Soldiers’ Stories

Alumni talk about a life of combat

For many Americans, military life is an abstraction, something that takes place behind a walled base or in another country. Our notion of the war in Iraq is often cobbled together from images on the evening news of roadside bomb explosions, flag-draped caskets and tanks rolling through expanses of sand in every shade of brown. On March 19, the nation marked its fifth year of conflict in Iraq. Days later, a more sobering milestone was reached: the 4,000th U.S. soldier killed in action there.

Most of us have scarcely a clue about what a soldier’s day-to-day life is like. While you may not know what it’s like to interrogate an insurgent or jump out of bed at 3 a.m. and don a gas mask, some of your fellow alumni do. In recent years, an average of 45 to 70 graduates each year from UVA’s ROTC programs entered military service. Still more alumni join up later.

The Virginia alumni serving in Iraq are not just infantrymen and aviators fighting insurgents, but also chaplains, physical therapists, doctors and administrators taking care of their own. They are engineers and civil affairs officers helping to rebuild Iraq. We contacted a handful of them—some of whom are in Iraq, others who have gone and returned—and asked about their experiences.

The stories that follow are a window into the combat lifestyle. Most military men and women in Iraq work seven days a week for months on end, separated from their families. Those who served in the early days of the war often lived in tents, bombed-out office buildings, even Saddam Hussein’s palaces. They went months without a proper shower or truly clean clothes, often in triple-digit temperatures. Few voiced any complaints.

“I have the best job that any man could ask for,” writes Army Major Cris Simon (Col ’95) by e-mail from Iraq. “I get to wake up in the morning and do something I believe in. Frustrating sometimes? Absolutely. Do I think that it’s worth it? I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t.”

James C. Balserak (Col ’86)

Colonel, Tucson Air National Guard

In Iraq: Sept.-Nov. ’04; May-Nov. ’07

The majority of cases we saw were everyday ailments, things like back pain and sore throats. But another part of our job was going down to the Army morgue and processing the paperwork for soldiers killed in action. We handled about 80 to 100 American and coalition service members who were killed in action every month.

I’m a trauma surgeon in Tucson and I see a lot of civilian trauma—gang violence injuries, automobile accidents. When you see a U.S. serviceman or servicewoman in military uniform with horrific dismemberments and burns, it affects you in a different way. The first killed-in-action soldier I saw had been hit by an IED and his body was completely burned. I could barely recognize him as a human being. In his pocket was a picture of him with his wife and child. I was thankful they would never have to see him like that.

It’s particularly rewarding when you know that you’ve saved someone’s life. In November 2004, we had eight critically wounded soldiers come to us and we were able to save seven of them. They were on an orientation ride in the area and they walked over to inspect something suspicious. It turned out to be an IED and it detonated. When they arrived at our medical facility, the back doors of their armored personnel carriers dropped down and it was like a scene from a movie: critically injured men falling out with blood everywhere. We train and train and think nothing like that is ever going to happen. The medical staff functioned amazingly well. We couldn’t have saved Specialist Baker, the fellow who lost his life. He had suffered severe injuries to the head and torso. The sad thing was that it was his third day in Iraq. Seven days after he died, his wife gave birth to twin boys.

Seeing all of that, I came back feeling a little different. But the experience was very rewarding. I’ll probably go again.

Balserak is a general surgeon and senior partner with Southwestern Surgery Associates in Tucson. He is also an associate clinical professor of surgery at the University of Arizona and commander of the 162nd Medical Group, Tucson Air National Guard.

Frank J. Snyder (Engr ’92)

Major, Army

In Iraq: Aug. ’03-March ’04; Oct. ’05-May ’06

When you’re working 18 to 20 hours a day for 220 straight days, time moves very quickly. There’s no end to what needs to be done and there’s no time off. I recall the one time I tried to go to church with a buddy of mine. Something happened and my boss sent someone to the chapel to bring us back to work. I think I lost 15 or 20 pounds in seven months just from the pace of life and the heat.

But at times, it’s amazing how quickly time can grind to a halt. I remember being out on a convoy at 2 or 3 a.m. going from Baghdad to Balad. Three kilometers ahead of us, the night sky lit up twice, indicating an IED strike. The convoy ahead of us had been smacked. We got there a few minutes later, and they’d set up a cordon. We had to stop until the area could be inspected. The process took about three hours.

We were on a road far from an American base, and looking to the left and the right, there was nothing but dark empty desert. We were just sitting there in the middle of the road, completely vulnerable. Anyone could creep up and fire an RPG. The technique I picked up is to completely dissociate from the rest of the world and assume I’m already dead. If you don’t, you’ll be constantly fearful. Assuming the worst had already happened made those times bearable.

Snyder is stationed at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. From there, he travels worldwide to train units preparing to deploy to Iraq and Afghanistan.

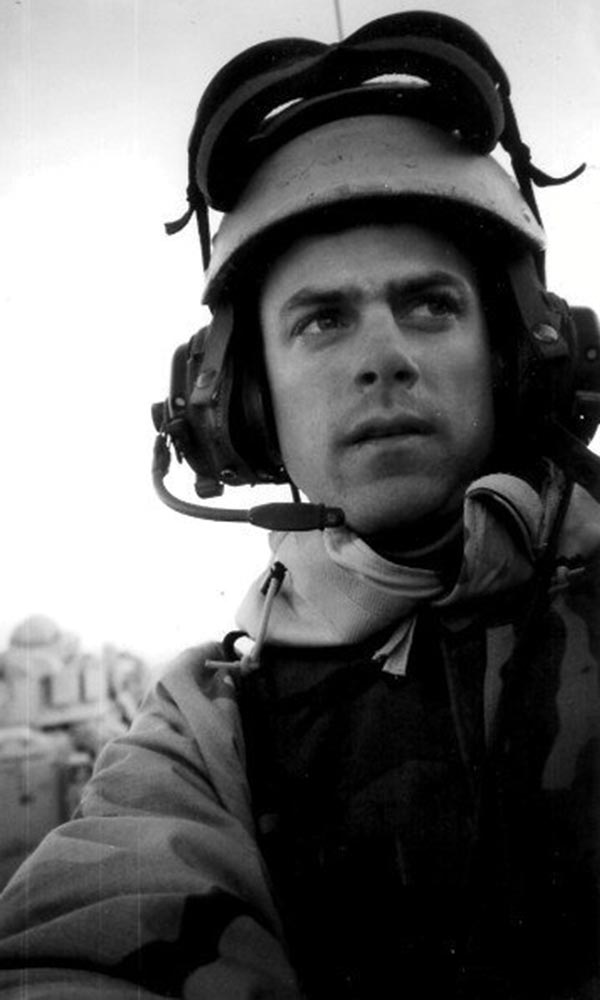

James P.L. Holzgrefe (Engr ’00)

Captain, Army

In Iraq: March ’03-Feb. ’04; May ’07-present

The invasion in March of 2003 was a really intense time. We spent about two weeks in Kuwait prior to invasion planning, training and getting acclimated to the environment. I was a platoon leader at the time, in charge of four helicopters, 10 pilots and six crew chiefs. Kuwait was pretty miserable. It was hot, sandy and windy. I’ll never forget the night of the invasion. We were on the airfield readying our aircraft and trying to cram a couple of days’ worth of water and food into every available spot. We had become accustomed to occasional missile attacks with the accompanying Patriot launch. You would hear an explosion, then an alarm would go off and everyone would put on their gas masks and move into protective bunkers. That night was the first time any of us had actually seen the Patriot launch and intercept something. It seemed to be overhead, but was probably several miles away. We went through the normal drill, but the sight of it added to the intensity of the moment. That was the same night as the fratricide grenade attack by Sgt. Asan Akbar at an adjacent camp. I think we were all ready to get out of Kuwait at that point, even if it meant going into Iraq.

Holzgrefe is currently the chief operational planner for the 3rd Squadron, 17th Air Cavalry Regiment, in Baghdad.

Geoffrey P. Fiutak (Arch ’89)

Major, Army

In Iraq: March ’03-April ’04

I worked in civil-military operations, and our goal was to create or improve all of Baghdad’s municipal institutions like hospitals, schools, banks and fire departments. War aside, Saddam hadn’t maintained the city’s infrastructure—it was already falling apart. Throw in insurgents, corruption and everyday crime, and it became quite a project.

We were dealing with a local culture very different from ours. When we invaded, Iraqis were used to living under Saddam’s dictatorship, where they did what they were directed to do. There wasn’t much need or opportunity to take initiative. We could put out garbage dumpsters at the end of each neighborhood block, but we’d come back and the street would still be filled with garbage. It would go into the storm sewers, plug them up, and then we’d have huge backups of sewage. All of a sudden, the international news is broadcasting that we’re not taking care of Sadr City—look at the sewage! It was a process of educating Iraqis and getting them to take responsibility for their community.

Having seen what a good faith effort so many Iraqis and Americans have made, it’s frustrating that we can’t look back on it now and say, “Look how much better everything is.” We got the feeling while we were there that it’s definitely going to take a while. As in Kosovo, we’re dealing with ethnic groups who have deep-seated historical hatred for one another that existed long before the Americans arrived. It’s going to take a while to move past that and get the next generation of Sunnis and Shias and Kurds to see that working together is the best option.

Fiutak is a senior architectural planner at C&S Companies in Syracuse, N.Y.

Seth W.B. Folsom (Col ’94)

Major, Marine Corps

In Iraq: Feb. ’03-May ’03; Feb. ’08-present

On April 3, 2003, during a routine reconnaissance mission along the Tigris River, my company was ambushed by a platoon of enemy fighters from the Fedayeen Saddam, a group of paramilitary fighters who reported directly to Saddam Hussein. Although the war had been waging for two weeks, it was the first time my Marines and I had come under direct and intense enemy fire. Any fears I might have had that my men would not respond appropriately vanished as they unleashed high-explosive hell on the ambushing enemy soldiers.

The dust blanketing our vehicles flew off in sheets from the concussion of our 25mm cannons, and the impacting high-explosive shells twinkled like Christmas tree lights against the enemy positions. Our cannons roared with an ear-splitting “thump, thump, thump” sound, and the sparkle of empty brass shell casings littered the ground around us. The dirt splashed in great black geysers from incoming friendly fire, splintering the trees like giant toothpicks. My face burned from the heat of rocket exhaust as Cobra gunships that had flown to our rescue fired rockets from 50 feet above my vehicle. The tree line that hid the enemy fighters was aflame. Throughout the firefight, time periodically seemed to slow to a crawl and then suddenly speed up. It was pandemonium, chaos. Days earlier one of our Marines had been killed after he stepped on an errant cluster bomb. This combat felt like the controlled fury of men avenging the death of their comrade. But for me it was also exhilarating; my men were doing what they had been trained to do, and they were doing it brilliantly.

When the guns finally went silent and my platoon commanders reported in to me that everyone was safe and that the enemy had either been routed or destroyed, I felt a visceral satisfaction unlike any I had ever known. Everything my Marines and I had trained for in the previous months and years had been actualized in that one moment, and in our trial by fire, Delta Company performed magnificently.

Folsom is currently serving as the team leader and senior adviser for a military transition team in Al Qa’im, Iraq. He is the author of The Highway War: A Marine Corps Company Commander in Iraq.

Kimberly “Kimi” White (Col ’02)

Captain, Army

In Iraq: March ’03-Feb. ’04; July ’05-Nov. ’05

During my first tour of Iraq, I led a construction platoon in the Army Corps of Engineers. One assignment sent us out to the Turkish border. The town’s wells weren’t deep enough to draw enough water for the town, so the town relied on water delivery trucks to bring water in from the mountains and sell to the townspeople water at insane prices. Our mission was to dig a water main several miles from the mountains, out to the villages.

I became used to Iraqis staring at me on the street. Frequently, a woman would gawk at me, walk away and return with her daughter or granddaughter, gesturing as if to say, “Holy cow—a female soldier!” While digging the water main, the town’s children liked to watch our progress. They had the same reaction—“A woman!” One little girl saw me and ran to tell her mother. Out in the heat digging a trench, I was hardly at my most feminine. Wisps of hair escaped from my helmet and whipped around in the wind. We didn’t have shampoo or constant access to bathing water, so my hair was a mess. The mother came out and brought me two little silver barrettes to hold my hair back. They had to be the most expensive thing she owned. I was so touched—I still tear up when I think about it.

White is in law school at George Mason University.

James N. Blain Jr. (Col ’96)

Major, Army

In Iraq: March ’03-March ’04; March ’05-March ’06

I was a company commander stationed near Saddam’s hometown of Auja, south of Tikrit. We weren’t there by accident: We were searching for Saddam, among other things. One way we did that was to build relationships with the local sheiks. It takes an elaborate dance to build relationships with Iraqis of power. They didn’t immediately respect us or want to help us. We all had objectives: We wanted to know where the bad guys were and find out where and by whom we might be attacked. We equally needed each other’s cooperation to provide electricity, running water and other public services for the people. For them, we could be a source of security, money and influence for their tribe.

Arabic ways of building relationships are utterly unlike ours. They greet you with a kiss on either side of your face. They value personal relationships and will get very close to your face when they talk, even though they’re speaking Arabic and we’d have to wait for the interpreters to translate. They wanted to see our expressions and read us. A lot of times they speak English, but they don’t want to reveal that. It’s part of the game.

After you get to know them for a while, they would throw you a feast. In attendance would be the police chief, the mayor, the sheik, his sons, maybe his brothers, the male servants and other assorted guys in elaborate sheik garb. We never saw any women. They’d slaughter a lamb and praise Allah. These feasts were a big deal to them and were their show of wealth. While eating, the Iraqis would pick the food off the hot carcass and put it on the plate for you with their hands. You’re standing around the table eating. You eat with your right hand—just ball up the meat and the rice and stick it in your mouth. If your plate is empty they’ll serve you more. If you want to stop eating, you literally have to put the plate on the ground, walk away and wash your hands. After the meal, we would smoke cigarettes (I don’t smoke, but I did anyway) and drink hot, sweet tea … that’s when most of the important negotiations occur.

The meetings I attended didn’t usually get accurate info about Saddam, although I never directly asked other than to remind them of the possible $25 million they could earn if their info led to his capture. The sheiks were more scared of him than they were of us. But my brigade did catch him. One of the platoons I commanded was guarding the Tigris River nearby during the operation, making sure he didn’t escape by water. When they got him, my brigade commander called us and congratulated us. We all thought, “Do we get to go home now?”

Blain is studying at the Army’s Command and General Staff College at Fort Belvoir in Alexandria, Va.

Bryan K. Turner (Col ’83)

Lieutenant Colonel, Virginia Air National Guard

In Iraq: Oct. ’90-April ’91 (Desert Shield/Desert Storm); Sept. ’03-Nov. ’03

The day before the ground war began in 1991, I was piloting one of four F-16s flying together. Our job was to bomb a Republican Guard encampment on the Iraq/Kuwait border. As we were preparing to attack the target, an emergency call came in. A team of Army Special Forces troops had covertly made their way into Iraq before the invasion and had already reached a site 50 miles south of Baghdad. We had no idea there were U.S. forces that far deep into the country before the ground war. The problem was that Iraqi kids had come across their covert hold-up site in a field. The eight-man special ops group was taking fire from hundreds of Iraqi troops. Our four aircraft were the first U.S. assistance to reach them. We dropped bombs to take out the Iraqi troops and their trucks. We stayed until the next set of F-16s arrived to take over. That whole sequence repeated for the next six hours until helicopters came and were able to emergency extract those guys from the middle of the country. We were able to stop the initial wave of Iraqis trying to capture them. Hours after we got back, we learned the special ops team had been extracted and all had lived.

That Christmas, each of us got a letter from their squad chief leader with a picture of the eight guys, taken on the day they went out on that mission. The letter thanked us and said they wouldn’t be home for Christmas without us. I’ll always remember that. It’s probably why I still do this job.

Turner is the operations group commander for the Virginia Air National Guard’s 192nd Fighter Wing at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia.

Lara Yacus Chapman (Col ’05)

First Lieutenant, Army

In Iraq: Jan. ’06-Dec. ’06; March ’08-present

One particularly rewarding job I had was being the officer in charge at the main gate to Camp Taji. My unit was responsible for screening all of the traffic entering the base—pedestrians and vehicles, U.S. and Iraqi.

Being at times the only female U.S. soldier at the gate, it often fell to me to search Iraqi females for contraband and suicide bomb vests. It was a little scary the first few times because their clothes are loose and flowing, and hiding explosives on women is a known terrorist tactic. The first woman I had to search was crying profusely because her husband had been detained for suspected insurgent activity. She was coming to the base to find out what happened to him. She had two young children with her, a dirty but adorable little girl about 3 years old and a boy of about 6. They were sweet, innocent children, and a little shy to be around an American soldier—and a female one at that. I smiled and waved to them and the little girl soon decided she could stop hiding behind her mother. The next time they came through the gate, the children remembered me and were full of smiles. I always made sure to bring out bubbles or little toys for the kids. She was just an average Iraqi woman who was concerned about her family. Without her husband at home working, she and her children were at risk and didn’t have the income they needed. I really felt for her, but at the same time, it was sobering. I had no idea what her husband had done. Had he been involved in the deaths of soldiers that I knew?

Chapman is currently a company executive officer at Camp Prosperity in Baghdad.

John T. “Hap” Arnold (Engr ’88)

Lieutenant Colonel, Air Force

In the Middle East: Sept. ’04-Jan. ’05

I helped run the air war for Iraq from the Combined Air Operations Center in the Middle East. From the operations floor, there are giant screens that show all current operations, including every airplane flying in the region and tons of feeds from the global information grid. From my desk I had screens I could use to contact anyone involved in moving air power. A public affairs officer would sit to my right so that he could deal with the media and a lawyer sat on my left.

It’s amazing how the media got things wrong. The bad guys will feed the media information saying we killed two moms and six babies when, in reality, the Predator video feed shows nothing. The Air Force does a great job of doing whatever we can to minimize collateral damage.

It’s a shame that the media focuses so much on death and roadside bombings when there are so many positive things happening in Iraq. Schools, water lines, power grids, hospitals—it’s all been built or being built. Everything that we take for granted in the States is being developed or nourished in Iraq to be an example of democracy in the Middle East. It just takes time. Nation building is a very slow process.

Arnold is the commander of the 36th Electronic Warfare Squadron at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida.

Cristian J.T. “Cris” Simon (Col ’95)

Major, Army

In Iraq: June ’05-Aug. ’06; Sept. ’07-present

The saying is “a sound mind in a sound body”; I joke with my fellow officers that if you can’t have one, you might as well have the other. Mission permitting, we hit the gym for at least an hour daily. The real sanity-saver, though, is communication from home. The pictures and videos my wife e-mails me from the States are particularly awesome. My son, Daniel, is 1 year old and you can’t imagine how bittersweet it is to know he’s growing up on the other side of the world. The USO has a great service where they burn a DVD of us reading children’s books and then they send the DVD and book free of charge to your home. That way I get to read stories to my son. My wife tells me that Daniel knows my voice and when she puts the DVD in, he will say “Da-da.”

Working through some local orphanages, I’ve had the opportunity to set up some clothing/toy drives supporting Iraqi children. Children arguably suffer the most in war. One translator relayed to me the story of a little girl I saw, maybe 5 years old, who had no shoes and no smile. He told me that she hadn’t smiled since her parents were killed in front of her with a knife by al-Qaida. Their crime? They had been accused of “assisting the Zionist occupiers.” Knowing that I can do something to make kids’ lives a little better is deeply rewarding; maybe it has something to do with the fact that my son is so young. To be able to say to a child, “There is someone on the other side of the world, someone you will most likely never meet, who loves you and wants you to have this toy/jacket/blanket”—it almost gives one hope for the future.

Simon is a logistician for the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) in Balad, Iraq.

Ryan P. McDermott (GSBA ’08)

Captain, Army

In Iraq: March ’03-Aug. ’03

I was a platoon leader in the 3rd Infantry Division during the assault into Iraq in 2003. We were responsible for reducing obstacles and destroying enemy forces from the Kuwaiti border all the way to Baghdad.

On April 2, we attacked through the Karbala Gap and raced north to seize a key bridge across the Euphrates River that would later serve as the Army’s primary avenue of approach into Baghdad. My platoon was the first unit to assault across the bridge, which was damaged by the Iraqis in their attempt to blow it up. We defeated forces of the Iraqi Republican Guard at the bridge while successfully securing and defending the far side.

The following day, my unit was tasked with securing Saddam Hussein International Airport. En route to the airport, we again met enemy resistance and engaged with decisive force. We arrived at the airport gate as it turned to nighttime. There was Iraqi anti-aircraft fire lighting up the sky all around us. The Iraqis were clearly expecting an air assault. They didn’t expect ground troops to reach Baghdad that quickly.

It was pitch black and we couldn’t find a clear entrance to the airport. There’s an urban legend that a tank can blow a hole through a wall big enough to drive through. We tried it—doesn’t work. But in the process of blowing the hole in the wall, a tree caught on fire and illuminated the entrance. My platoon led the way onto the airport tarmac. All the while, the war continued 360 degrees around us. Friendly rockets were firing over our heads and Air Force bombs could be seen in the distance. The final battle at the airport was one-sided. After three straight days of fighting to Baghdad, we were finally able to get some real sleep.

McDermott graduated from the Darden School of Business in May and joined Lehman Brothers in New York City as an associate in its investment banking division.

Kimberly Barkley Decker (Col ’04)

Captain, Army

In Iraq: Feb. ’05-Jan. ’06

Being in Iraq has had such a positive effect on my life since I’ve been back home. It’s made me realize how many good things take place every day, things I might have otherwise taken for granted. I’ve learned to appreciate the luxury of an afternoon nap, or being able to see my family every evening. Doing housework feels more like a privilege—I actually have a house to take care of. At the very least, I appreciate not breathing in sand all the time.

In our health care system, any civilian can go into any doctor and hospital and expect high-quality care. When you’re an Iraqi citizen, you might not have that same expectation. I’ve been to Iraqi hospitals that didn’t have a whole lot in the way of equipment, supplies and trained staff.

My husband was deployed with me in Iraq and I appreciate every day that he’s no longer in the line of fire. In Iraq, we would eat dinner together when we could, but we lived separately with our units. We had been separated so much that when we came home and had the chance to live together and function like a normal married couple, we found our marriage strengthened quite a bit. We went through similar experiences, and we can talk about them and feel understood.

There were definitely days in Iraq that I literally had to put one foot in front of the other and think about the next hour rather than the rest of the deployment. But something that was such a challenge at the time ended up being so positive. I learned a lot about myself and about the world. I got to see history being made right in front of me.

Decker is the chief of personnel at Irwin Army Community Hospital at Fort Riley, Kan.

Brian T. Watkins (Com ’95)

Major, Army

In Iraq: Jan. ’04-Feb. ’05

The most rewarding thing for me was being able to fly on Iraqi election day at the end of January 2005. These were Iraq’s first fair and democratic elections in more than 50 years. It was rewarding knowing that people were going to be able to use their voices to determine what their government would look like. In Baghdad, the government restricted vehicle movement that day, so throngs of people walked to their local polling stations to cast their votes. It was weird to fly over the streets and see no traffic except for U.S. and Iraqi security forces. Fortunately, there were very few incidents of violence that day.

Our primary mission in Iraq was to fly our OH-58D Kiowa helicopters and look for insurgents who were causing problems, work with coalition and Iraqi ground forces to capture them and deter future insurgent activity. When you’re so focused on the negatives—not the positive things like the rebuilding effort—it can be tough on morale. Watching the Iraqis vote on election day was a good reminder of why we were there.

In June, Watkins will graduate from Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas and rejoin the 25th Combat Aviation Brigade at Wheeler Army Airfield in Hawaii.

Paul D. Hicks (Engr ’96)

Major, Army

In Iraq: April ’03-March ’04; Dec. ’04-June ’05

When I left for my second tour in Iraq, my wife, Kim, was not only left to take care of our two children, ages 3 and 2, she was also pregnant with our third child. I took the job with the understanding that I’d be home before my wife gave birth.

On my first tour, I was lucky to call my wife once a month. On this tour, I had a phone on my desk and could call every day. Because of the time difference, I usually called around 1:30 a.m. Baghdad time, which was 6:30 p.m. in Richmond, Va. It was two weeks before Kim’s due date and I was preparing to fly home in a couple of days. When I made my nightly phone call, Kim’s father answered the phone, which was not at all normal. He started yelling congratulations and said something about Kim having the baby. I was completely disoriented. I thought he was joking. Turns out he wasn’t.

I hung up the phone and looked around. When you discover that you have a new baby, you want to tell somebody, but it was 1:30 a.m. and I was alone. Just then, one of my colleagues walked in. The shock was all over my face. We sat down and shared that moment. It was really special. A few days later, I met my daughter, Evelyn.

Hicks is currently an intelligence officer with the Defense Intelligence Agency in Washington, D.C.

Kenneth J. Schmidt (Col ’76)

Lieutenant Colonel and Chaplain, Army Reserve

In Kuwait: Dec. ’04-Dec. ’05

In Kuwait, I led a chaplain detachment which ran four chapels. As we were shutting down Camp Doha, we had to clear out an enormous volume of supplies from the chapel. People in the States had donated all kinds of food and printed materials for Jewish officers. Every year we’d get a shipment of Seder kits containing everything you would need for Passover in a little box. There was a bowl of matzo ball soup and a portion of gefilte fish, matzo, a Seder plate and a prayer book. The thing was, we didn’t have any Jewish officers at the time. We had an entire room crammed floor to ceiling with Passover supplies—hundreds, maybe thousands of Passover kits. Even if we had Jewish personnel, it was far more than they could ever eat. We couldn’t figure out what to do with it all.

One of my sergeants speaks Spanish, and one day a Salvadorian general walked over and started telling her about his problem. Most coalition countries give their troops in Iraq the best of everything, but this unit of 300 Salvadorians had nothing. They landed in Kuwait with one pickup truck to get them to Iraq. They were living on one MRE a day. The general wondered if we had any Spanish Bibles. The sergeant gave him everything we had in Spanish and then had a thought: “You guys need some food?” She loaded them down with Passover kits. The next day, their commander came back in tears. “Thank you thank you,” he said. “That was the best chicken soup we ever had. Nobody has ever been so generous to us.”

Schmidt is serving full time as a mobilized reservist attached to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg in North Carolina.

Lauren Makowsky Wolfe (Col ’01)

Captain, Army

In Iraq: Feb. ’03-Feb. ’04; July ’06-Sept. ’06

When I went back in 2006, the amenities on base were excellent. We had trailers to live in, showers, gyms and a range of food options, including fresh fruit and pastries. But back in 2003, our living conditions were comically bad.

It was miserably hot—in the summer it could reach 120 degrees by midday. Our 20-pound bulletproof vests would hold the heat in. We took water bottles with us on convoys, but very quickly the water would reach the temperature of hot tea or coffee. We’d try to wrap wet socks around us to keep cool, but it was hopeless. No one had air-conditioning.

I was a platoon leader in an infantry brigade, and we were sleeping in sleeping bags under the stars for a couple of months. We finally did get tents, and I lived with one other lieutenant, the only other woman in the unit. We had an interesting time trying to keep the tent clean. Rats frequently ran through, attracted by food and warmth. We’d also find huge spiders and scorpions. My tentmate happened to look under her pillow one night and found a six-inch centipede curled up.

We didn’t have showers for the first five months, but luckily I had brought a camping shower bag with me. When we did get a shower tent, it wasn’t exactly refreshing. There wasn’t a drain, so you’d be ankle-deep in dirty water and sand.

One night we were sleeping in the tent when a dust storm came through. Before our tent crashed down—all of them did—I remember us looking at each other and saying, “How did we get into this?” Orange dust coated everyone and everything. The bugs in the sand were now flying through the air. We wore goggles and scarves to try to keep the sand out of our eyes and mouth, but it got in both places anyway. We coughed up dirt for a couple of days afterward. The storm shut down operations completely for about 18 hours. There was zero visibility. It was surreal.

Wolfe is an assistant regiment intelligence officer at Fort Campbell in Kentucky.

Robert A. Willis (Engr ’91, ’01)

Lieutenant Colonel, Army

In Iraq: Jan. ’05-June ’05

Military experimental test pilots fly and evaluate new aircraft, weapons and systems, and recommend whether the service should procure them or not. As the war progressed, it became apparent that the test pilots, who work primarily stateside, had trouble keeping current with the evolving tactics with which to evaluate all the new equipment. In 2004, I pioneered a program to embed test pilots into deployed combat units in Iraq and Afghanistan. I made myself the guinea pig and deployed to a base on the north side of Baghdad.

For more than 16 years, I have had the privilege to fly the incredible Apache attack helicopter. In Iraq, a typical night mission would find us patrolling for insurgents planting roadside bombs (IEDs). Using our infrared night-vision cameras, and frequently flying at relatively high altitudes, we would see them in the pitch dark with their shovels and wheelbarrows, and they wouldn’t see or hear us. Sometimes, we would radio the coordinates to the Army guys controlling the unmanned planes to get a second look. If confirmed, we introduced them to a laser-guided missile.

Don’t misunderstand my tone—I’m not an inherently violent or aggressive person. I don’t have guns in my house. I don’t drool over war movies. I’m a classical pianist and cellist and, like many officers my rank, I have several advanced degrees. I love spending time with my wife and daughter. But I have no regrets for how we dealt with the IED insurgents. They are the worst of the worst over there, and it seems every time you turn on the TV, you hear that another handful of Americans or Iraqis were victims of an IED. In most other combat situations today, the decision to fire on the enemy is more complex, but killing the insurgents placing IEDs is somewhat unemotional and straightforward.

Willis is an experimental test pilot at the U.S. Army Aviation Technical Test Center at Fort Rucker in Alabama.

Paul J. Froehlich (Educ ’03)

Captain, Army

In Iraq: June ’07-present

When we’re not working, everyone here seems to have their personal choice of entertainment, whether it’s books, the Internet, DVDs or video games. A physician’s assistant and I started “Game Night” on Saturdays, and we usually have five or six people show up to play board games. Like many soldiers, I’ve spent some of my time working on an Army correspondence course.

In my room I’m able to pay for an Ethernet connection to satellite Internet. I talk with my wife via webcam every night. For everyone, there is a constant underlying stress in being separated from our families. When my father was in Vietnam, he and my mother communicated by mail that took a long time to be delivered. They agree that webcams really help.

For many soldiers, sports and exercise are their stress outlets, and also a source of pride and camaraderie. They’re very disappointed when I tell them to take it easy on the upper-body weight training until their rotator cuff tendonitis gets better, or that they should use the elliptical trainer instead of running until their ankle sprains heal. I once had a die-hard video-gamer patient with an elbow overuse injury on whose profile I had to write, “No Guitar Hero.”

Froehlich is a physical therapist with the 82nd Airborne Division outside of Nasiriyah, Iraq.

T. Westray Battle III (Col ’98)

Lieutenant, Navy

In Persian Gulf: Sept. ’05-March ’06; July ’07-Dec ’07

I completed two deployments in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom in the Persian Gulf, one each on the USS Theodore Roosevelt and USS Enterprise. An aircraft carrier is essentially a small floating city with more than 5,000 people living in extremely tight quarters. My eight-man room on the “Big E” was roughly the size of a UVA dorm room double. (I can’t complain—many enlisted personnel live in compartments with more than 60 other sailors.) It’s oppressively hot in the summertime. The flight deck is 110 degrees before you start jet engines; after 15 jets are blowing hot exhaust on a postage-stamp piece of asphalt, it reaches 130 degrees.

I primarily flew over the southeast portion of Iraq and the city of Basra, at one time controlled by the British and Australians. Whereas the region was relatively peaceful in 2005, the Brits and Australians have essentially withdrawn and Shia militia groups have taken over. Recently, with the Iraqi Army fighting Muqtada al-Sadr and his militia, the deteriorating situation in Basra has been in the news. It was disappointing to see the effects of abandoning the Iraqi people before the job is finished.

Ultimately, joining the Navy has done far more for me than I could ever do for it, and I would do it all over again tomorrow. While public support for the war has waned, nearly all the troops I served with believe they are doing something special for the people of Iraq and for the United States. It’s apolitical to them. They’re doing the best they can and making a difference every day.

Battle is an aviator, flying the S-3B Viking out of Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Fla.

Your Story

We asked alumni all over the world to send in an account of their own military experiences:

Brian A. Krakover, MD, FACEP MAJ, MC

Brigade Surgeon

82nd Sustainment Brigade

Ft. Bragg, NC

I read the article in the most recent Virginia magazine. I was actually deployed with Paul Froehlich. Small world.

I am a College/Army ROTC ‘97 grad. During my most recent deployment to Iraq I ran into CPT Dan Reynolds (Col ‘96) and CPT Mark Vagnetti (Col ‘97). I am a Brigade Surgeon and Emergency Medicine physician in the 82nd Airborne Division. I was stationed outside of Nasiriyah, in southern Iraq, but in 15 months I worked for 6 weeks in the Baghdad ER, trained Iraqi security forces in combat lifesaving skills, and logged many miles on the IED-laden roads of Iraq making sure our soldiers’ medical needs were met. I had a rare opportunity to visit the 5000-year-old ruins of the ancient Sumerian city of Ur, as well as meet many Iraqis. I also served as the lay leader for Jewish soldiers—which was especially meaningful as we were located close to the site of what is believed to be the home of the prophet Abraham for most of his life prior to his journey to Canaan.

ENS Frederick Espy (Col ‘05)

USS SAN JACINTO (CG 56)

Northern Arabian Gulf

Ever since the attacks on the Twin Towers and Washington, D.C., on September 11, 2001, it has been said that we are a nation at war. I was wearing my newly pressed naval uniform because the UVA NROTC had its Leadership Lab on that fateful Tuesday. I went to my 8:30am international relations class and then back to Dunglison dorm to relax. I turned on the television to hear the news that we had been attacked. I remember seeing Aaron Brown with the backdrop of New York and the split screen of the Pentagon smoldering under flames from the plane impact. Grasping the gravity of the event, I rushed over to Maury Hall to see if any other midshipmen knew what was going on. I went to the MIDN Lounge in the basement and saw at least ten fellow midshipmen huddled around the big screen staring in disbelief as Dan Rather attempted to tell the country about what had transpired. Video footage showed the twin towers on fire and eventually collapsing. Later in the day, our unit commander, Captain Bedford gathered the midshipmen in Maury 209 and stated bluntly that our nation was at war because we had been attacked by terrorists. He then said something that has stayed with me: “This will be a war that you and your generation will fight.”

Ever since November 2005, we have been in the Northern Arabian Gulf, either protecting the Iraqi Oil Terminals of ABOT and KAAOT or doing plane guard for the carrier, USS THEODORE D. ROOSEVELT (CVN 71). The Al Basra Oil Terminal and Khor Al Amaya Oil Terminal are critical to the welfare of the Iraqi economy; merchant tankers from all over the world come to the terminals to receive fuel. And these oil terminals make up 85% of the Iraqi economy. In April 2004, terrorists attempted to attack the terminal using small boat tactics, but were stopped before they could do any damage. However, they killed two American sailors and one Coast Guard sailor. Today, the U.S. Navy, partners with the British and Australians in conjunction with the fledging Iraqi Navy to protect the terminals and keep any enemy from getting too close.

You know it can get pretty dull up here in the NAG with constant boat operations from one ship to another, flight operations commencing every couple of hours, and the repetitiveness of going in circles in a box. One night, however, I realized we were at war.

On the night of the February 3, 2006, I went to the bridge to stand as the junior officer of the deck from 17:30-20:30. It was our 42nd and last night in the NAG defending ABOT and I knew it would be a dull watch, with only flight quarters to pass the time. When I got to the bridge, the seas were rough due to winds in excess of 30+ knots and flight quarters had to be postponed. I just kept calculating true wind in order to report my calculations to the CO so he could make a decision on proceeding with flight quarters. In addition to the typical bridge team, our ship stationed the tactical action officer (TAO) on the bridge so they could visualize their strategy for managing the defense of ABOT and controlling the tugs and tankers that proceeded to and from the terminal.

Around 19:00, the port lookout reported a dhow (fishing vessel) approaching ABOT. As the dhow started to creep towards ABOT, the TAO sent the Patrol Craft TYPHOON to shoulder the dhow out of the sectors. Due to the stormy seas, TYPHOON could not operate with all of its capabilities, so they shot a flare to warn the dhow. At that time, I was on the starboard bridge wing and I was surprised to see a bright red flare erupt against the backdrop of the night sky. I went back inside the bridge and heard the report from the TAO and radio circuits that TYPHOON was going to shoot a warning shot at the dhow because it continued to close the terminal.

The TAO yelled, “warning Shot ineffective, the dhow is still inbound ABOT, TYPHOON scram!” ABOT had decided to shoot a warning shot at the dhow, so in order to get a front row seat I went to the starboard bridge wing to see what was happening. I saw TYPHOON (its running lights) leaving the area at high speed then I watched as a round was fired towards the incoming dhow. ABOT continued to report that the dhow would not turn away and they requested permission to use disabling fire. By now we are getting ready to engage this dhow with machine gun fire that could possibly wound or kill its occupants. I was speechless as I witnessed war firsthand. I was staring at ABOT as they fired a steady stream of .50-cal and M-240 machine gun fire at the dhow. The red tracers made there way from ABOT towards the dhow, some bouncing off of the water and harmlessly into the sky, however, a few rounds impacted the dhow causing bright white sparks to fly in the air. I was in disbelief. The rounds continued to come from the Iraqi and American sailors for another 10 seconds until “hold fire” was announced. After a few minutes, the dhow headed towards ABOT again and this time TYPHOON fired about 20 rounds at the dhow causing further damage to the dhow. After these shots through their vessel, whoever was on that dhow decided to depart the area.

Because the seas were too rough to put our rhib (rigid-hulled inflatable boat) in the water, we never found out if anyone on the dhow was injured or killed. This night was a moment of clarity. Even though soldiers and marines fight every day in Iraq, what we do out here is important as well. We help keep the Iraqi economy flowing and even though we do not engage an enemy on a regular basis, we are always prepared. On September 11, 2001, Captain Bedford said that war on terrorism would affect us, and on Feb. 3, I realized he was right.

William J. Allen III (Col ’85)

Lieutenant Colonel, Air Force Reserve

Afghanistan: February 2002 – December 2003,

Iraq: May 2003 – November 2006

After 9-11, I volunteered as a C-17 Instructor and Flight Examiner in the Air Force Reserve to fly in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and take time off from my full time job of flying as a Captain for United Parcel Service. I spent most of 2002 and early 2003 flying back and forth between the Europe and Afghanistan to support our troops in theatre. I ended up volunteering to fly one of the initial flights into Islamabad, Pakistan after 9-11 to deliver aid to refugees flowing into Pakistan and I flew the initial C-17 flight into Kandahar, Afghanistan when it fell to the coalition. It was truly a battle against fatigue more than anything else, because many of our days flying were in excess of 24 hours with aerial refueling, de-conflicting with other aircraft and operations in the area, Night Vision Goggle operations, etc. I was called to active-duty in April 2003 to assist with Operation Iraqi Freedom and flew for approximately a year full time into both Iraq and Afghanistan. I know I was much more fortunate than most in that my time in combat theater was always limited to several hours and then I’d be flying back to bases out of harm’s way. Many of my missions ended up being humanitarian in nature, which are always the most rewarding to me. One memorable mission involved airlifting casualties and KIAs out of Iraq. When the KIAs are transported, there is usually an escorting officer to overlook/officiate the movement of the bodies. When the escorting officer introduced himself (a Colonel), I asked if he wanted to ride up front for the flight as a courtesy. He said no, he wanted to ride in back with his son-in-law. At that point he broke down and stated, “I just don’t know how I’m going to face my daughter.” It turned out he was escorting the body of his son-in-law, whom he had commanded in Iraq. That flight was the most somber of my career and it still haunts me. I was released from active-duty in April ’04 and continued to volunteer when I could up until last year, when I retired. I was glad to be able to serve and see all the things we had practiced for so many years in work so well and succeed.

Stacey Grum Koff (Col ’87)

Lieutenant Colonel

Iraq, 28th Combat Support Hospital (Baghad Ibn Sina Hospital): August 2007-February 2009

I am from CLAS 1987 and eventually attended medical school at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in 1997. I graduated with Ray Topp, who was also a classmate from UVA. Two years after completing a urology residency at Walter Reed, I was deployed to Baghdad, Iraq. I spent six months there serving as the only urologist and back-up general surgeon at the Ibn Sina Hospital in the green zone. It was a great surgical experience but hard to be away from family, kids and the United States. Thanks for including us in the UVA Magazine.

Allen Irish (Col ’75)

Colonel, US Army

Combined Joint Civil Military Operations Task Force (March 2002 -September 2002)

352d Civil Affairs Command/Coalition Provisional Authority (February 2003-January 2004)

US Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute (current)

I served in Afghanistan beginning in March 2002 as the Staff Judge Advocate for the Joint Civil Military Operations Task Force. This was an organization that was established after the onset of the war in Afghanistan to provide humanitarian assistance to the people of Afghanistan and to begin the rebuilding of Afghan society. I worked with the task force commander and my colleagues to begin the reconstruction process and to do so within the tight fiscal and legal constraints that were in place at the time. As one of the few lawyers in country, I also worked closely with the U.S. Embassy on a number of thorny international law issues. One of the more interesting tasks I undertook was to draft the guidelines under which USAID would place its personnel with our remote teams. This concept quickly evolved into the provincial reconstruction teams that have become the interagency focus of reconstruction and stabilization in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

I deployed to Kuwait in March 2003 and moved to Baghdad in April as the Chief, Economics and Commerce for the 352 Civil Affairs Command. We were working in support of the coalition efforts as well as in support of ORHA (the Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance), which soon transitioned to the Coalition Provisional Authority and Ambassador Jerry Bremer. My role was to lead a team of officers who were tasked with reestablishing governance in the economic sector. As such, we not only provided planning capabilities to the coalition headquarters, we also took direct responsibility for reestablishing the ministries of agriculture, planning, industry, and other economically oriented agencies. As many people may recall, many of the ministries had been looted and even destroyed in the immediate aftermath of the invasion of Iraq in early 2003, leaving records, programs, and personnel in disarray. We were immediately faced with enormous challenges, such as reestablishing the Iraqi civil service, identifying and paying government workers, ensuring the distribution of food (the existing regime had an elaborate system for providing food to the population that could not be shut down without consequences), etc. I eventually was asked by Ambassador Bremer to establish an environmental ministry (I work in environmental issues in Washington) and spent the second half of 2003, into early 2004, developing an environmental protection program in Iraq.

I was somewhat lucky to have been in Baghdad from the very beginning, in that we were able to travel fairly freely around the city and country. As a result, I was able to see most parts of Baghdad traveling around to various ministry offices around the capital, as well as provincial cities. Many of the areas where we traveled fairly freely (in soft-skinned vehicles) would have been extraordinarily dangerous later on as the threat from insurgents grew.

I have subsequently been able to put my experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq to good use in my current position at the Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pa.