The Way We Were: The ’20s and ’30s at UVA

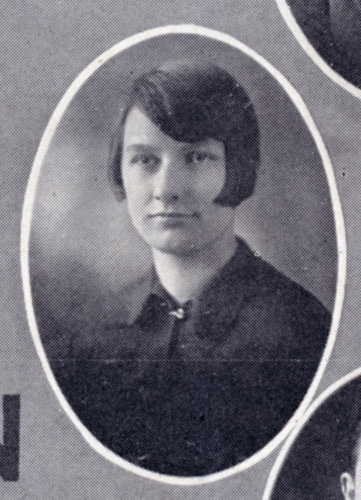

A conversation with Constance Page Daniel

Constance Page Daniel—whose father was mathematics professor mathematics professor James Morris Page, dean of the faculty—grew up on Grounds and earned an undergraduate degree from the University. She discusses what Charlottesville was like in the first half of the 20th century and reminisces about her experiences as a young woman at UVA.

V.M.: Tell us about how you came to be an undergraduate student at UVA.

This strange woman—she was quite rich—came by my father’s office one day, and said she had an interest in sending Southern women to Northern schools, just to let them see that there’s a different way of life. My father said, “If somebody else wants to educate my child, suits me all right.” So anyway, I went to Cornell. My benefactor lived in Ithaca, in a beautiful house, and she invited me to come and spend a week with her before I enrolled to see if I really liked it.

I had Carl Jung as one of my professors at Cornell. Yeah, but you could hardly understand him, his accent was so deep. He put on a good show, made it worthwhile.

V.M.: How long did you stay at Cornell?

Two years, and then the stock market crashed. And all of my friends that I’d made up there had to leave and go straight home, because they had no money. Their parents and friends were all jumping out of the windows from high towers and everything. It was just awful. I came home, and my father said, “We’re going to get you to be the first woman to graduate in the regular winter school.” Hundreds of women came to summer school to get their teaching certificates renewed, but he didn’t consider them students. He just considered them nuisances. So I went to college at UVA. I’d walk into a classroom and the students would all stomp. Stomping was their signal of derision. They didn’t want coeds at the University, and I was a woman, and I was at the University, and I had no business there. So they would stomp. And if I dared to answer the question or make a comment, they’d stomp again. So I was stomped my way through school. [laughs]

V.M.: How did that make you feel?

Pretty silly, but I also sort of laughed it off, and the students also laughed it off.

V.M.: How did you fit into the social life of the university?

Well, if you could breathe, if you were a woman and could breathe, you usually had four or five men following round behind you. So my social life was more than anyone could expect. [laughs]

V.M.: What were the social traditions?

Oh, the parties that I went to were all at fraternity houses. And they were forbidden to have parties, but they didn’t pay any attention to that. And so I’d go to the parties, and just have a good time chatting around. And there was never anything illegal or immoral going on. We behaved ourselves.

V.M.: Would you share a few memories of UVA?

At Mad Hall, they’d have afternoon tea dances around four o’clock in the afternoon. You’d go over there and you’d get the rush of your life, because there weren’t any women. The students were starved for women. We’d dance and have the best time.

I didn’t need a chaperone, because Diogenes, the night watchman, would come out to meet me and my date, and see us parked in our car, and he’d come and swing his lantern. And he’d say, “Miss Page, it’s 11 o’clock. If you don’t go in your house then we’ll have to call the dean.” I thought, “Oh, lord.” He never did call the dean.

My father was assigned a building on the Lawn, but he explained that he had six children, and he couldn’t have them running up and down the Lawn disturbing the students all the time. They built us a fine house out by the University cemetery, where it was very quiet.

My father would go to bed early and read until about midnight. And he wore a nightshirt, not pajamas. And one night he got a phone call from somebody over at the University Center that students are getting ready to riot, and they wanted him to be the object of the riot. And nobody knew why they were going to riot. They said the students weren’t going to riot if he would come and address them. My father said, “Well, I was in bed, you got me out of my bed, and I’m not accustomed to having business appointments at this hour of the night. But if they want to riot, tell them that they’ll have to bring the riot out here to me, because I’m not going to come to them.” Three or four hundred students stormed out to our house, crowded our lawn and stood there, and sang “The Good Old Song.” My father said, “All right boys, you’ve had your fun. I’m tired. Go on home and behave yourselves.” They went on home.

V.M.: How old were you then?

Oh, enough to get a big kick out of it. I’ve forgotten now. I guess I was in college.

The students had their meals at boarding houses because there was no regular dining room then. And they would come out to our house every Sunday after dinner, because there wouldn’t be any food at their fraternity house or boarding house. So they’d come out to our house and sit around. And you knew well they were going to have supper sometime. And they would be invited to supper. We had a German cook and housekeeper

V.M.: And you met your husband in Charlottesville?

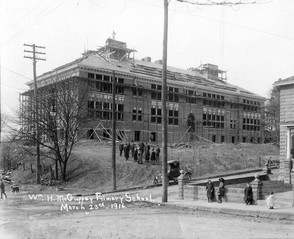

Well, I was sent to public school. McGuffey school had just been built, and so mother was horrified at the idea that I was going to a public school because her other children had all gone to private schools. And my father said, “Throughout life she’s going to meet all sorts of people, and she’s going to have to learn how to enjoy and appreciate other people’s opinions. And so she’s going to public school.” So I went to McGuffey school and Miss Burnley was my first grade teacher. And I remember her.

My husband’s family was in Korea. They were medical missionaries in Korea. But when the war broke out in 1917, they were required to come home. No foreign people over there. So that’s why he came back to Charlottesville.

He was in the classroom, and his name was Nelson Daniel (Engr ’32). And they’d call the roll, and we’d answer to the roll and I answered to my name and he answered to his, and we found out who we were. And there was no formal handshake or anything. We just sort of absorbed each other.

That was in second grade. You couldn’t start school until you were 7, so by that time I was 8 years old. And I knew a good thing when I saw it, and so I got him and hung onto him. We hated each other at first, because we were both thin and tall, and whenever the occasion, you know, little plays and parades and things, we were always paired off. And that was a big drag, because as I said, we didn’t like each other. We said, “We hate each other and let’s keep it that way.” And so anyway, that’s about the extent, the depth of our involvement.

V.M.: When did you realize you didn’t hate him anymore?

One night we were sitting in a car out by the University cemetery, waiting for Diogenes to come and make me go in the house. And every Sunday night or Sunday afternoon, Nelson would come out and we’d go walking round and round. And he’d ask me to marry him and I’d say no. And it didn’t make a difference. He’d still ask me every time and I’d say no. So anyway, this particular night we were sitting in the car and all of a sudden I said, “I think I will.” And he said, “You will what?” And I said, “Marry you.” Well, he went clean through the ceiling. And I thought, you know, he must really love me. And so I settled for that.

We were married at Grace Church at Cismont, where all of our family is married and buried. Grace Church, my great great great great grandfather or something gave the land for the church, paid for the stones and things to build it. And his name was Thomas Walker, and so they called it Walker’s Parish, which was appropriate. And so Walker Parish is still there, and if you go there you can see the graves of all my family that darn near fills the cemetery.

V.M.: How did getting the degree at UVA influence the rest of your life?

Golly. Well, I could read and write.

I’m an Episcopalian, and the rector at our church was Mr. Burke. So I went by Mr. Burke’s office one day and I said, “I need something to do. I’m sort of footloose.” And he said, “Good, I’ve got something for you to do.” And I said, “What?” And he said, “I want you to run this school.” And I said, “I can’t run the school.” And he said, “You have a degree, don’t you?” And I said yes. “And you can read and write, I assume?” And I said yes. He said, “Well, there’s no reason why you can’t run this school.” And I said, “Well, if you think so then I’ll take a shot at it.” So I must have taken a good shot at it.

V.M.: And that was at St. Andrew’s School in Newport News, right?

My job was the principal. You know, I didn’t believe in working my way up. I believed in starting at the top. So I started at the top, and I snowed everybody. Oh, they thought I was the smartest person in the world, and I didn’t anymore know what I was doing than a snow bird. I worked there for 13 or 14 years. They had plenty of chances to fire me.

V.M.: How have you seen Charlottesville change since you grew up here?

We had two horses, and a pony, and a mule at our house in the back yard on McCormick Road. Scott Stadium was our back pasture, and we had the animals back there.

For a long time, Lambeth Field was the only athletic field they had. And then Mr. Scott presented us with the stadium.

V.M.: Scott Stadium was built when you were living at home?

Yeah. It makes me feel as old as Methuselah.

V.M.: Did your sisters go to UVA?

[laughs] I had two sisters, my older sister went to St. Mary’s in North Carolina, which is a rather elegant girls’ school. Stayed a week and came home. Said she couldn’t stand it, didn’t have anything to eat but hot dogs. Well, the truth was that she missed all of her boys, missed having dates every five minutes. My other sister was not, shall we say, academic minded. She didn’t care two hoots for school. But anyway, she was sent to St. Anne’s, when it was a very exclusive girls’ school, down at the end of High Street, I guess. Down at the jumping off place down where the C&O station had its turntable thing, way down at the end of town. She’d play hooky most of the time. Nobody knew it except me.

V.M.: I thought children were always good back then.

Not always.

V.M.: What were the fashions when you were in school?

Blouses and skirt and we had great big bloomers. Big, full bloomers. If the people who lived then could see what they are wearing now, and the short shorts that hardly came up to here, they’d be horrified. Freshmen had to wear hats. That was the symbol of ignorance. They wore regular fedoras.

V.M.: What did you do for fun?

[laughs] What we didn’t do is most important. The main thing to do was to drive up to Afton and watch the sunrise.

Nelson had his father’s little roadster, his business car. And once, we got about half-way up to Afton, and Nelson said, “I’m too sleepy to drive. I’m going to have to pull over and rest a little while.” So he pulled over, and both of us went sound asleep, I mean just sound asleep. And then next thing we knew, opened our eyes, and that sun was shining, and the birds were singing. [laughs] Nelson said, “Uh oh.” And so we headed on to my house out by the cemetery, and our household help, three or four people, were just coming to work at that time. And Odie, our nursemaid who raised us, was there. And I got out of the car, and I said, “Odie, don’t you tell mother what time I got in.” She said, “No ma’am, I ain’t seen you at all.”

V.M.: Did prohibition affect the life of the University?

Well, I don’t know how it played for the rest of the place, but my father planted a vineyard, eight acres of all sorts of grapes. And we had grape wine everywhere. That was down at the farm, down behind the stables. And I remember the three kinds of grapes, Niagara, and the Concord, and something else. The Niagara were little white grapes, the Concords were purple grapes. People aged whiskey in Coca-Cola barrels. And so they put all of the whiskey and stuff down there and let it age, and oh boy, it got good. We kept all of it near the dining room. Sometimes we’d be eating and something would go, “Boom!” And I said, “Oh, another can of peaches exploded.”

And I can’t think of the favorite moonshiner’s name. It wasn’t Captain Mac, but it was something. Everybody knew who he was. You’d have some whiskey, and it would be rot gut. It would be as clear as water, and not fit to drink, really. And so we’d get a little barrel or something, and put the charcoal in it, and then put this white whiskey stuff, you know, with the charcoal in it, and drive all around all the rough roads, so that it would shake it and shake it and shake it. And by the time it got back, you had the finest whiskey you ever tasted. Sometimes we’d drive it all the way round a nine-mile circuit. Rio Road.

V.M.: So your husband went to work at the Newport News Ship Building and Dry Dock Company. And how was your life in Newport News different from Charlottesville?

It was like moving from heaven to hell. I was allowed five dollars a week to run the house on, buy the food, pay the maid, oh yes, I had to have a maid. I paid the man who did the man’s work around there. And that didn’t leave much out of the five dollars for us to spread. But anyway, we made out just fine, and Nelson actually put on about five pounds of weight. Nelson was 6 feet 6 inches tall, and weighed 150 pounds. And you know for some reason, they called him Slim.

V.M.: Did your life change when the war came?

World War II. Nelson didn’t go to war. He couldn’t because he was too tall. So he built submarines.

V.M.: Can you share some memories of Dean Page?

He spoke many languages. German. He spoke that fluently. And in his last illness he had a stroke. And he spoke German. And fortunately, I had taken some German in college, and that sort of guided me through it.

He taught mathematics. Mostly calculus. And something, I asked him if I thought I could take it. And he said no. And I said, “Why not?” And he said, “’Cause you haven’t got sense enough to understand it.” It was some branch of mathematics. I’ve forgotten what it was. Probably just simple arithmetic.

V.M.: Do you have any advice for the young women at the University now?

Put your sights on a guy that you’d like to marry, and hang on, and run him down.

V.M.: Any other memories of your student days?

We had two streetcar conductors. Mr. Maupin was nice, and Mr. Burkhead was just mean. And Mr. Maupin would see us coming around the chapel, and ring the bell, “clank clank clank,” like he was saying, “I’m waiting for you.” And so he would wait for us until we got there, and I thought that was good. And then Mr. Burkhead was there. He’d see us coming and he’d just speed up the streetcar. Probably laugh all the way downtown. Got off the streetcar and went over to Midway School, which is at the top of Vinegar Hill, and tried to behave myself in school.

Yeah, they had the Jefferson Theater, and the Lafayette Theater, and everybody called the Lafayette Theater the “laugh it off” theater, because apparently they just played reruns or something stupid. But the Jefferson Theater was the place to be, and that was good.

My best friend’s parents owned Timberlakes drugstore. And she could take one of her friends in to have an ice cream soda every day, but couldn’t treat but one person at a time, because otherwise they’d put them out of business. So we’d go in and have a chocolate milk. Not a chocolate milkshake, but just chocolate milk, a glass full of milk with chocolate pudding. Lord, it was heaven on earth.