At Home in History

Pavilion residents bring personal touches to revered buildings

In the early part of the 20th century, Thomas Jefferson’s notion of the Lawn as a place where professors and students lived and studied together was a grand idea in decline. The University had higher priorities: It was short on space. So it began to co-opt the pavilions for institutional purposes. In 1904, English professor Charles W. Kent was evicted from Pavilion IV to make room for UVA’s first president, Edwin A. Alderman, who needed an office. Other professors also had to pack up their trunks. Pavilion III was refashioned as the Graduate House from 1924 until 1953, and Pavilion VI was vacated for the Romance languages department. Jefferson designed the 10 pavilions with classrooms downstairs and faculty living quarters upstairs, an arrangement that matched his vision of an educational experience in which shared learning infused daily life. Each unit, identified with one of the 10 “sciences useful in our time,” was to be inhabited by the professor who taught that subject. Practically speaking, the pavilions did not give faculty much breathing room. Jefferson, however, did not want to throw off the proportions of his Academical Village, and aesthetic effect reigned. Today, nearly all of the pavilions have been enlarged.

Tenancies used to be extremely long—20, 30, even 40 years. The record holder was Francis H. Smith, chair of natural philosophy, who lived in Pavilion V for 69 years, from 1859 to 1928. Intermingling with students was not always desirable. “Teaching must have stopped pretty quickly in Pavilions II and III,” says Brian Hogg, a senior preservation planner with the UVA Office of the Architect. “We have clear evidence that professors actually built walls behind the windows to block the view into the pavilion from the Lawn.”

Ongoing restoration work, conducted between occupancies, reveals that professors were doing much more than moving furniture around. Pavilion III shows signs of “a complex history of addition and subtraction on the interior, walls appearing and disappearing, a stair being removed, and doors and windows changing places,” according to a 2006 historic structure report.

“Each of the houses has its very particular history,” says Hogg. “Each one got an addition or was changed separate from all the others, so while the exteriors are very much what Jefferson knew, the way the houses have changed over time is very divergent.”

As appreciation for the Academical Village and Jefferson as an architect has grown, the Lawn’s original purpose has ascended again. Those offered pavilion residency must want to participate fully as a member of what the founder envisioned: “a community of faculty and students living together and working together,” as the Board of Visitors’ official policy states. Some residents say that the privilege of living on the Lawn is unequaled.

As Pavilion IV resident Larry Sabato (Col ‘74) sees it, professors are temporary tenants of a priceless legacy. “We have the obligation to preserve and share these spaces during our limited time here,” he says.

Here we invite readers inside those spaces.

Pavilion I

Robert Pianta, dean of the Curry School of Education

For Robert Pianta, the greatest pleasure in occupying a pavilion lies in turning the knob and opening wide its front door.

“Each morning, I retrieve the newspaper and just stop for a moment and look out at the Lawn and the Rotunda,” he says. “That time of day is quiet, and it’s possible to get a sense of the space as it’s been present throughout history, and to appreciate how beautiful it is and how special it is to live there.”

Pianta, who has spent his entire academic career at UVA, says he and his family always wanted to live on the Lawn; they lodged in Pavilion III until Pavilion I was ready for them in 2009. Their decision not to wait was spurred by their daughter Meghan’s impending graduation from UVA in 2008; what else could match as a venue for celebration?

Pavilion II

Meredith Woo, dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences

Meredith Woo and her family moved into Pavilion II in the fall of 2009, following a $2.2 million renovation. Having spent much of her adult life restoring old houses to their former glory, Woo was struck by a key difference as she set about making Pavilion II her home.

“It cannot be retrofitted for modernity, however thorough the renovation may have been,” she writes on her UVA blog. “Rather, modernity gets retrofitted to accommodate the old house.” So while Pavilion II now boasts central heating and air conditioning, new plumbing, wiring and fire detection systems, it still lacks closets, and the small kitchen precludes installing a gas stove.

Like others who live on the Lawn, Woo has become a student of her pavilion, completed in 1822 in the Roman Revival style. “Jefferson fretted over the last details of the design, down to the quality and cost of the bricks with which to build this home,” Woo writes. Abutting the Rotunda on the east side, the pavilion survived the Rotunda fire of 1895 by dint of a bucket brigade, which covered its north side with wet blankets.

“It is a house with significant history, and history is always a burden, even as one learns from it,” she continues. “In moving into the pavilion, I did not have the freedom of the typical homeowner to do as I pleased—the kind of willful and rebellious ignorance one sometimes yearns for, and is politely denied, at the University of Virginia.”

When she steps out the back door, though, she is glad that individual taste doesn’t always prevail. The terraced garden, enclosed by serpentine walls and presided over by an ancient bigleaf magnolia, is a favorite spot. A quiet refuge, it’s been cultivated with care. For Woo, it recalls “what John Donne might have called ‘a little world made cunningly,’” and, like the entire Academical Village, she says, it is a place meant to be shared.

Pavilion III

Harry Harding, dean of the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy

Harry Harding gets a forceful reminder of Jefferson every time he walks into his basement kitchen: He has to duck. The extremely low doorways on the ground floor are but one of the quirks that he has adjusted to since becoming a tenant in April 2010.

“Jefferson was an absolutely brilliant amateur architect,” says Harding, “and so as one appreciates his brilliance, one also occasionally curses or suffers under the amateurish features here and there.” Considering the fact that Jefferson himself was quite tall—over 6 feet, like Harding—his decision to shrink proportions is curious.

The pavilion’s original windows have “the soundproof quality of a sheet of paper,” he adds, but the doors are absolutely solid, capable of blocking out most of the Lawn’s ruckus. Add it all up and Harding, an architecture buff, is unequivocal: “This is the most magical experience of my life in terms of a place to live.”

Pavilion III was the most expensive pavilion to build. The Corinthian capitals of its two-story portico, which are Carrara marble, were considered highly extravagant by everyone except Jefferson.

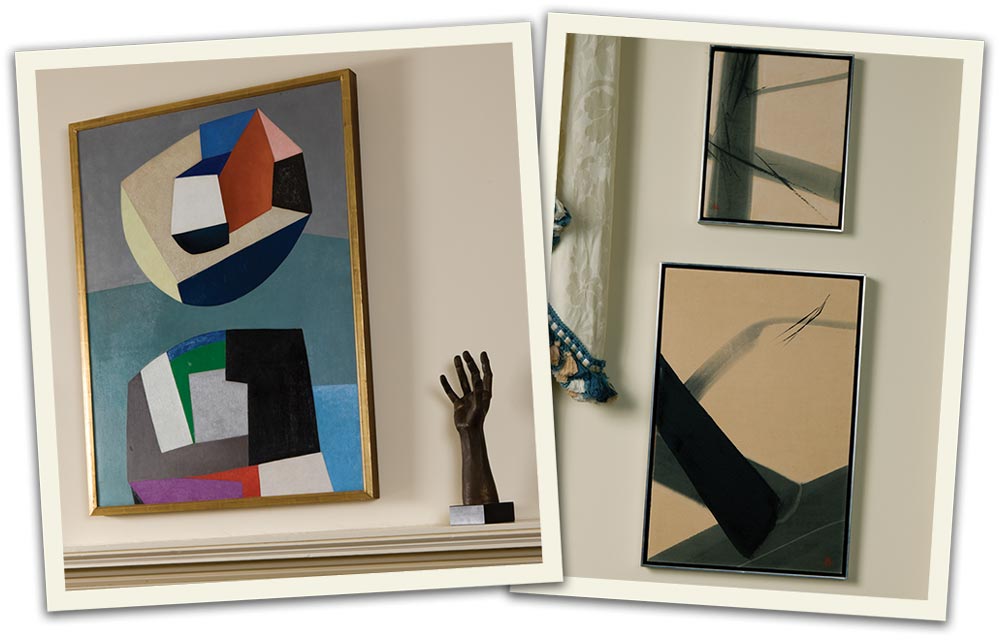

Inside, Harding has supplied his own exotic touch. Most prominent is his collection of Asian art, many of the works by Toko Shinoda, a Japanese contemporary female artist. Harding inherited the sizable collection from his father, who began acquiring her paintings in the 1960s. Antique travel posters are also on display.

It’s an eclectic backdrop for an equally unusual event that Harding has enjoyed hosting since becoming a pavilion resident: flash seminars. These ad hoc intellectual discussions bring students and professors together outside class for the sheer love of learning—no grades, no credits. “They are very easy to arrange,” he says. “We get a bunch of chairs and what students like in terms of snacks and drinks, and we just go at it.”

Pavilion IV

Larry Sabato, director of UVA’s Center for Politics

Larry Sabato counts himself unbelievably lucky to have had “two turns at bat,” he says. He lived in Room 16 East as a fourth-year and, since 2003, has called Pavilion IV home as a professor of politics.

“I love the community spirit. There is always something going on,” Sabato says. “Every student resident has at least a half dozen passions, and you learn about them as you get to know your neighbors.”

With so many gatherings held in the pavilions and gardens, he gets to meet people from throughout the University and beyond, visiting for conferences or to conduct research. “All universities are compartmentalized today,” says Sabato, “but the Lawn is an interdisciplinary antidote to overspecialization.”

Pavilion V

Patricia Lampkin, vice president and chief student affairs officer

One Lawn family has bounced around a bit more than others. They lived in Pavilion VIII from 1988 to 1992; in Pavilion III from 2005 to 2008; and in Pavilion V since 2008. Their children, born while the family lived in Pavilion VIII, probably consider it normal to have grown up in a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Pavilion V, with its impressive six-columned portico, is by far their favorite—“although I would say, when we were in Pavilion VIII, that it more than suited our needs,” says Pat Lampkin (Educ ‘86). But for entertaining, their current home wins hands down. “It’s the most commodious and the kitchen is on the main floor,” adds Lampkin’s husband, Wayne Cozart, vice president of development for the UVA Alumni Association. Pavilion III, which was originally the largest of the pavilions, is now the smallest; it doesn’t have an addition, and a flight of narrow steps connects its basement kitchen with the dining room on the first floor.

Each pavilion is quite different on the inside, but they all possess the same inimitable quality. Tenants often remark on it. “The size and height of the rooms and Jeffersonian features make it a very calm and pleasant environment,” says Cozart. “When I come home, my anxiety level drops by half.”

With their unprecedented record of pavilion hopping, the couple is often quizzed by other faculty who are considering the invitation to live on the Lawn. Says Cozart: “We ask them what they want or enjoy when they come home,” and how they answer that question usually indicates whether they will like or loathe the arrangement.

The couple has always considered their first floor to be public space, available for classes and special functions, some of which have slipped into annual tradition. “The event that we try to do every year is a midnight breakfast for Lawn residents during exam week,” says Lampkin. The menu varies, but not the hungry hordes. “The group usually broadens beyond Lawn residents, but we try to provide a home-cooked breakfast,” she says.

Pavilion VI

Bob Sweeney, senior vice president for development and public affairs

When Bob Sweeney opens his pavilion to visitors, he likes to open all of it—all three floors. “So people get the flavor of it,” he says. There isn’t a careful division between public and private. If he sees a tourist or total stranger looking in, he often surprises them by asking, “Would you like to see what it looks like?”

By his own reckoning, he has hosted more than 60 events in his pavilion this year. “You might think that because of my job it would primarily be donors, but I have almost as many students and faculty groups, programs and classes in my house.”

Equally impressive? “I don’t have a housekeeper,” he says. “I clean up.”

Pavilion VII: The Colonnade Club

The first structure to be built in the Academical Village, its cornerstone was laid on Oct. 6, 1817, in the presence of James Monroe, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. The pavilion housed the University’s library in its upstairs rooms until the Rotunda was completed in 1826. It also served as an unofficial faculty center and, in 1832, as a place of worship when the University hired a chaplain.

It is the only pavilion that is not a faculty residence. Since 1907, it has been the address of the Colonnade Club, organized to enhance social and intellectual interaction among faculty and alumni. The club also functions as a hotel.

Pavilion VIII

John Colley, professor of business administration, Darden School of Business

“The first thing I wanted to make sure of was that it had an indoor bathroom,” says John Colley. Surveying the Lawn from the balcony of his new digs, he is grinning from ear to ear.

It’s a quiet morning in May, a few days before graduation, though UVA police told him the Lawn was aswarm with 30 streakers last night and 40 the night before. No matter: With brick walls a foot thick, Colley’s second-floor apartment is remarkably insulated. Unlike the other pavilion residences, Pavilion VIII is not a single-family home; the first floor contains the University Guides office and classrooms. Another apartment on the terrace level is occupied by Pamela Pecchio, an assistant professor of art.

Colley gives a visitor a tour of his rooms, high-ceilinged and still half-furnished, often interrupting himself to exclaim over the craftsmanship evident everywhere, from the cornices to the white marble Corinthian columns. In April, he became the first Darden professor who is not a dean to live on the Lawn.

A recipient of the 2010 Thomas Jefferson Award, Colley sees his presence as an important link between Darden and the Grounds, a connection he has tried to foster during his 44-year teaching career at UVA. His “Reading Seminar on Jefferson,” taught with help from UVA and Darden alumni, is full every year and has been completed by about a thousand Darden students—small groups meeting in eight sections a year over the past decade. The huge dining room table in his apartment—inherited from the previous tenant—should be perfect for another Lawn seminar he wants to introduce for smaller groups of students.

In a small room facing the Lawn that he has made into his home office, Colley points out another treat; in winter, when the trees are bare, the Rotunda will all but fill his view. “I’ve got to say this is the honor of my life to have the privilege to live here,” he says.

Pavilion IX

Dorrie Fontaine, dean of the School of Nursing

Nominees for pavilion residency often decline the offer because of the anticipated lack of peace and privacy, frequent social demands and the unavoidably semi-public lifestyle. It is fair to say that Dorrie Fontaine, who moved into Pavilion IX in July, hopes that this rental deal comes as advertised.

“I’m going in with the attitude, ‘what a privilege it is to live here and be part of the students’ life,’” she says.

Fontaine took the house keys from Karen Van Lengen, former dean of the architecture school, who shared her knowledge of its history, unusual spaces and architectural flourishes, from the exedra—the curved, recessed entrance that Jefferson modeled after the Hotel Guimard in Paris—to the triple-sash windows residents can throw open to stroll across the rooftop walkway.

More mundane matters, like traffic (students will steal your parking spot) and noise (one side of the house faces the amphitheater) are combated with ear plugs and the right attitude. Fontaine accepts all of it with the unfazed enthusiasm of an adventurer. “Everything is doable,” she says.

“Just as students can be noisy, I might have some noisy parties while they’re trying to study,” she adds. “We should talk about this as a two-way street, right?”

In recent months, as she has checked on the progress of renovations before her move, Fontaine has surveyed all the blank plaster walls and seen the potential for making her own mark. “There are these long hallways on each level, and I want some rotating exhibits of some of our nursing history pictures,” she says. “We have one of only two nursing history centers in the States, and we have beautiful old portraits from the early years.”

Fontaine has a great many other plans, too, that will have much of the University community knocking at Pavilion IX’s door. “I’m going to be keeping it very busy,” she promises.

Pavilion X

Carl Zeithaml, dean of the McIntire School of Commerce

When his 10-year lease runs out this summer, Carl Zeithaml says he will miss his strong friendships with his younger neighbors. Each group of 54 “Lawnies” has its own personality and culture, he says, and though these students move out every year, they circle back quite often.

“Lawn students have stayed with us when they were sick or injured, and they frequently come back to visit us after they graduate,” he says. “We have attended their graduation parties, their weddings, and we stay in touch with them years later.” Two Lawnies remain in very close touch: Two of Zeithaml’s children are married to them.