academic excellence, which had not been a major consideration previously. He made the library the center of the University’s intellectual life. He took the University to distinctions that simply weren’t out there before his time. And he was a very active, central part of the University.”

If UVA had just built a new library with no preexisting name, should it be named for Shannon?

“Yeah, I think that’s an easy answer,” he says.

Moving forward

Suarez says he has not compiled a timeline of when his committee reached its consensus to recommend renaming the library for Shannon. Sarita Mehta (Col ’22), a student leader on the committee who stayed on after graduation, pegs it to around April 2022, with a draft proposal submitted that August, based on her review of emails.

The formal version for the Board of Visitors’ consideration was tendered in May 2023. It didn’t make the agendas for the subsequent two regular meetings and then got tabled from a third, in December, setting up the anticipated March vote.

For all the committee’s 20 months of extensive research and deliberations, it kept its recommendation to a spare 529 words. It noted that Alderman “brought the University into the first half of the 20th century and was principally responsible for giving the University the organization and ethos by which it then operated.”

Using parallel construction to draw a distinction, it continues: “Similarly, it was president Edgar Shannon who ushered the University into the second half of that century and whose leadership largely gave our University the character, values, and aspirations by which we understand the University of Virginia and its commitments to excellence today.”

Says Suarez, “Alderman’s career is a matter of public record, but we thought that this should be an affirmational document.”

That suits Unsworth, the University librarian who called the question in 2021. He says, “My goal is to see the building renamed, not to score points on the dead.”

Whatever the Board vote, Unsworth and naming committee members envision some form of library exhibit to give a fuller history of Alderman, explain why the University chose him for the honor in 1938 and, if applicable, why it felt compelled to find a replacement, and why Shannon.

Change or no, the renovated space will likely need to offer context for the message on the wall that faces visitors as they step inside Memorial Hall, the library’s grand foyer. Beneath a giant clock, etched into the stonework in gold, it says: “THIS BUILDING ERECTED IN MEMORY OF EDWIN ANDERSON ALDERMAN FIRST PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 1904 – 1931.

Says Unsworth, “I don’t see that going away.”