Nevermore

The stolen treasures of Alderman Library

The rarest book in all of American literature walked out of the McGregor Room vault in 1973. So did more than 50 other treasures from the University of Virginia library’s world-renowned collection.

It’s the biggest crime in the history of Alderman Library. Yet, little has ever been reported on it, and little has come to light in the nearly 50-year wait for a solution to the mystery. None of the works has ever resurfaced.

With the help of public records requests and other reporting, Virginia Magazine is able to offer an exclusive look inside the intriguing, and sometimes vexing, sequence of events.

The greatest losses, including that rarest-of-the-rare book, relate to Edgar Allan Poe (Col 1826), inventor of the modern detective story. Fittingly, then, this one begins with him.

The Empty Drawer

The Stella daguerreotype is one of only eight known photographic plates of Edgar Allan Poe. It captures the raven’s black, tousled hair; the long, expressive nose; and those unsettling, asymmetrical eyes. Poe would die of uncertain causes some four months later at age 40, but not before giving the photograph to the woman from whom it takes its name.

In early August 1973, manuscripts cataloger Anne Stauffenberg (Grad ’73) took a small group of co-workers on a tour inside the McGregor Room vault. When she pulled open the drawer to show off the Stella, acquired more than 50 years before, it wasn’t there. Neither was a wooden block or a slip of paper, the placeholders that workers were supposed to use when lending out items.

Also missing: any sense of alarm.

When Stauffenberg reported the disappearance to Edmund Berkeley Jr. (Grad ’61), curator of the manuscripts department, he figured the piece would turn up soon enough. “I was not perturbed,” he would later write in a memorandum to his superiors. “[M]aterials do get misfiled here, and frequently items are gone for months, if they are misfiled.”

So business continued largely as usual at Alderman. “The month of September was a particularly hectic one, with meetings to attend, and a number of complications,” Berkeley would write, “and I did nothing particular about intensifying the search for the daguerreotype.”

In early October, he decided to go through the vault trays himself. In his search for the Stella, he noticed another valuable item missing: an elaborate silver medal minted for Thomas Jefferson’s first presidential inauguration. Berkeley summoned his staff to prepare an audit of the collection. It meant combing through the paperwork associated with UVA’s acquisitions over the decades and creating a 3-by-5 index card for each item so it could be cross-checked against its location.

The Lengthening List

While the cross-checking continued into November, Staige Blackford (Col ’52), who would later become the legendary editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, inquired about getting return of the George Washington letter he had lent the library. He was leaving the governor’s staff to become an aide to University President Edgar F. Shannon Jr. and might need to sell the letter to pay for a house. The staff member sent looking for it reported back to Berkeley that it wasn’t there and, in fact, the box of Washington materials looked emptier than he had remembered it.

With the news only getting worse, Berkeley made an appointment with the associate librarian for the next day. In preparation, he went home and wrote a five-page memorandum, now part of the University Police Department’s investigative file, detailing the months since the Stella was discovered missing. He reported the disappearance of Blackford’s George Washington letter in a section labeled “Events in the Offing Which May Cause Problems.” Under the same heading, he noted that the losing bidder for a recently auctioned Poe daguerreotype wanted to come see the Stella and, well, he needed to come up with a reply in the next few days.

He ended his report with a list of missing items to date. It had eight entries, including the Poe daguerreotype and the Jefferson medal, as well as Jefferson’s personal copy of the 1796 Book of Common Prayer, another treasure.

More stunning were the omissions, based on the final inventory that eventually emerged and that UVA Special Collections keeps on file today. More than three months after Stauffenberg pulled open the empty drawer, the library apparently knew about only a fraction of its losses, and not yet the most dear. They hadn’t realized that Robert E. Lee’s signed General Order No. 9—the stand-down he issued his men the day after the surrender at Appomattox (“I earnestly pray that a merciful God will extend to you his blessing and protection”)—had vanished. Ditto a Mark Twain manuscript, with penciled notes, for Chapter 28 of The Gilded Age.

And then there was Tamerlane and Other Poems, Poe’s first published work and the greatest loss of all. It comprises 40 pages of his boyhood verse. In 1827, the year after he left UVA and struck out on his own in Boston, the 18-year-old Poe had a local printer turn out a limited run for him, by one account only 40 copies. UVA’s copy was one of 12 known to remain, and one of only eight with their paper covers intact.

When a copy (not UVA’s) came up for auction in 1988, The New York Times called it “the black tulip and the Holy Grail of American book collecting.” Christie’s sold one (also not UVA’s) in 2009 for $662,500. Christie’s researcher Rhiannon Knol says UVA’s copy would beat that American literature record today if it’s in better condition.

But then, UVA hasn’t known the book’s condition for some time. As Berkeley’s manuscripts staff continued auditing the collection, their colleagues in rare books, the sister department that shared the vault, did the same with their holdings. As the departments’ checking and cross-checking extended into December, a library patron made a request for Tamerlane. No one could find it. This newest revelation was the equivalent of giving a shoulder tap to someone months into auditing the Smithsonian gem room to point out that, hey, the Hope Diamond is missing.

The final list identifies more than 50 missing items, 35 of them individually described and the remainder made up of an unspecified number of “clipped autographs,” presumably sliced out of historical documents. While she’s not able to appraise those, Knol estimates the 35 enumerated items to be worth more than $1.2 million at auction, with appropriate sight-unseen caveats.

The Poe items predominate, with Tamerlane representing more than half the total; the Stella exceeding $150,000; and another stolen early Poe work, an 1829 edition of Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems, also getting into six figures. Knol puts the Lee order at $80,000 and Jefferson’s prayer book between $30,000 and $50,000. In 2010, Sotheby’s auctioned an autographed Chapter 8 of The Gilded Age for $68,500.

The “clipped autographs,” described as “not as readily identifiable,” entail three batches: the signatures of seven early U.S. presidents, those of Cabinet members in eight 19th century administrations and those of “a number of U.S. congressmen.”

Even after that plodding discovery, more weeks transpired as word of the thefts inched up the Alderman Library chain of command, across to the president’s office in Pavilion VIII and eventually over to the University of Virginia Police Department. University counsel Neill H. Alford Jr. (Law ’47) placed the call at 2:30 p.m. Dec. 17, more than four months after the Stella turned up missing, according to a chronology in the investigative file. In a 1976 postmortem of the events, published in an academic journal, Berkeley noted that police “were highly critical of the fact that we had delayed so long in bringing them into the case.”

The investigative file shows that the Virginia State Police and Federal Bureau of Investigation also pitched in, though UPD took the lead. The Charlottesville Police have no record of involvement, though Alford had sent a letter to the local prosecutor, telling him on Dec. 19, “I … wish you to know of our difficulty.”

An Easy Walnut to Crack

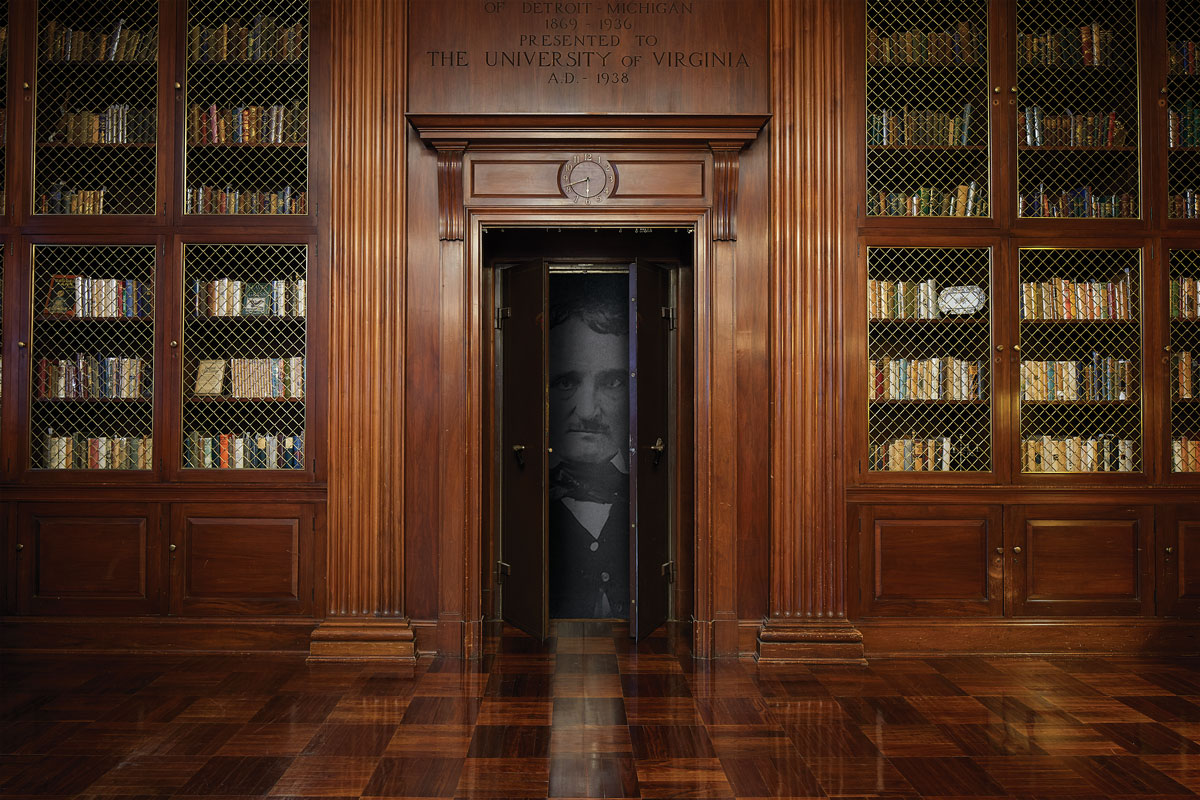

A classic whodunit needs a setting akin to an English country manor, and Alderman Library more than obliged in providing the McGregor Room as the scene of the crimes. When UVA landed the much-coveted 12,500-piece Tracy W. McGregor Library collection, announced at the opening of Alderman Library in 1938, the gift included money to finish a 2,700-square-foot second-floor reading room in style. Students today call it the “Harry Potter Room.”

Floor-to-ceiling book ladders run along brass rails, high above overstuffed leather chairs, Oriental rugs and the antique desk of the room’s then-newly deceased Detroit philanthropist namesake. The woodwork must have felled a walnut grove, from the parquet floors to the bookcases to the frame around the portrait of McGregor carved into the fireplace.

Inside this temple to book collecting sits the walk-in, two-level, 920-square-foot McGregor Room vault, at the time the sanctum sanctorum for UVA’s great literary and historical objects. To enter required overcoming, first, a set of 2-inch-thick Diebold Safe & Lock Co. armored doors, operated by a combination wheel that went up to 100 and a pair of levers the size of ax handles. But that only got you as far as a second set of metal doors, these requiring a key.

It didn’t take UPD Investigator Eric W. Shoemaker long to solve the mystery of how a thief could have surmounted the seemingly insurmountable. Practically everyone he interviewed knew the combination to the first set of doors or how to get it: It was kept on a sheet of paper in a department secretary’s desk drawer, according to his report in the file. One employee told him she learned the magic numbers within hours of starting in the department as a student assistant. As for the key to the second set of doors, Shoemaker learned it sat in a tin, unlocked, on a bookshelf, just to the right of the vault.

If it didn’t lessen their shock, it at least explained how it was that workers, dispatched to the scene two days after Alford called in the crime, found both sets of vault doors wide open, all the lights on inside and, as the saying goes, nobody home. After instituting some immediate measures, the University conducted a more comprehensive security evaluation a few months later, according to the UPD file.

If you’re UVA in the mid-1970s, you don’t call in Pinkerton or ADT. Instead, you turn to psychology professor Raymond C. Bice Jr., he of the famous “Bice devices”—homemade gadgets that packed his Psychology 101 lectures. He’d call students up to the front to don one of his sensory-distorting contraptions to demonstrate how the brain can play tricks with perception, often to comic effect.

Bice is said to have improvised with Chevy radiator hoses to repair the original carillon in the University Chapel. It was Bice who maintained the Lawn’s final exercises sound system during the era (up until it famously cut in and out and then in again, just in time to broadcast then-Vice President George H.W. Bush’s words of inspiration to the Class of 1981: “Can’t someone get this goddamned thing fixed?”).

So it was, upon the discovery of rampant looting, that the University called upon its resident MacGyver to rig up the McGregor Room vault’s first alarm system, which then stayed in place for at least the next several years.

Without a Clue

Shoemaker and the UPD investigative team faced a number of challenges. The trail was stone-cold before they started. Even leaving aside the initial delay in alerting police, it was uncertain when many objects had last been seen, widening the time frame by months if not longer.

There was no physical evidence of a crime; security was such that a thief didn’t need to break and enter. That created problems when the University attempted to make an insurance claim. University officials estimated the loss at $100,000, of which they sought $51,000, presumably because of the policy’s deductible. The insurance company rejected it, citing the policy exclusion for a “mysterious or unexplained disappearance”—in effect saying it’s not enough to claim you simply can’t find something. Eventually the company offered $25,500, though no University records could be found to show how the claim ultimately resolved.

The library staff apparently took some heat for not cooperating more fully with the legal office as it tried to put forward a stronger insurance claim—and for clinging to the hope that the items might turn up on their own. The tension prompted University Librarian Ray W. Frantz Jr. to reassure the provost in a December 1974 letter on behalf of his team, “We have no recollection of understating the possibility of theft.” Frustration with a lack of full library staff cooperation is a theme that runs through the police file.

An Inside Job

The lack of a discernible pattern in the missing items and the uncertainty of the time frame of their loss prompted Shoemaker to consider that he may be looking for multiple thieves acting independently, one keen on the Poe collection and a separate group pocketing famous manuscripts and autographs. The prevailing theory under either scenario was that it had to be an inside job, the act of people who knew their way around the vault.

The suspicion took its toll on the staff, Berkeley noted in his journal article: “The personnel of our two departments inevitably wondered about each other, and the resulting tensions hurt morale.” UPD’s requests for polygraphs compounded the angst. “We each had the theoretical right to refuse to take the test, but as you can imagine, the pressure to submit to it was compelling,” he wrote. Those who acquiesced—20 of 22 staff members—all passed the lie detector, Berkeley and Stauffenberg included.

The journal article also includes this curious observation: “It took many months for morale to recover. But when no one was arrested, the staff began to relax.”

Shoemaker’s suspect as the Poe bandit was a graduate instructor on staff who had declined the polygraph and in his police interview seemed evasive and overeager to direct suspicion elsewhere. When asked if he knew of anyone on staff who had traveled outside the country, he kept mum about his own trip to Rome in December 1973. Rome was significant because the suspect had studied at the Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies there several years before, when a series of rare book thefts occurred, “a little here, a little there,” according to a UPD source.

The then-former staffer came under scrutiny again in spring 1976, when UVA’s rare books secretary found a link between him and George Brown Davis, the Virginia Military Institute librarian who had just been arrested for thefts from that collection. According to investigative notes, the secretary had turned up an old letter in which the UVA suspect had written to Davis, “We still have an ‘attic’ full of duplicates up here which we must dispose of.”

Davis would plead guilty to having stolen 7,500 books from VMI over several years. A pleading mentions his having also raided the UVA library, though the voluminous inventory in the criminal file doesn’t list any of the missing UVA works from 1973 nor any items nearly as valuable.

The UVA suspect was never charged and has since died.

For his theory about a ring of opportunists, Shoemaker focused his suspicions on three people: a library worker in her 20s (variously described in the file as “attractive,” “exotic” and “hippy-type”), who seemed the fascination of nearly every co-worker; her friend in a different department, a man not universally liked; and their mutual friend, with whom the woman may have lived for a time, a local drug dealer stabbed to death in Florida in October 1973, as the thefts had begun to come to light.

The woman quit the library in July 1973, the month before the first discovery of something missing, moving west without paying her final rent. She agreed to an interview with her local police chief, arranged with the help of the Virginia State Police, in December 1975. She denied any involvement in the library thefts and, according to the chief’s summary, said the drug dealer had never asked her to steal for him. She initially agreed to a polygraph but later declined on advice of counsel.

The man from the other department gave at least two police interviews, one to Charlottesville authorities, who had arrested him on drug charges the following year, and another a month later to Shoemaker and UPD’s Sergeant J.H. Batten Jr. The suspect denied involvement in the heists but admitted that the three friends had discussed how easily someone could steal from Alderman Library’s priceless collection.

When the information about the thefts first reached the president’s office and the Board of Visitors in December 1973, the administration chose to publicize the losses. It meant drawing unwanted media attention and, in a matter of days, at least one scathing state editorial decrying the lack of security. Still, it was a way to elicit leads and make it more difficult for anyone to traffic in the stolen items. It also courted the risk that a frustrated thief might destroy them. If these were the acts of a disgruntled employee, that may have happened anyway.

The Cold Case Gets Colder

Nearly 50 years later, it’s the artifact of the original investigation that has all but disappeared. The FBI, which circulated bulletins to all its field offices and conducted interviews, told Virginia Magazine it had destroyed its files in accord with its record-keeping practices. In response to a similar Freedom of Information request, the Virginia State Police says it possesses only summary information, nothing substantive. UPD lost contact with lead investigator Shoemaker some time ago and was unable to help locate him. Batten and UPD Director W. Wade Bromwell, who also worked the case, have died.

Berkeley, the manuscripts curator, retired in 1999. He declined to be interviewed about the thefts, deferring instead to his memorandum rather than try to recall details so many years later. The cataloger Stauffenberg, who initially discovered the Stella missing, also declined to be interviewed about the events.

Since the 1970s, UVA’s rare holdings have multiplied in number. They include what’s still considered one of the world’s foremost collections of Americana. After the opening of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library building in 2004, and with it the introduction of more sophisticated security, the McGregor Room vault has become little more than a walk-in storage closet.

Throughout these events, Edgar Allan Poe’s student room has sat quietly across the street from the library. The window in No. 13 West Range used to include a pane with a verse Poe was said to have etched into it before debt and disgrace forced him to leave the University. The glass eventually broke, but the pieces have been reassembled inside a picture frame. Special Collections stores the curio in its modern archives, inside a gray cardboard box. Perhaps the shards of wisdom deserve more prominent display in the McGregor Room, on a walnut shelf, just to the right of two sets of armored doors:

O Thou timid one, let not thy

Form rest in slumber within these

Unhallowed walls,

For herein lies

The ghost of an awful crime.