The Mystery of Brooks Hall

The hidden stories behind one of UVA’s most unusual places

Brooks Hall, the pressed brick, Beaux-Arts style building just east of the Rotunda, the one with the names and animal heads carved into its façade, looks peculiar when compared with the Jeffersonian-style buildings on Grounds. According to legend, Brooks Hall looks so different because the architect accidentally sent to UVA plans meant for Harvard, Yale or Princeton. But it turns out that the truth about Brooks Hall is more compelling than the myth.

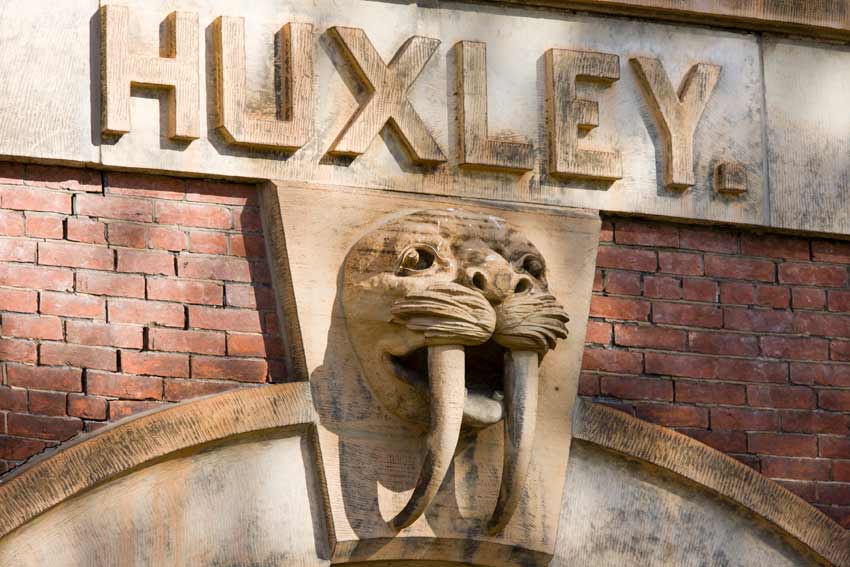

The names and animal heads carved into the building’s façade are what remain of the Lewis Brooks Hall of Natural History, built in 1876 and opened to the public two years later. Funded by its namesake, a northern textiles magnate, and designed by J. R. Thomas of Rochester, New York—whose designs, housed in Special Collections, are clearly marked as intended for UVA—the museum was established during an American renaissance of natural science.

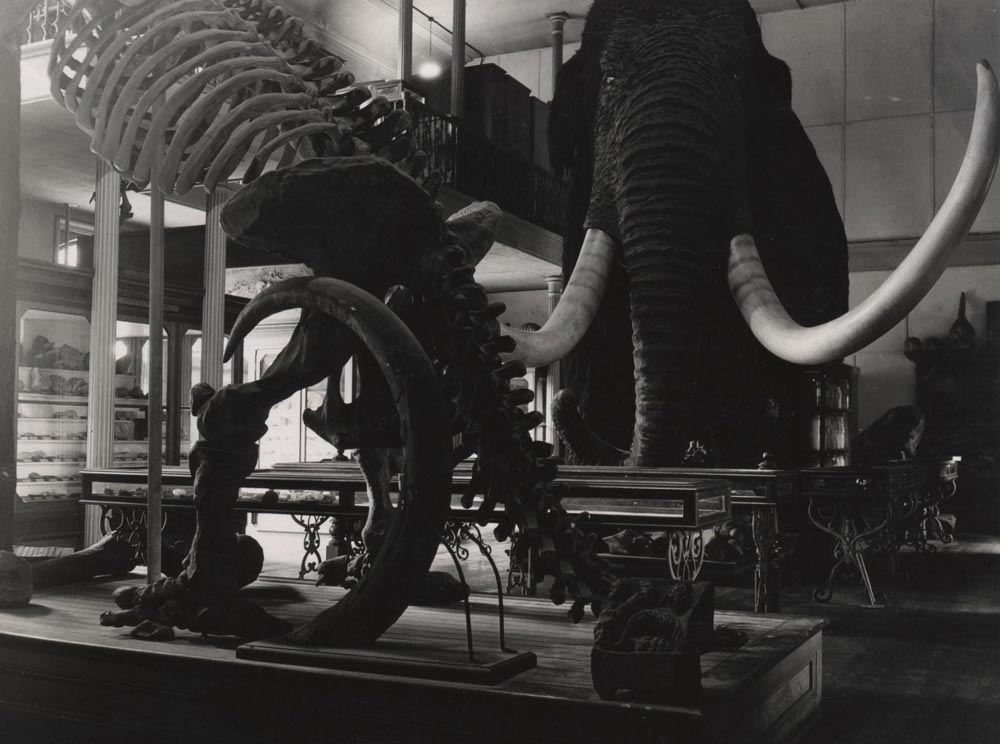

The University hired Henry Ward, a naturalist, scholar and entrepreneur who preserved an elephant for P.T. Barnum and buffalo heads from hunting trips with Buffalo Bill Cody, to gather the museum’s collection. He packed Brooks Hall with glass cabinets full of more than 25,000 fossils, skeletons and botanical and geological specimens. He also brought in a life-size model of a Siberian mammoth and a full cast of a dinosaur skeleton for the museum’s main hall.

According to the research of UVA anthropology professor Jeffrey Hantman, who wrote about Brooks Hall for the Albemarle Historical Society in 1989, the museum was praised by scholars and the press for its size and completeness. It drew enough traffic that the Board of Visitors had to hire a janitor and two natural history professors to help guide visitors through the hall.

By the 1940s, interest in the exhibits had declined, and the museum closed in 1948. Brooks Hall was converted into classrooms and faculty offices. For at least 30 years before, people had complained that the building was an eyesore. But the building’s strange façade continues to a do a musem’s work: it provides what architectural history professor Richard Guy Wilson calls “a history of natural history.” It’s right there in the names and animal grotesques carved in limestone on the outside walls.

The names ringing the building belong to prominent natural historians, from Aristotle to James Hall, a paleontologist, who was still alive when Thomas drew up his plans. They form a timeline of the evolution of the discipline of natural science.

The significance of the 12 animal grotesques that sit below the names remains a mystery. Hantman identified a Mr. Mann as the workman who carved and finished the different animal heads in exquisite detail. Wilson suspects Mann did his work off site, using photographs and scientific illustrations as his guide, then shipped them to Charlottesville by train, most likely from New York.

While the carvings are detailed in the building's architectural plans, their positions change throughout the drafts, and none match with how the animals now appear on the building.

“From walking in and out of the building every day, to consulting with paleontologists, I have never been able to sort it out,” says Hantman in an email.

Wilson has an idea. Sometimes, he says, “things are done by accident.”

Grotesques

Get up close and personal with the 12 grotesques.

Hantman believes that this grotesque could be a take on the 19th century idea of the "ape-man." Dan Addison