Not Without a Fight

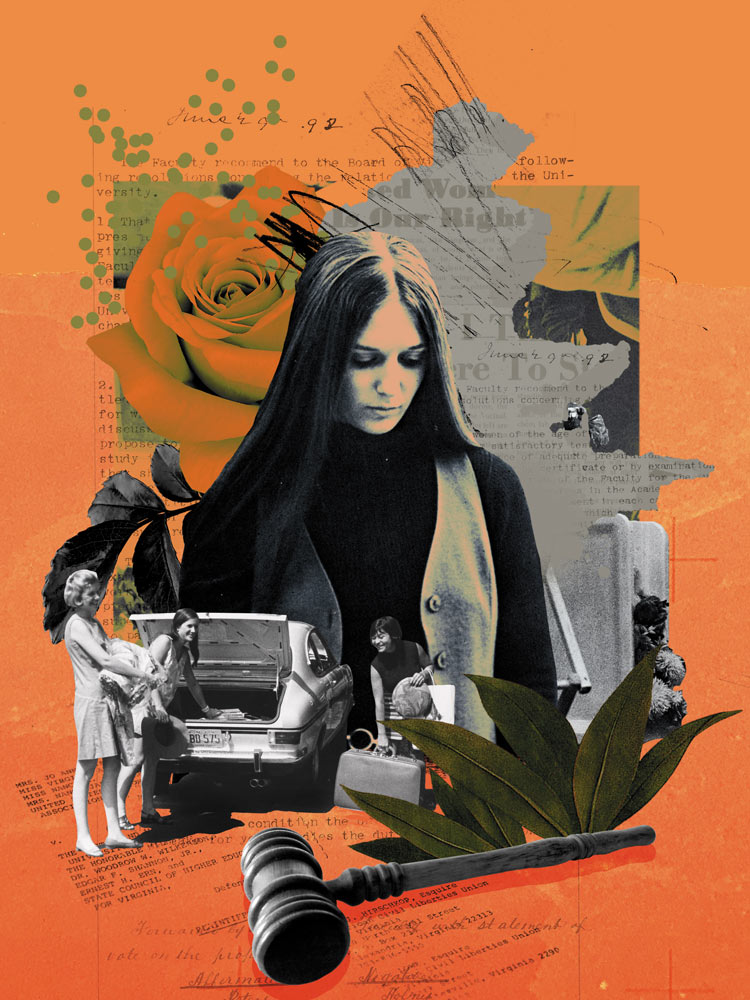

How UVA granted women full admission sooner rather than basically never

Virginia Anne “Ginger” Scott (Col ’73, Grad ’80, Educ ’89) showed extraordinary self-possession at 19. Maybe it was her nature. Maybe it was her circumstances. After her mother died, she dropped out of the College of William & Mary halfway through her first semester. She returned home to Charlottesville, where she lived on her own and found work at a local law firm.

In the spring of 1969, ready to resume her education, Scott scheduled an admissions interview with the University of Virginia. She met all UVA’s entrance requirements, save one: a Y chromosome.

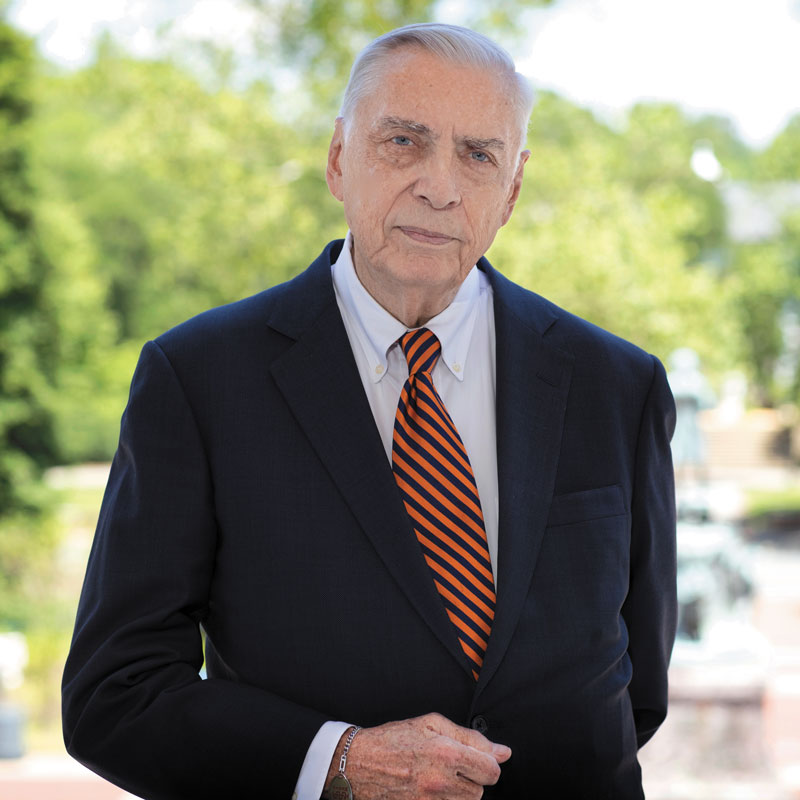

The College of Arts & Sciences was still men only, with limited exceptions for third- and fourth-years. Ernest H. Ern, then the dean of admissions, took the appointment with her anyway on a Saturday morning that March. To this day, Scott, 70, says she doesn’t know why.

Ern, 87, says he wanted to be polite, and indeed, according to the handwritten interview form he completed, he offered her other options, including taking continuing education courses. Those same notes reflect that Scott offered Ern some options: He could let her apply to UVA, or the American Civil Liberties Union would sue him for sex discrimination.

Ern’s comment at the bottom of the form: “must have something on the ball to be accepted to W&M.”

It was an astute observation. Exactly 60 days later, May 29, 1969, Scott’s boss, John C. Lowe (Law ’67), sued the University in federal court in Richmond. He lined up three women to join Scott as parties in the case, each of them prohibited from admission or transfer to UVA based on gender. It was a class action, seeking to represent the interests of all women UVA was barring from applying simply for being women. Lowe sued under the auspices of the ACLU, which paired him with civil rights lawyer Philip J. Hirschkop as co-counsel.

Making good on Scott’s promise, the ACLU lawyers named Ern as one of the defendants.

Notorious before RBG

In the swift course of four months, that lawsuit would bring about the most profound change to UVA going back to the early 20th century and arguably well into the 19th. Full coeducation would open the way for Virginia to achieve the growth it needed to contend as a premier national university, doing so in a way that made it more selective, not less. Academically and socially, UVA grew, and it grew up.

Kirstein v. Rector and Visitors of University of Virginia brought together a celebrated cast from a turbulent era. Lowe, a sole practitioner just two years out of UVA law school, would go on to a career of high-profile cases—defending an American Indian Movement leader in the infamous siege of Wounded Knee, South Dakota; representing accused Vietnam deserter Robert Garwood; and winning an abortion-related First Amendment case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

His more experienced co-counsel Hirschkop had already achieved renown as a civil rights lawyer, including as a member of the legal team in Loving v. Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court landmark that just a few years earlier had invalidated state laws against interracial marriage.

Kate Millett, Lowe and Hirschkop’s star witness in the UVA case, would the following year publish her groundbreaking feminist bestseller Sexual Politics. Time magazine put her on its cover for it.

U.S. District Judge Robert R. Merhige Jr. (Law ’82) rode point on the special three-judge panel that presided over the case. By the following year he would become, according to his Washington Post obituary, “the most hated man in Richmond” for forcing the school systems to integrate; among other aggressions, segregationists shot his dog.

A look back at the UVA case on its 50th anniversary affords the opportunity to fill in a never-fully-told backstory and, perhaps, to undo a few misconceptions. For starters, not everyone in the University establishment opposed coeducation. The mostly conservative faculty almost unanimously supported admitting women as undergraduates. President Edgar F. Shannon Jr. favored it, even if for reasons of temperament or internal political tensions he didn’t seem in a hurry.

Second, from a legal perspective, UVA wasn’t entirely behind the times. Sure, every other public university had gone coed by 1969, not counting the military academies. So had even Princeton and Yale. Yet the legal precedents still hadn’t caught up, which left the University some ground on which to mount a defense.

“This was the first case of its kind,” says UVA law professor Anne M. Coughlin, an expert in feminist jurisprudence. “This is Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” she says, underscoring how the legal issues predated by several years the U.S. Supreme Court justice’s early work as a women’s rights advocate, what would come to be known as “the equal protection revolution.”

The record also puts the lie to a counternarrative of the time, one preserved in Virginius Dabney’s (Col 1920, Grad 1921) 1981 one-volume history of the University, that UVA was well on its way to coeducation—the Board of Visitors had nominally approved it—and that the ACLU suit amounted to meddlesome grandstanding. A Roanoke World-News editorial called the complaint “a bit silly.” The Lynchburg News editorial page derided it as “pushy” simply because the “‘liberal’ ACLU” was involved. In fact, the record makes plain that what Scott, her fellow plaintiffs and their legal team accomplished in the fall of 1969 wouldn’t have happened even in 10 years had they left the University to the devices of its own coeducation plan.

God Speaks

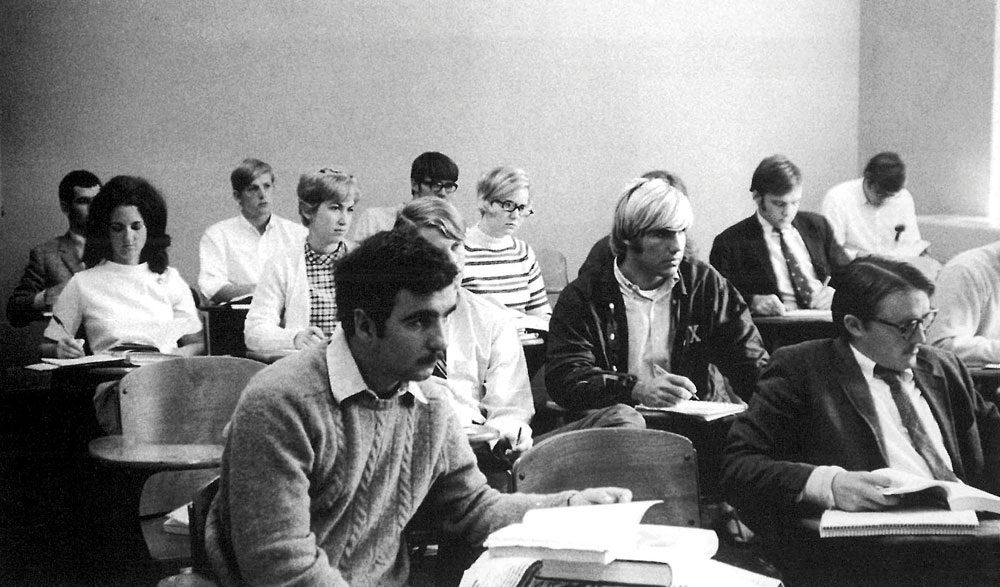

More than two years before the litigation, President Shannon sought the Board of Visitors’ blessing to explore full coeducation for the College, something the graduate and professional schools had allowed since 1920. The board greenlighted a study of whether to allow female undergraduates or, as its resolution put it, “whether there is a need.”

From that initiative came the Woody Report, taking its name from committee chairman and French language professor T. Braxton Woody (Col 1923). Though not the first choice for the assignment—he took over for a colleague who had had a heart attack—he was a dyed-in-the-herringbone-tweed traditionalist. An alumnus and longtime faculty member, he had become the Honor System’s voice of God. His booming baritone during first-year Honor orientations famously terrified generations of Wahoos about the perils of lying, cheating

or stealing.

His bona fides made all the more damning the unequivocal recommendations that came from the Woody Commission’s 74-page report: The University needed to grant women full admission without further delay. Separate sections made the case for women in the interests of fundamental equality, UVA’s academic stature and developing a healthier cultural climate. The study included the view of the faculty: 90 percent in favor of coeducation vs. 6 percent against among 157 polled. And, after duly noting the counterarguments, the Woody Report explained why none overrode the advantages of coeducation.

A section on the legal implications of barring women read like a roadmap for a court challenge: “Perhaps we are not yet legally obligated to admit women, but is it morally right, is it defensible in the name of justice, to discriminate against them on grounds of sex?”

It presented hypothetical examples of unfairness, which may well have informed the clients Lowe lined up for the court challenge. First there was the theoretical example of an otherwise qualified local Charlottesville woman who was expected to enroll at Mary Washington College, a former teachers college brought under UVA control in 1944 to suffice as a sister school. Making a qualified candidate go to Mary Washington, 70 miles’ drive away in Fredericksburg, when she had UVA in her own backyard, was an inconvenience and a comedown, the report said. Scott, a graduate of local Albemarle High School, neatly fit the fact pattern.

The report raised the dilemma that wives of UVA students faced, having to choose between their marriages and their education—staying in Charlottesville or leaving home to find school in some other place. Those were the circumstances of plaintiffs Jo Ann Kirstein, 19, married to a UVA law student, and Nancy Jaffe, a 26-year-old registered nurse whose husband was a medical intern at the UVA hospital. (The fourth named plaintiff, Nancy Anderson, 25, wanted to transfer into the College from the Nursing School, which the rules also barred.)

Hirschkop, 84, Lowe’s co-counsel, says Dean of Women Mary E. Whitney helped the legal team recruit Kirstein, Jaffe and Anderson to the cause, and she continued to help the lawyers behind the scenes before resigning from her post. “She’s the hidden hero of the whole case,” he says.

In less than a year, the Woody Report would come to be known as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 7 and would later achieve the immortality of official citation in the federal court’s final pronouncements in the case.

The Board Gives, It Takes Away

Woody’s booming call for coeducation moved the ball only so far. When the Board of Visitors approved Shannon’s original proposal to study coeducation, it provided for a two-step approach. First a committee would have to establish the need. Then Shannon would need to enlist a second group to assess the feasibility.

That job fell to then-Provost Frank L. Hereford Jr. (Col ’43, Grad ’47), a Louisiana-born gentleman of the University. He was a no-nonsense nuclear physicist and nobody’s idea of a progressive. In the 1970s, after he succeeded Shannon as University president, he resisted nearly yearlong criticism of his membership in then-whites-only Farmington Country Club, maintaining that he was working for change from within. When the club’s board voted overwhelmingly to reaffirm the racial barrier, he resigned along with other prominent local officials. Several years after that, amid increasing hostility with the Cavalier Daily over its independence, he evicted the student newspaper from its offices on Grounds. Students hanged Hereford in effigy from a tree, according to his Washington Post obituary.

Hereford’s committee didn’t attempt to block women from coming to the College—the momentum of the times and the moves of peer institutions made coeducation unstoppable. Instead, it sought to control the influx and influence of women in undergraduate life. The rationale was preserving UVA’s unique character.

True to style, Hereford moved efficiently. He got the assignment Dec. 31, 1968, turned in preliminary recommendations exactly one month later, and secured board approval for them 15 days after that, at the Board of Visitors’ Feb. 15, 1969, meeting.

The Hereford plan, as adopted by the board, took a multipart approach. First the board repealed the long-standing restrictions on admitting women to the College, a move it would ballyhoo throughout the court fight, still more than three months away, as mooting the case in its entirety. UVA would argue: You can’t sue us to coeducate; we already did, on Feb. 15—everything else is just quibbling over the details.

But, as would play out, the detriment was in the details. Simultaneous to removing restrictions to women’s College enrollment, the board added new ones. Among the provisions, women were to be added to the male population over time, not displace current levels of male enrollment. In essence, women were not to compete with men for admission. More explicitly, during an unspecified “initial transition,” the board insisted, “The number of qualified male applicants admitted should not be curtailed as a result of the admission of women.”

The board directed that any coeducation plan take care not to hurt enrollment at the state’s public women’s colleges, namely Mary Washington, over which it had corporate responsibility. That meant UVA wasn’t to accept too many qualified women, even if it had room for them, but rather push them to choose the sister school.

Over the next several months, including after the filing of suit that May, the Hereford plan, and its enrollment models, would undergo continual refinement, but the gist remained the same. Using his board-approved preconditions, Hereford projected that by 1980, the end of a 10-year phase-in, women would represent 35 percent of College enrollment and 29 percent of the University’s.

It was a complicated construct, one not easily explained, as Hereford would painfully discover the following fall while sitting in a federal witness box.

The Lawyers Prepare

As University officials incubated their coeducation plans during the first few months of 1969, the idea for a court challenge was about to hatch. Ginger Scott walked into the law offices of John Lowe looking for a job.

“I tried not to sound desperate as I explained my mother’s recent death and immediate need for employment,” Scott writes in a draft history she shared with Virginia Magazine. “I sensed that he understood my situation.”

She told Lowe she would want to go back to college. Lowe mentioned UVA, and Scott had to explain that it didn’t accept women.

In a 2017 interview with University news associate Jane Kelly just weeks before his death, Lowe recalled his reaction: “You’ve got to be kidding me!” He had female classmates at UVA Law but had done his undergraduate work at Lehigh University, not knowing about UVA’s single-sex College. He told Scott, “Well, then, we’ll just have to take care of that.”

Scott writes she wasn’t sure what he meant, but she got the job, started that week, and was grateful. By mid-March, Lowe got the ACLU of Virginia to support his cause. At that point, Scott writes, “John asked me if I wanted to be a plaintiff in the suit and I agreed.”

One of her first tasks was to schedule that admissions interview with Ern. Lowe didn’t coach her for the encounter, she told Virginia Magazine in a brief interview: “John was the kind of person who would have said … just go in and tell the truth.”

As Ern’s notes make clear, she got her point across, which in turn helped Lowe establish a record. He similarly collected evidence of UVA’s refusing to consider his other clients, including Ern’s rejection letter to Kirstein.

That May, once he and Hirschkop filed the case in Richmond, Lowe let Scott do the honors of personally serving her own suit on the University muckety-mucks. She enlisted the help of high school friend Sally Floyd, home for the summer from her freshman year at the University of Michigan.

Home in Floyd’s case was Pavilion II, the residence of mathematician and then-dean of the faculty of Arts & Sciences Edwin E. Floyd (Grad ’48), just down the east colonnade from the University’s executive offices in Pavilion VIII. Together, according to Scott’s manuscript, they strolled the Lawn hand-delivering summonses and complaints to the offices, if not the individuals themselves, of Shannon, a named defendant; Weldon Cooper, the secretary to the defendant rector and Board of Visitors; and UVA’s in-house legal adviser, Leigh B. Middleditch Jr. (Col ’51, Law ’57).

Another perk of Scott’s job—secretary’s assistant was her title—was summer reading. It came in the form of the unfolding pretrial testimony as fresh deposition transcripts arrived from the court reporter that August. She read them in between answering the phones.

Like Lowe’s pretrial cross-examination of lead defendant Frank W. Rogers (Col 1909, Law 1914), the rector of the Board of Visitors. She pored over her boss’s coaxing Rogers to elaborate on the burdensome business of converting dormitories to accommodate women. The rector started talking about the need to equip them with laundry facilities and, of all things, ironing boards. Rogers said, “When you get into those things you are just overcome with the detail you get into,” Scott records in her manuscript, no less incredulous 50 years later.

The Rector Digs In

Middleditch, now 90, the University’s in-house counsel at the time, points to Rogers as the reason UVA fought the challenge tooth and talon. “He was a tough bird, and he did not want to be pushed around by anybody,” Middleditch says. “He just put in his heels.”

Born in 1892, Rogers was a World War I fighter pilot and a well-established lawyer undaunted by playing a weak hand. In 1960 he was part of the legal team that went to the Soviet Union in a failed attempt to win clemency for Gary Powers, the U-2 spy plane pilot whose capture triggered a Cold War crisis, according to a Virginia Business tribute to the Roanoke law firm Rogers founded.

Shortly after the board’s Feb. 15 vote to open the College to women, Rogers, who supported the resolution, wrote a disappointed alumnus to say, “I see nothing good in coeducation at the University.”

The University had two fundamental disadvantages in the case: the less-compelling fairness argument and a less-than-favorable venue in which to make it. Lowe and Hirschkop chose to sue in Richmond, not Charlottesville—the federal Eastern District of Virginia, not the Western—for good reason, and they won the procedural fight to stay there. Not for nothing had they locked in Gov. Mills E. Godwin (Law ’40) and other Richmond-based state authorities as defendants. Richmond deprived UVA of any home-court advantage. More important, it ensured that the case went in front of Judge Merhige, the Eastern District’s resident judge for Richmond and a sympathetic ear Hirschkop knew from his previous civil rights work.

Once the matter came before Merhige, the case moved fast, as was the reputation of the Eastern District. In early September, he sided with the ACLU and ordered UVA to let Scott enroll in the College that fall. It was a temporary injunction, a stopgap that spared her from delaying her education another year while the case continued. If she lost her court challenge, the injunction would dissolve, and she’d have to drop out of school again. That risk, and the possibility of not getting their tuition refunded, dissuaded the other women in the case from enrolling that fall, according to Scott.

“I decided to risk it,” Scott writes, confident her ACLU lawyers would prevail.

Merhige’s ruling gave her good reason to think so. It took as undisputed fact that UVA was discriminating purely on the basis of gender. And the judge signaled he would be ready, when the time came, to declare UVA’s admissions policy unconstitutional. Merhige wrote, “where the facts and the law appear exceptionally clear in favor of the [challengers] … the court should not hesitate to act.”

The Judges Push

It was just a preliminary ruling in the case, but it didn’t bode well for the University. The main event was three weeks away, at the end of September, the hearing to determine whether to make the order opening College admissions to women permanent and more far-reaching. This was a class action, after all, brought on behalf of all women everywhere who would want to apply to the College.

That proceeding was scheduled before the case’s three-judge panel, Merhige plus U.S. District Judge John Ashton MacKenzie, considered a conservative, and U.S. Fourth Circuit Judge J. Braxton Craven Jr., considered just plain difficult, at least by ACLU lawyer Hirschkop. Regardless of how they aligned along an ideological spectrum, the judges were unanimous in one respect: They wanted the parties to settle.

It’s understandable. The two sides had given the judges a stark choice to make in a roiling and unsettled area of law, women’s rights under the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, that revolution a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg had yet to wage. Lowe and Hirschkop were pushing for the court to treat gender discrimination with the same disfavor as race discrimination, the more developed body of equal rights law. There the courts apply what’s called “strict scrutiny,” maximal skepticism to any governmental attempt to treat people of different races differently. As a rule, no policy can withstand that intensity of judicial review.

UVA protested that no court had made that leap from race to gender. It argued for a more forgiving standard of review, called “rational basis,” used for cases far removed from those involving race, where all a governmental entity need do is show a plausible reason for treating different groups differently, in this case female applicants versus male. If the court would use that lower bar, then UVA could have some breathing room to talk about preserving the character of the institution, why Mary Washington was a good-enough alternative for women and all the reasons coeducation would take years to accomplish.

During the 1970s, a new legal standard would develop for use in gender discrimination cases, called “intermediate scrutiny,” something a little less demanding than strict scrutiny but a good deal tougher than rational basis. Without benefit of it in 1969, however, the judges in Richmond endeavored to find a third way of their own. The morning of the hearing they ordered the parties into chambers and leaned on them to reach consent, according to a summary of the case Hirschkop compiled several years ago.

Hirschkop would have none of it. He didn’t see that UVA offered anything reasonable, he wrote. That left the judges little choice but to go through with the hearing that afternoon. They gave the parties barely more than two hours for it, and Craven made sure to keep things moving.

The Witness Mocks

Lowe made the most of the time allowed and of his expert witness, feminist Kate Millett. The year before, Millett had completed an extensive study showing the educational inequities between the Seven Sisters schools and their Ivy League brothers. When Millett put UVA and Mary Washington in that context, she called the disparities “appalling,” according to the transcript. “Mary Washington I found to be deplorable and in no way comparable. I found this to be true of every department we examined.”

Lowe raised UVA’s concern about the burden of retrofitting restrooms for women.

“Well, perhaps they could plant flowers in the urinals,” she answered, the transcript not doing justice to her clipped manner of speaking, acquired from her years of study at Oxford, Hirschkop says.

The bench erupted in laughter, remembers Middleditch, who as the University’s in-house counsel was a backbencher during the proceedings.

Lowe recalled for Millett deposition testimony that women on Grounds would require the University to purchase “diminutive furniture.”

Lowe: Would you comment on that?

Millett: Is it worthy of comment?

Lowe: I think the Court would be interested in hearing what your opinion is.

Millett: Diminutive furnishings like in kindergarten, perhaps?

Ern, the admissions dean, also remembers sitting through her testimony. “Talk about a hurricane,” he says.

The Provost Flops

James Harry Michael Jr. (Col ’40, Law ’42), a state senator destined for the federal bench, led the defense. A year earlier, Lowe had been his young associate. Throughout the case, the two opposing counsel continued to work out of their respective law offices in the same converted house, Lowe upstairs, Michael on the main floor, a block off Charlottesville’s historic Court Square.

Michael put up just one witness: Hereford. As the provost recited the various rationales and conditions baked into his plan, Judge Craven pointedly interrupted.

Hereford: Now we have been able to maintain consistently at the University a policy whereby all qualified Virginians who apply for admission are admitted.

Craven: Male?

Hereford: Sir?

Craven: Males, of course?

Hereford: Yes, male. I am sorry. Excuse me. All qualified male applicants.

It got worse when Lowe took the witness on cross-examination—and took him by surprise.

Nine days before the hearing, Kevin L. Mannix (Col ’71, Law ’74), then the vice president of student council and the token undergraduate on a coeducation subcommittee Hereford had created, handed the provost his self-styled “Minority Report.” Its cogent four pages eviscerated the Hereford plan as a discriminatory quota system—“limiting the enrollment of women … while protecting the enrollment of men.” In his UVA Today interview Lowe said Mannix had called him at 10 p.m. the night before the hearing to tip him off about the report and deliver a copy.

“Are you familiar with this document?” Lowe asked Hereford at the hearing. Yes, the witness answered. Had he included the minority report with the full report, the one the defense had presented to the court?

The court reporter recorded Hereford’s answer as “(No response.)”

Lowe entered it into evidence himself, and continued: “Was it your intention not to submit this to the board, this minority report?”

Hereford gave a flustered response, but at that point it didn’t matter. The court went into recess.

The Board Flips

The panel ruled the next day, with Craven, its ranking member, writing the order. It seemed to reflect the previous morning’s settlement talks more than the afternoon’s testimony. The order avoided setting a precedent by instead leaning on UVA to fix things, making a point to praise the Woody Report. If forced to choose, Craven said the court would apply the fatal test of strict scrutiny to UVA’s admissions policy, invalidating gender-based school segregation at UVA the same way the U.S. Supreme Court rejected race-based school segregation in the 1954 landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. But rather than go there, Craven said the court had every confidence the Board of Visitors would do the right thing at its next meeting, which he noted was scheduled in three days, Oct. 3. He directed the University to obtain Judge Merhige’s approval of a coeducation plan within a month.

The ruling made permanent the earlier injunction that let Scott start at UVA that fall. Now she could finish there too, clearing the way for her to earn her undergraduate degree in 1973, a full year’s bragging rights ahead of the women of the Class of 1974, celebrated as the first wave of College coeducation.

Sure enough, on Oct. 3, 1969, the board scrapped the Hereford plan, officially acknowledged Mannix’s minority report and approved a two-year phase-in of female undergraduates, beginning in the fall of 1970—with full and unrestricted coeducation taking effect by fall 1972.

When it did, Mary Washington broke free of UVA and has gone on to become a full-fledged university of its own.

At a follow-up hearing in December, Lowe and Hirschkop tried to get the court to rule more broadly—in favor of the entire class of women they sought to represent, not just the four named plaintiffs; to apply Brown and strict scrutiny to all vestiges of single-sex higher education in Virginia, not just UVA; and to award them damages. Craven, again writing for the court, said no, no and no in the case’s final ruling, cited as Kirstein, 309 F. Supp. 184 (E.D. Va. 1970), even though Scott was the only one of the four women to enroll. The opinion again cited the Woody Report and praised UVA for its good faith and openness to change, leaving unspoken that it took the ACLU to bring it to the brink.

The courtroom and boardroom dramas ended, it fell to Vice President of Student Affairs D. Alan Williams to make happen in two years what the University insisted in court couldn’t be fully accomplished in 10. He led a blue-ribbon team tasked with coordinating the preparations for women to join the College on equal footing with men. Looking back on the assignment at age 92, Williams confides that instituting coeducation really wasn’t that complicated.

“The court order didn’t say you get to fool around for 20 years,” he says. “You just had to go at it. That’s all there was to it.”