The Song Collector

How folksinger Paul Clayton brought the music of Virginia to the world

Folk music traveled in the back seat of Paul Clayton’s beat-up car in the form of a tape recorder he used to capture the beautiful and obscure mountain ballads of central Virginia. He brought them to Greenwich Village folkies, who were always on the lookout for new songs for their repertoire. Over a decade and a half, Clayton made countless trips between Charlottesville and New York, sharing his enthusiasm and melodies with musicians on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line.

Followers of American folk music will probably be familiar with the Gaslight Café in Greenwich Village, the 1960s-era musical mecca where young folkies like Bob Dylan launched their careers by passing the basket during late-night open mics. But UVA alumni may be more familiar with the other Gaslight Restaurant, the nexus of Charlottesville’s own folk milieu. Wandering down West Main on an evening in the early ’60s, they may have heard the twinkling of dulcimer strings coming from an open door. If they stepped inside on a special night, they might have seen Paul Clayton (Col ’53, Grad ’57) take the stage with Dylan, Mike Seeger and Bill Clifton to play some of the oldest and rarest folksongs to be found in Virginia.

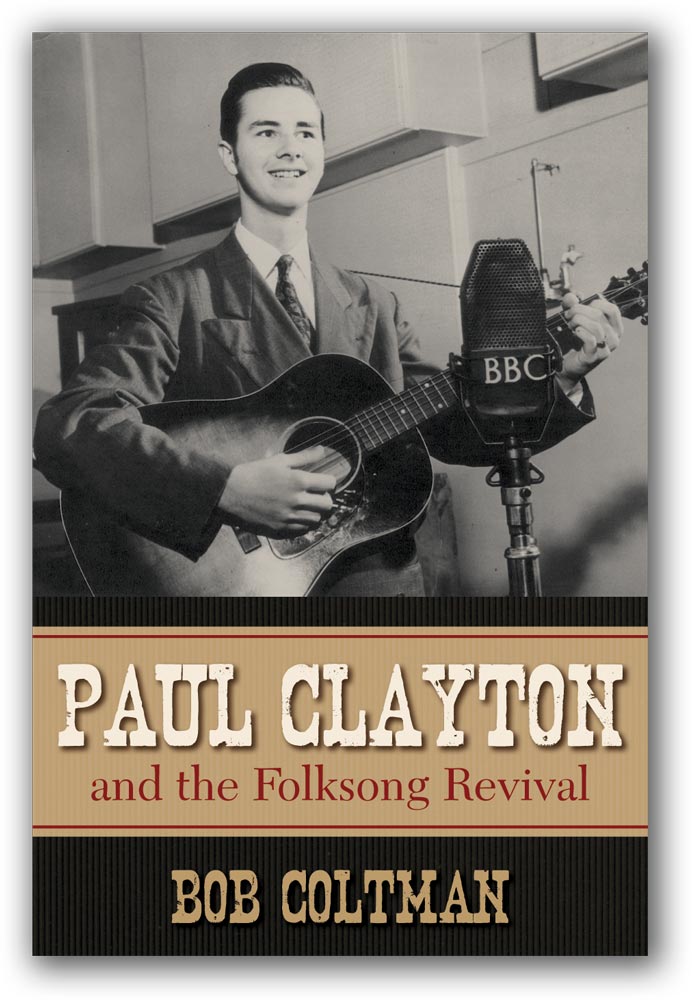

Born in 1931 in New Bedford, Mass., to a family who sang old whaling songs, Clayton is legendary among hardcore folkies and historians of Charlottesville’s rich music scene. But he never gained wide recognition during his lifetime or since his death in 1967. As biographer Bob Coltman suggests, despite his recording almost 20 full-length albums and his considerable influence on Dylan and others, Clayton remains a folksinger’s folksinger, admired and respected more for his deep knowledge of Virginia folksongs and tireless song-collecting efforts than for his own material.

Clayton arrived at the University of Virginia in 1949 and studied with Arthur Kyle Davis Jr., a scholar of folksongs and author of 1929’s Traditional Ballads of Virginia. Later, as a graduate student, Clayton helped produce More Traditional Ballads of Virginia, writing deeply researched headnotes and transcribing tapes buried in the archives of the Virginia Folklore Society.

Outside the classroom, Clayton rambled across the countryside hunting songs. His travels took him across the U.S. and to parts of Europe and Africa, but his home base was always a remote, primitive log cabin in the area of western Albemarle County known as Brown’s Cove. The cabin became both an artistic retreat for Clayton and the site of some wild parties, according to Coltman, but it also served as the launching point for his song collecting. He was responsible for “discovering” a number of singers and pickers in the area, including Mary Bird McAllister, whom Clayton recorded singing songs like “Across the Blue Mountain to the Allegheny” in the late ’50s.

Dylan visited Clayton’s cabin and spent his 21st birthday at a party thrown by Clayton in the Charlottesville apartment of Steve Wilson, one of Clayton’s closest friends. Dylan had met Clayton in 1961 when both were making nightly rounds of the Greenwich Village folk clubs. But Dylan was familiar with Clayton before they met; a version of the song that comes closest to Clayton’s “big hit”—“Gotta Travel On”—can be found on the earliest recording Dylan made, 1960’s “St. Paul Tape.”

In 1964, Dylan told an interviewer that a folk song “goes deeper than just myself singing it, … it goes into all kinds of weird things, things that I don’t know about, can’t pretend to know about. The only guy I know that can really do it is a guy I know named Paul Clayton, he’s the only guy I’ve ever heard or seen who can sing songs like this, because he’s a medium, he’s not trying to personalize it, he’s bringing it to you … Paul, he’s a trance.”

Dylan, notorious for reaching into other people’s song bags for material of his own, created a controversy when he recorded “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” whose lyrics were partially but quite obviously lifted from Clayton’s song “Who’ll Buy You Ribbons (When I’m Gone).” Lawyers for the two men became embroiled in a legal rift over rights to the song, but Clayton’s affection for Dylan ensured that the two remained friends throughout.

Though he held the copyright to the song, Clayton couldn’t ultimately claim clear ownership of the work, because its origins appear to have been in the public domain. “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens” was a song Clayton claimed he learned from Mary Bird McAllister. He modified the lyrics and kept the melody. Then along came Dylan and did the same thing—classic folk composition in action. Clayton settled for a small sum, but the incident emphasizes the folk song as an embattled form straddling collective composition and individual authorship. Clayton’s catchphrase has been quoted by more than one participant in the Greenwich Village scene: “If you can’t perform, write; if you can’t write, rewrite; if you can’t rewrite, copyright; if you can’t copyright, sue.”