Modern Honor

Honor's single sanction barely survived a vote. Now what?

When Landon Wilkins attempted to travel back in time through the Cavalier Daily archives, he found himself stuck in the present. He was researching some modern history of the University of Virginia Honor System, including the single sanction, the system’s one-and-done penalty of permanent expulsion for culpable lying, cheating or stealing. As op-eds from the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s lit up his screen, he felt a shudder of déjà news.

“It was scary when I was reading it,” Wilkins (SCPS ’16, Educ ’17) says. “The same things are happening over and over and over again.”

Return to Grounds after at least a decade’s absence and you’ll experience something similar. The back-and-forth of a sanction debate takes you back, like hearing the low rumble in the Charlottesville night of a passing coal train. The Honor System penalty came up for its first vote of confidence in 1972. For every generation since, lulls in the 1990s notwithstanding, voting on the sanction has become as much a part of the UVA student experience as navigating the Alderman Library stacks, processing down the Lawn and brunching Sundays on Advil.

If it seems like some things never change—Groundhog Day on Grounds—it’s not. What had been an occasional questioning of the single sanction has become a steady drumbeat. Six proposals to add lesser Honor penalties have come to a vote in the last 11 years. That’s a pace of attack not seen since 1986, when the single sanction survived six reform votes in eight years. Back then, support of the status quo grew stronger with each successive vote. This time, the momentum has been building for change.

The Senf Gates were given in 1915 and were meant to show support for the Honor System.

In February, the latest vote, the single sanction hung on by the single thread of a single percentage point, 85 votes shy of the 60 percent supermajority needed to amend it. Had the counterproposal passed, it wouldn’t have changed the sanction overnight, but it would have granted the Honor Committee new power, and a mandate, to develop a system of lesser penalties.

The frequency of the votes, their accumulating tilt toward reform, and a new generation that seems culturally predisposed to a more forgiving social contract, raise the question of just how long the expulsion sanction can stay single. And, if lesser forms of discipline become a part of the Honor System, what does it mean for the health and character of capital-H Honor at the University of Virginia? The answers may surprise you.

It’s not about the sanction

Faculty on the frontlines will tell that you inquiries about the sanction miss the point. Kenneth G. Elzinga, longtime faculty adviser to the Honor Committee and a living legend since shortly after arriving in 1967 to teach economics, says people shouldn’t assume he’s necessarily pro-single sanction. He may well be. You just can’t trap him into saying it, no matter how many crafty ways you pose the question.

“What I’m really in favor of is the student self-governance,” Elzinga says. To him, the Honor System works because the students own it and operate it. If they want to rejigger the procedures and penalties, that’s their business. The key is that they embrace Honor and endeavor to foster a community devoted to it.

“I appreciate it as a professor. It’s an enormous time saver,” he says. If a student claims she missed a test because of a migraine, and asks to take the makeup, “I don’t need to see something from Student Health.”

So how do you answer the traditionalists who ask: What part of “Do not lie, cheat or steal” do you not understand?

And trust begets trustworthiness. Take a student at her word, and she will walk a little taller in all her dealings. “In some reverse-feedback way, it makes people more honest,” Elzinga says. “It’s part of the magic of the Honor System when that happens.”

That magic, in Honor parlance, is the “community of trust.” Darden School of Business Professor Michael Lenox (Engr ’93, ’94), an associate dean and a past Honor Committee chairman, attests it’s a distinctly UVA phenomenon. He has taught at some of the country’s most prestigious universities, including Harvard, Stanford and New York University. He says he has uncovered cheating elsewhere—he won’t say on the record where—and a general indifference toward the subject among both students and faculty.

Not so in his eight years’ teaching at Darden. “There’s something fundamentally different occurring at UVA that you don’t see at other institutions,” Lenox says, and it’s not because of the single sanction. “The hallmark is the student self-governance piece.”

Journalist and media studies lecturer Coy Barefoot (Grad ’97), who has done extensive research on the history of the Honor System, similarly reframes a discussion about the sanction. Instead of focusing on Honor’s polemics or periodic scandals—basketball star Olden Polynice’s 1984 Honor acquittal, for example, or 2002’s sanction of 48 introductory-physics plagiarists—he points to the daily miracle of how the system functions at its most mundane level.

“She takes that test. She signs her name that she won’t cheat, and she doesn’t cheat because she signed her name,” says Barefoot, who helps lead the Center for Media and Citizenship. “It happens many thousands of times every school year, and it never makes the headlines.”

Built-in suspension

Something else to consider: An alternative sanction already exists. At least, you can make that argument.

For those who would defend a status quo, Honor has never really had one. Barefoot’s thesis, chronicled in this magazine’s Spring 2008 issue, is that the UVA Honor System has undergone continual change since its inception. Honor started as a simple pledge, the “I have derived no assistance” formulation that professor Henry St. George Tucker coined in 1842, a variation of which students affix to assignments today. As that oath acquired rules in the decade following the Civil War, Honor grew from a pledge to a code. When a permanent Honor Committee took form to administer the rules in 1913, Honor transformed from a code to a system. And that system has accreted more complexity ever since. Says Barefoot, “The story about Honor at UVA is that it has evolved and it is always evolving.”

On the modern evolutionary timeline, 2013 is when the asteroid hit.

That’s the year 64 percent of students, in a referendum with a relatively high 39 percent turnout, voted in a mechanism called “informed retraction.” If you’ve received notice you’re under suspicion for an Honor offense, informed retraction gives you a seven-day window to confess and request a two-semester suspension.

Informed retraction is the Honor System’s rough equivalent of copping a plea: Facing the prospect of permanent expulsion, the accused has the opportunity, a heavily conditioned one, to bargain for a temporary leave. For the first time in UVA Honor history, the bylaws codified a suspension penalty.

To be sure, informed retraction’s suspension option, with its seven-day fuse, is an exploding offer: first-timers only, one to a customer, and you must act now. Miss it, and events proceed to trial, then you’re back to a single-sanction system. When it comes time to render a verdict, the rules restrict the jury to the Honor System’s traditional binary choice—expulsion or acquittal and nothing in between.

Informed retraction is an expansion of conscientious retraction, which got Honor-codified circa 1981–82, according to the research Wilkins, an Honor Committee member, turned up as he pored over digitized Cavalier Daily back issues. Conscientious retraction affords a student a complete defense to potential Honor charges if he formally confesses before coming under suspicion.

Both forms of retraction add to the procedural complexity that makes up today’s Honor System. Including those tandem opportunities to confess before or after being suspected, some 11 different safety valves exist at crucial junctures in the modern apparatus of Honor to prevent permanent expulsion.

Compare that to an earlier time, when an Honor accusation came in the form of a knock at your door, an Honor trial was the conversation you had after you opened it, and a post-judgment appeal consisted of your requesting a hand with your bags.

Generational half-lives

What makes February’s near-win for alternative sanctions so striking is that it came just three years after the passage of informed retraction, a major reform in its own right. It’s why, in the turnabout of the modern-day sanction debate, the biggest advocates of informed retraction are the single-sanction traditionalists. During the lead-up to this February’s vote, single-sanction defenders used informed retraction as an example of the Honor System’s give, and urged restraint: Let informed retraction’s effects play out before introducing any more major changes.

The dynamics of contemporary culture, however, made forbearance a losing argument. They were preaching “Go slow” to an electorate characterized by impatience. Patricia Lampkin (Educ ’86), the University’s vice president and chief student affairs officer who has observed student life over the last 37 years, used to measure the generations in decades. She could distinguish students who attended in the early 2000s from those here in the 1990s from the 1980s crowd. Then she started discerning cultural demarcations at five-year intervals. Now it seems the culture changes every few years, she says. Attribute it to faster flow of information, social media’s contagious spread of ideas, or technology-induced attention deficit disorder. Whatever the cause, Lampkin says, “The generations are condensing.”

As time has collapsed, so has some degree of patience. Faith Lyons (Com ’16), who just completed her term as Honor Committee chair and supports the single sanction, sees a certain cultural angst as part of the reason the lesser-sanctions vote came so soon after the adoption of informed retraction. “My generation in particular, there’s been a lot of distrust of institutions, the Honor System included,” she says, although she sees more education and communication as a solution.

Honor speak

It may also be a generation uncomfortable passing judgment on peers in the way the Honor System requires. Economist Elzinga has observed that while students will follow the highest standards of honor for their own conduct, they’re reluctant to hold someone else to similar account. As he describes the attitude, “Who am I to inflict my morals on somebody else—impose my values upon them?”

Lampkin makes a similar observation. “One of their strongest attributes as a generation is their acceptance of diversity and multiculturalism and people different from themselves,” she says. Because of those same qualities, “they are less willing to judge their fellow students’ behavior,” including, she says, if they’ve witnessed an Honor offense.

Lyons rejects such a generalization. She points out it was an earlier generation, not hers, that repealed the longstanding provision that made it as much an offense to ignore an Honor violation as to commit one. The so-called non-toleration clause disappeared from the Honor rules around 1989, and a vote to revive it failed in 2005, according to Cavalier Daily accounts. So, Lyons will tell you, don’t brand her generation as being more conflict-averse than any other.

Even so, the current student body has shown itself to want a kinder form of Honor. Eric MacBlane (Engr ’16) co-led the multiple-sanctions campaign this last election cycle. With the logic of a systems engineer, a financial mathematician, a future management consultant and a past high school debater—he’s all those things—MacBlane marshals his talking points. He and his team analyzed all the arguments for sanction reform and zeroed in on three.

The first two were clinical. They argued that the severity of the single sanction freezes students from leveling accusations and student juries from issuing convictions. MacBlane admits that’s a long-running debate, each side having ready counters to the other’s arguments.

In fact, in a 2012 student poll, 51 percent of 977 respondents wavered when asked if they would report an Honor offense if they witnessed one. Then again, only 4 percent answered with an outright no. In a question drawing broader participation, 35 percent of 4,126 respondents indicated the single sanction might deter them from reporting an offense, although only 9 percent said so categorically.

To Lyons, the recent Honor chair, hesitation isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “Reporting someone for an Honor offense isn’t easy, whether you’re 100 percent sure or 20 percent sure,” she says. “People struggling with that decision doesn’t make me worry about the system.”

It was MacBlane’s third argument, he says, that best connected with students—that a single-sanction Honor System is too rigid. Students make mistakes. We’re a learning institution. Under the right circumstances there should be the opportunity to let a student atone and find his way back into the community.

Mercy over justice, the spirit over the letter—it has an almost irresistible appeal. But how would MacBlane answer the traditionalists? Historically, the essence of the UVA Honor Code has been the moral clarity with which it sets the most modest of expectations for academic conduct: Tell the truth, do the work, respect others. Replace the bright line between right and wrong, and the direct connection between action and consequence, with gradients of gray, and you’ve unmoored a values system and set it adrift in relativism.

Put simply, what part of “do not lie, cheat or steal” do you not understand?

MacBlane’s answer: “For me it’s just about forgiveness. That might be a cultural shift,” he says. “Our culture is now more about forgiveness.”

Call it a generation that believes in Honor but also in the grace of second chances and softer edges. You see it in Honor’s new vocabulary. A series of bylaw changes took effect in August, intended to give the system a less adversarial look and the proceedings a less criminal, more administrative feel. Honor counsel became “advocates.” Trials became “hearings.” Juries became “student panels.” Verdicts became “decisions.”

The Honor Committee also flirted with changing guilty and not guilty to “responsible” and “not responsible,” the Cavalier Daily reported, but enough Honor officers had had enough. The linguistic corrective failed to pass.

Where we go from here

So, with sanction alternatives coming up for a vote just about every other year, with a wave of reform reaching one percentage point’s proximity to the tipping point, and with an electorate that seems to yearn for a form of Honor that puts less burden on both accuser and accused, how soon before Honor panels use a sliding scale of penalties instead of a single bullet to address academic fraud?

The short answer is probably not for a few years, maybe longer. In response to February’s 59 percent vote with a better than 34 percent turnout, Lyons’s Honor Committee called for creation of a review commission to audit the status quo, survey the students and study best practices. It will include students, faculty, administrators, alumni and members of the Board of Visitors.

Matt West (Col ’17), who succeeded Lyons as Honor chair in April, says the commission’s report should come in the spring of 2018. He would expect reformers to wait for the results before trying to put new alternatives on the ballot. That doesn’t preclude them, he says, but “I would say it will be somewhat less likely.”

If Lampkin is right, that the zeitgeist zigs and zags every few years, it’s possible popular opinion could swing back in favor of the single sanction. That’s especially true as informed retraction undergoes refinement and takes hold.

But all of that, as Elzinga pointed out at the start, misses the point. The most important thing isn’t how the sanction debate comes out. It’s that students care enough to have the debate. As Wilkins discovered while traversing the Cavalier Daily archives, the passion about the Honor System is as intense today as it was more than 30 years ago. That may well be the better indicator of the health and character of Honor at UVA than what happens to the single sanction.

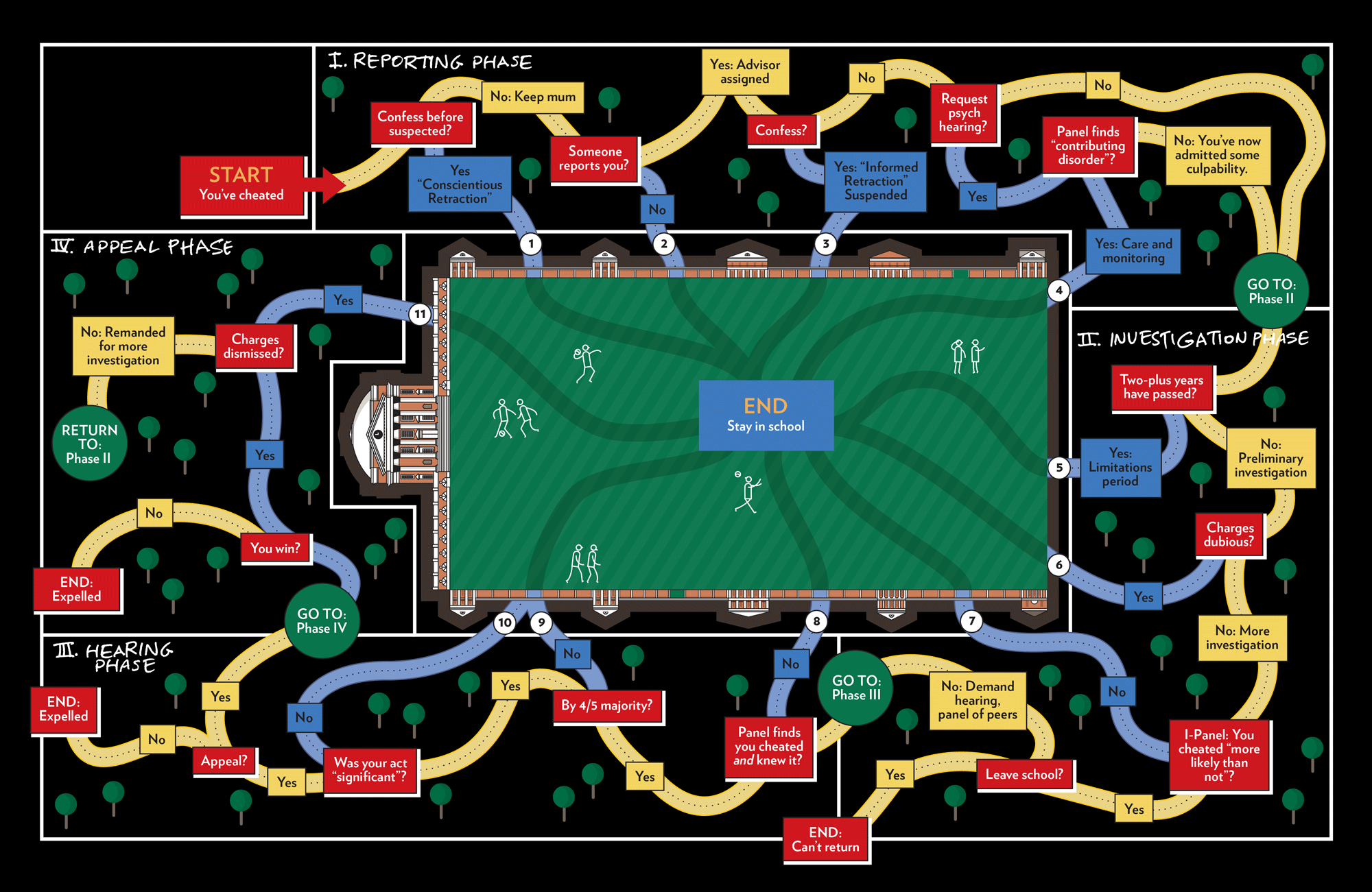

Modern honor’s due process path

The System provides at least 11 routes to avoid expulsion:

Infographic by Newhouse Design