Can Social Networking Spur a Revolution?

UVA expert says not to confuse people with their tools

Naming children after revolutionary heroes is nothing new, but one Egyptian father gave his daughter an unusual name at the height of the recent uprisings in the Middle East.

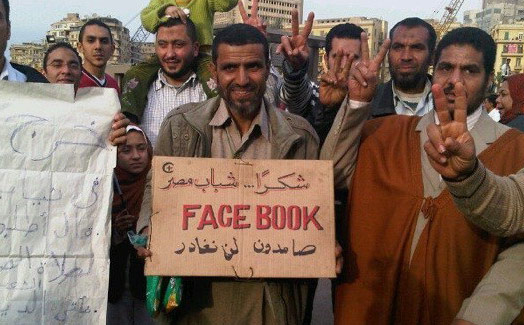

Jamal Ibrahim named his firstborn child “Facebook,” a tribute to the role of social networking during social unrest.

While Facebook, Twitter and other sites proved invaluable in keeping Egyptians connected during the revolt, one UVA expert says it’s important not to confuse the tools with the people who use them.

“We’re in danger of forgetting that [people] put themselves on the line to make this happen. People were killed, people were tortured, people were gunned down in the streets,” says Siva Vaidhyanathan, a media scholar, cultural historian and professor of media studies at UVA.

“This is one of the great mysteries of activism,” he says. “No one’s really sure where the tipping point comes, when you feel confident enough that there are enough people to stand with you and face down the gun.”

Egyptian activists Wael Ghonim and Ahmed Salah, both of whom were imprisoned by the Egyptian government for their roles in the uprising, credit social networking websites as platforms for planning protests and sharing news from Tahrir Square in real time. Ghonim told CNN, “This revolution started [...] in June 2010 when hundreds of thousands of Egyptians started collaborating content. We would post a video on Facebook that would be shared by 60,000 people on their walls within a few hours. I’ve always said that if you want to liberate a society, just give them the Internet.”

Media experts have disagreed to what extent social media played a part in the uprisings. Some, like Atlantic Magazine blogger Andrew Sullivan, hold that networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter were instrumental in spurring people to the streets. Writing about Tunisia, he said: “In that revolution, the ability to upload videos of police brutality and post them on Facebook was central to why, this time, the movement spread.” Then there are others, such as Malcolm Gladwell, who debunked this idea in a New Yorker article, in which he says social media create only thin networks that don’t have the ability to compel people to engage in high-risk activism.

Who’s right? “No one really knows,” says Vaidhyanathan. “The reason no one really knows is because there’s no simple answer.”

Vaidhyanathan, a frequent contributor to NPR and the New York Times Magazine, approaches the question in a historical context. “Social upheaval and political revolution can happen with or without social media,” he says. “The other thing we know for sure is that many millions of people in both Egypt and Tunisia use social media. Many of them actually did use Twitter or Facebook to communicate with someone during the uprising.”

However, he points out that for four days during the Egypt revolt, the Internet and phone service were cut by the government. “During the hottest four days, social media was not a factor.

“We desperately need deep analysis of the role of social media in these two events,” he says.

Vaidhyanathan, whose book The Googlization of Everything came out this month, is reluctant to make pronouncements about how social media might play out in the future. However, he does maintain that if the past is any indication of the future, people will continue to adopt technologies for unexpected purposes, in the same way that Facebook was not designed to assist uprisings. “I think it’s safe to say that no matter what the activity, people will use the tools available to them, and they won’t necessarily use them in the way they were originally intended.

“One thing we do know about the digital world,” he says, “is that it constantly surprises us.”

In Disaster, Social Media Keep Victims Posted

When one Japanese woman was separated from her family in Sendai after last week’s tsunami struck, she turned to Facebook.

She learned that her husband and 3-year-old daughter were going to a friend’s house, and they were soon reunited.

“We wouldn’t have found each other for a whole lot longer if it wasn’t for Facebook,” Aika Ortiz told CBN.com.

Such is the power of social media during times of crisis, whether spurred by man or nature. Facebook went beyond simply providing a posting site for friends and families. The website plotted how status updates about the earthquake and tsunami spread across the world in the hours following the disaster, creating the first map of its kind, according to a story in England’s Daily Mail.

In addition, Google provided a “people-finder service” to connect quake victims, and it quickly tallied more than 130,000 postings. Japanese Twitter postings also surged immediately after the earthquake; tweets originating from Tokyo topped 1,200 per minute, according to one tracking service.

In using mobile devices and the Internet during the current tragedy, the Japanese are taking advantage of investments in technology that have put the country well ahead of the global curve, says Siva Vaidhyanathan, professor of media studies at UVA.

“We might only be surprised by the scale because we in the United States don’t have mobile networks and broadband as good as they have in Japan,” he says.

All communications networks are fragile, he added, and mobile devices are at the mercy of batteries and the power to recharge them. That said, cell phones and other devices now have the ability to convey devastation through gripping images, as evidenced in 2004 by the tsunami that struck multiple regions in Indonesia and Asia.

“The only way to make sense of the devastation in so many places … was to follow the thousands of people who picked up their phones and made videos that were posted to YouTube,” Vaidhyanathan says.

The images coming out of Japan are riveting—and potentially motivating for relief efforts, Vaidhyanathan says.

“The real challenge here is can those of us not affected by the tsunami take that next step and realize that voyeurism is not activism.”