Integrating from Behind the Scenes

The legacy of Paul Saunier, a deft hand in turbulent times

When the University of Virginia intensified efforts to recruit African-American students in 1969, it didn’t hold back. Nor did it hide the sentiments of the few black students already enrolled.

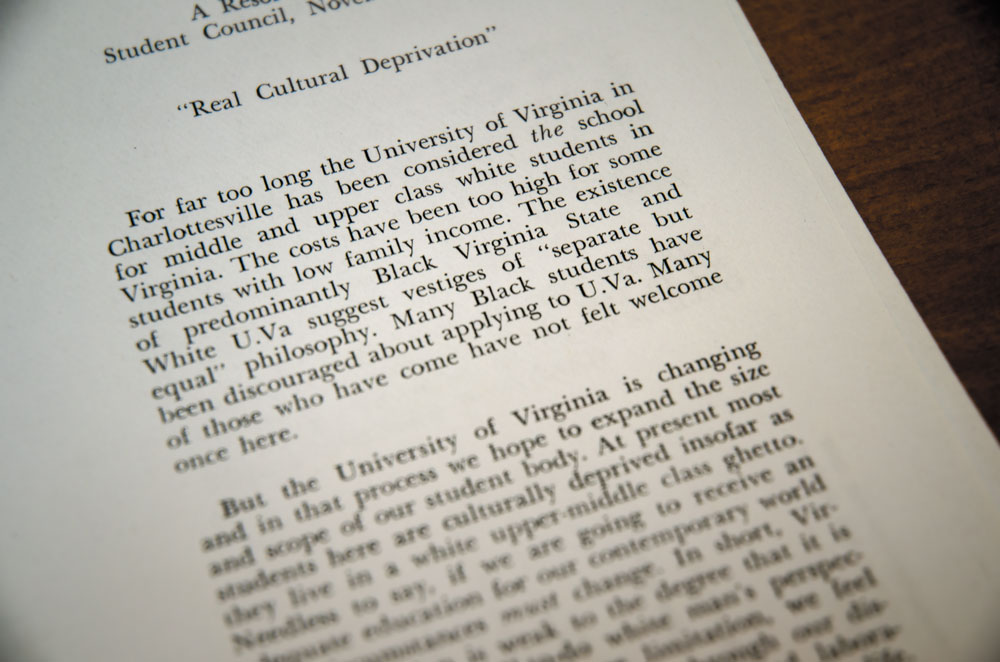

The Admissions Office distributed a pamphlet in which the Black Students for Freedom described the University as a “plantation school,” cited Malcolm X’s condemnation of “the American system of exploitation and oppression,” and counseled against enrolling simply “to foster integration for the sake of integration” or “to absorb or be absorbed by ‘White Culture.’” They exhorted potential applicants to a higher purpose: “The University of Virginia will be more meaningful to Black people—in fact, all people—if the Black students make it so.”

The unfiltered approach—asking black students to speak frankly to black students—was advanced especially by administrator Paul Saunier, the politically astute former journalist, campaign publicist and congressional aide charged with helping to integrate UVA. In an era better known for intransigence and strife, Saunier shrewdly favored consultation over confrontation, engagement over enforcement, straight talk over lip service.

Saunier (pronounced SAWN-yer) died in February at age 97. He was remembered as an instrumental but mostly behind-the-scenes member of the group of administrators led by President Edgar Shannon who were determined to change the University from a nearly all-white and nearly all-male institution. Shannon hired Saunier in 1960, barely a year into his presidency.

“Paul was involved in the discussion at the top level as to what needed to be accomplished,” says Ernest Ern, another of those administrators. Ern was dean of admission and later vice president for student affairs and senior vice president. “It was more than obvious that we had to recruit.”

It was slow going. African-American students from the late ’60s recall Confederate flags flying at a restaurant on the Corner, though at least by then the “whites only” signs had come down at the eateries. At football games, they recall, fans still sang “Dixie” after every Cavalier score. Graduate programs and professional schools consistently had a few black students in those years, but College enrollment had gone from zero in 1960 to just enough to be counted on one hand by 1969.

“The environment was pretty hostile, and it was clear that we weren’t welcome,” says John Charles Thomas (College ’72, Law ’75), who came to UVA in 1968. “I think we started with six, and three of those left as soon as they saw those Confederate flags and ‘Dixie’ and all that.”

“It was not a welcoming environment by any sense,” agrees Ern. “Yet the students who came in began to get involved in the life of the University.”

Thomas, who in 1983 became the first African-American justice of the Virginia Supreme Court, recalls how Shannon included him in a student leadership retreat when he was president of the Black Students for Freedom in his second year at UVA. He was one of the writers of that “plantation school” pamphlet and became a recruiter himself, driving in a state-owned Dodge sedan to meet guidance counselors and speak to promising black students at high schools in Tidewater, his home region.

“We’d say, ‘This is your university, too. Your state taxes paid for this,’ ” Thomas recalls. It was a different message from what he had been given by his own guidance counselors at a mostly white high school in Norfolk: “They advised me not to go to UVA,” he says. “They said I wouldn’t be comfortable there.”

Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had outlawed dual systems of higher education, Virginia’s system remained very dual five years later. According to statistics compiled for the Lemon Project, an examination of the College of William & Mary’s role in slavery and racial discrimination, only 209 black students were enrolled in Virginia’s white four-year colleges in 1968-69, out of a total enrollment of about 44,000. Of the 6,179 students enrolled at the state’s two black colleges, 50 were white.

Keeping African-American students out of white colleges was a prime component of the Virginia culture that historian J. Douglas Smith addressed in his book Managing White Supremacy. The crooked yardstick of “separate but equal” was applied to public schools and colleges in Virginia and the rest of the South for much of the 20th century. Under the dual system of education, black high school students who wanted to pursue college were steered to the black state colleges, such as Virginia State in Petersburg—on the “separate but equal” argument that they could pursue any degree there that a white student could pursue at the University, at William & Mary or at any of the other white state schools.

As preludes to what Ern calls the “unwelcomeness” that greeted the few black students enrolled at the University in the 1960s, consider the University’s central role in two earlier episodes.

In 1935, Alice Jackson, a graduate of all-black Virginia Union and a graduate student at Smith College, applied to the University to seek a master’s degree in French. The Board of Visitors denied her admission, asserting that “The education of white and colored persons in the same schools is contrary to the long established and fixed policy of the Commonwealth.” As a lawsuit brewed, the state hustled to add a graduate school at Virginia State to maintain the “separate but equal” claim. And in the next General Assembly session, in 1936, the legislators appropriated funds and authorized the University and other whites-only state colleges to provide “scholarships” to black applicants who would then pursue their education out of state. Regularly replenished by the legislature, that pot of money paid qualified African-American scholars to leave Virginia for decades, and it kept the color line in place.

In 1950, a federal court compelled the law school to admit Gregory Swanson, over the objections of the Board of Visitors, which cited the state law against integration and the “tradition” of paying black students to go out of state. Swanson’s matriculation is marked historically as the integration of the University, and it legally ended the scholarship ploy. But it also illustrates the hostility that faced African Americans at the University for years to come: Ostracized and isolated on Grounds, Swanson left after one year.

UVA’s graduate and professional schools regularly enrolled a few African-American students and women from that time on, but their undergraduate enrollment remained stymied.

Wesley Harris (Engr ’64) enrolled in the Engineering School in 1960, the year Saunier left a position as chief aide to Richmond’s congressman to become assistant to Shannon. “It certainly, to me, was a very hostile environment,” he told a Virginia Magazine video interviewer in 2011. “Lit cigarettes were thrown at me from moving cars.” Now a professor at MIT, Harris recalled that he was spit at, and his assigned roommate, a white student, refused to room with him. In local theaters—as Virginia’s Jim Crow laws required at that time—blacks and whites were restricted to separate seating areas. “On the Corner,” Harris recalled, “the only restaurant that would serve us was the University Cafeteria.”

Breaking down “whites-only” policies on the Corner became one of Saunier’s early targets. In an interview with the Office of University Communications in 2014, Saunier, then 95, said he and a community activist told restaurant owners that a black student they refused to serve might turn out to be an international student who was a prince, and that they were risking an avalanche of bad national and even international publicity.

Saunier’s papers in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library provide a further glimpse into his behind-the-scenes work, such as memos from David Yu, the religion professor assigned to work with community leaders to pressure businesses on the Corner not to discriminate. In a March 1964 note, Yu reports that the Virginian restaurant has expressly said “that it would not serve Negroes.” In a note two weeks later, Saunier discloses that he has met with faculty members who were close to a student group planning to picket on the Corner, and a “mutually beneficial” exchange of information presumably forestalled the protest. He applauds Yu for his discussions with the owner of the restaurant, who has changed the policy. But the process is slow. Nearly six months pass before Yu reports that the last restaurant that refused to serve blacks—George’s—has come around, and all the businesses are open to all customers.

In 1966, the federal government began to require states and institutions to keep employment, enrollment and other statistics by race and sex, the better to enforce civil rights laws. Saunier was reassigned in 1967 to focus specifically on equal opportunity issues, and it fell to him to push that record-keeping practice through the friction-filled channels of the University’s academic and administrative departments. The demands in his correspondence with the deans of the schools, the hospital and others are masked by courtesy, deference and understanding, but there’s no doubt that arms are being twisted. He insists with authority that they alter their existing forms, institute the changes and provide the necessary information.

Ern agrees that Saunier’s style of diplomacy came with determination about results and a firm hand. “Once he locked into a belief, he didn’t let go,” Ern says. “His belief was that UVA was going to be a better place because of the results of the efforts to diversify our student body.”

Saunier’s commitment to change also applied to the barriers to admission and success at UVA that faced women, Ern says.

Saunier was not on the faculty task force that in 1968 recommended admitting women as undergraduates or on the committee that sorted out the ways and means after the Board of Visitors accepted that recommendation in 1969. But he applied his deft political hand behind the scenes, advising Shannon in detail how certain sections of the committee’s report could be reworded to minimize the “misunderstanding and pain” of opponents of coeducation among alumni, students, the public and the General Assembly—while remaining true to the committee’s intentions.

The eventual enrollment of female undergraduates followed a path similar to that of African Americans, resisted by an old guard but spurred by demand for opportunity, changing expectations in society, and lawsuits. Actions by the Shannon administration, as well as actions in court, were dismantling Virginia’s dual system, under which Mary Washington College in Fredericksburg was women’s “separate but equal” alternative to UVA. Enrolled by court order, Virginia “Ginger” Scott (Col ’73) was the lone first-year woman in September 1969. As the University’s changes in policy caught up and took hold, several hundred more women enrolled for classes in 1970, and the number rose steadily in the years that followed.

For African Americans at that time, the recruiting effort seemed to be helping.

“Our good fortune was that we focused on a given number of guidance counselors who happened to be black, and they were the ones who helped turn the tide,” says Ern.

For a taped interview in 1975, Ern, who was then vice president for student affairs, compiled application statistics for the College of Arts and Sciences. Before 1967, there were never more than a dozen black applicants. Of the 12 who applied in 1967, three or four enrolled. But with the addition of the first black Admissions officer that year and the recruiting campaign at black high schools in full swing, Ern said, applications began to grow: 30 in 1968, 90 in 1969, 175 in 1970, 250 in 1971. The “yield,” as Admissions jargon puts it, was about one out of four. By 1971, he said, about 90 African-American students were enrolled, and the numbers steadied at that plateau through the time of the interview.

Undergraduate enrollment then was a little more than 5,000, but growing under state pressure, with 3,000 or so more in the graduate and professional schools.

“We were few and far between,” says Willie Ivey (Col ’73), who was John Charles Thomas’ roommate in 1969 and who also recruited black students on behalf of the University back in his home region of Newport News and Hampton. “We worked hard to generate a sense of community. Even if you were excluded from the broader community, there was always somebody you could turn to. If you figured out how something worked, like who was a ‘dyed-in-the-wool, don’t-want-you-here’ professor, it was your responsibility to pass it on.”

Ivey, who is now retired from a career as a computer network expert, sees the work to bring more black students to the University—and to help them succeed—as a network of outreach and support. It took them all: University administrators, professors, African Americans in Charlottesville, high school counselors, enrolled black students.

Thomas agrees: “It’s hardly ever just one person.”

Ernie Gates is a writer and editor based in Williamsburg, Virginia.