Sorting Through Garbage

UVA professor tackles the complexities of transporting trash

Where does your garbage go? It’s a question that most Americans don’t think much about.

They also may not realize that, as a country, the U.S. produces the most trash on earth. In 2007, each American produced an average of 4.6 pounds of garbage per day, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. That adds up to 1,679 pounds a year. A family of four creates about 6,700 pounds of trash a year, more than the weight of a Chevy Suburban; and an individual would create the equivalent of 21 Suburbans over a lifetime.

To many Americans, that trash simply “goes away.” But its eventual destination rides on a squeaky wheel of economic, political, social and environmental decisions and uneasy tradeoffs.

Vivian E. Thomson (Grad ’97), an associate professor in UVA’s departments of politics and environmental sciences, is fascinated by trash. Peel back the top layer, she says, and what issues forth is ever more pungent. At the center of the stink is its paradoxical status as both pollution and commerce. Trash is publicly undesirable but commercially valuable.

This dichotomy is especially evident in Virginia. The state is a bona fide trash capital, the second biggest importer of trash from other states. Thomson focuses on Virginia in her new book, Garbage In, Garbage Out: Solving the Problems with Long-Distance Trash Transport. It examines the movement of waste across state lines to frame larger problems—“How much trash we generate; who gets to regulate it, and who must tolerate its dumping grounds,” she writes.

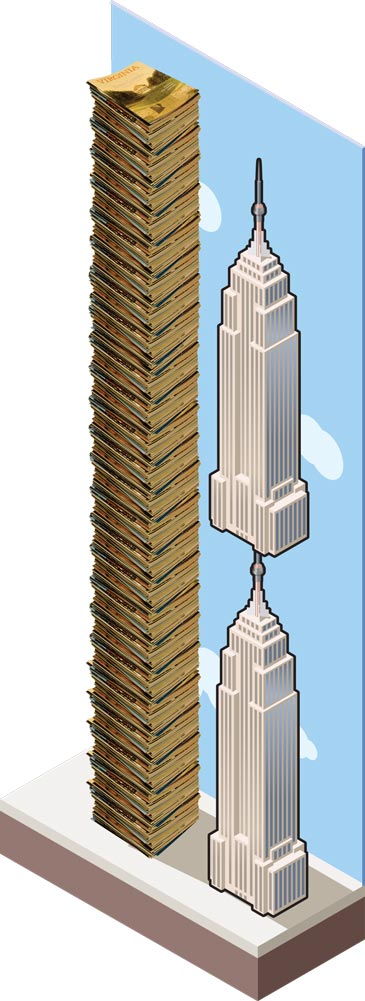

Trash is on the move as never before. By truck, rail and barge, it often travels hundreds of miles, headed for a “mega-landfill,” a private, regional waste disposal facility where the economies of scale are staggering. Virginia has 15 mega-landfills; one recently built facility “could in theory grow to be 500 feet tall, which is the height of the Washington Monument,” Thomson writes, “and could extend across an area equal to a thousand football fields.”

New environmental standards implemented in the early 1990s forced many municipalities to close their local dumps. Exporting trash to larger, privately run landfills became a cheaper option than upgrading public facilities to meet stringent state and federal regulations. Today, only a few multi-national corporations handle a substantial portion of the waste in the U.S.

Virginia’s current landfill capacity exceeds 20 years, according to the state Department of Environmental Quality. In past years, however, it has dipped below that mark. “The economy oftentimes plays a role in the rate of solid waste disposal, i.e., more waste disposal during prosperous economic conditions,” says Jeffrey Steers, the DEQ’s waste division director.

Two-thirds of Virginia’s mega-landfills are concentrated in southeast Virginia. Thomson notes that these facilities are disproportionately in areas that are rural and poor. But sometimes these communities have invited trash into their backyards, hailing it as economic development.

“Local officials have accepted these landfills as money machines. On the other hand, are they really? What will happen down the road when they begin to leak, because they will?” Thomson asks. “Who will pay?”

At the state level, trash is viewed as an “unmitigated environmental liability,” Thomson writes, “with no economically redeeming qualities.” Many former landfills, such as one in Selma, Va., are Superfund sites with cleanup running into millions of dollars.

“Our biggest challenge exists in advancing the cleanup of contaminated groundwater at old, closed municipally owned landfills,” says Steers, “where there is no current revenue stream to support corrective action.” But in Virginia, measures to impose a tax on garbage to establish an environmental cleanup fund have failed. The perception persists that throwing stuff away has no cost.

Thomson’s trash obsession dates to her days as a young policy analyst with the Environmental Protection Agency in the 1980s. She worked in San Francisco and later Washington, D.C., where her job was to monitor air pollution policy. At the time, she says, no one was paying much attention to air contamination caused by landfills. She and fellow analyst Susan Thorneloe began touring these facilities and found something to be worried about: high levels of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, and carcinogens like benzene and vinyl chloride. Their findings led to new comprehensive air pollution regulations for landfills.

“I was really struck by the variety of things that Americans throw away,” recalls Thomson, an eight-year member and former vice chair of the State Air Pollution Control Board. “The germ for the book was definitely planted at that point.”

In 2001, she spent a year at the University of Southern Denmark as a Fulbright professor of American studies, which exposed her to a very different sensibility. The Danes embrace what she calls “energy frugality.” They limit their energy consumption, bike rather than drive, live in smaller houses and pay exorbitant taxes on oil and gas. Living modestly is an ingrained Danish habit, Thomson says, yet they consistently top happiness surveys.

But Americans don’t have to become like the Danes to achieve high recycling rates, she says. There are many models throughout the country of aggressive programs that are yielding results. It often comes down to a matter of political will. Even modest solutions can make a big difference in the long run, and “small incentives can go a long way to changing behavior,” she adds. Cities like Richmond and Falls Church in Virginia and Los Angeles and San Francisco in California have achieved recycling rates above 50 percent; San Francisco aims to send zero waste to landfills by 2020.

As founder and director of UVA’s Environmental Thought and Practice B.A. Program, Thomson urges her students to think about environmental problems from an interdisciplinary perspective. The study of trash has provided all this and more. This past semester, Thomson asked the fourth-years in the ETP program to tackle a real-world problem: “El Dompe,” a notorious, noxious landfill in Colon, Panama. Begun by the U.S. in the 1940s when it occupied the Canal Zone, the 27-acre dump is situated in an impoverished region that gets 120 inches of rainfall a year. “It’s an open, festering, toxic mess,” says Thomson. During a recent site visit, a methane fire raged uncontrolled.

The choice of Panama wasn’t arbitrary. Thomson directs the University’s Panama Initiative, a partnership with various institutions in Panama to promote collaborative research and teaching relating to sustainable development. “Land use changes in the Canal Zone since Panama took over control are a big issue now,” says Janet Herman, a UVA environmental sciences professor who contributed her expertise in water quality issues to the El Dompe project. “There’s lots of development pressure and public health concerns.”

With the support of a Harper Endowment grant through the College of Arts & Sciences, the students set to work analyzing El Dompe, assessing the environmental and economic implications of three sets of options, ranging from maintaining the status quo to building a waste-to-energy incinerator (burning trash to generate electricity) and instituting recycling and composting operations. For this huge undertaking, the EPA’s Thorneloe provided key (and gratis) support through its contractor, RTI International, running a sophisticated computer model that enabled the students to compare the life-cycle implications of various waste-management scenarios. In addition, Stanley Heckadon Moreno, a noted Panamanian environmental scientist with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, visited UVA to work with the students.

This past June, a small group traveled to Colon to deliver the highlights of their 75-page report on El Dompe.

“Our attitude wasn’t to look for the right answer,” says Courtney Mallow (Col ’10), who helped give the presentation in Spanish. “We were looking at several options for the people of Colon. It’s their community and their dump. We wanted them to be informed so that they would be able to make the best decision.”

They had modest hopes for their reception. “I expected five people,” Thomson admits. “There were over 100.” The mayor and city council attended, as did a vocal contingent of Panamanian university students who held a demonstration, carrying signs exhorting officials to fix their trash problem. “It was really energizing to see people passionate about it,” Mallow says.

Panamanians, as well as U.S. residents, can look to some European Union nations and Japan for models of public policy to reduce trash, but the onus is on each of us.

“As a nation, we must take greater responsibility for the amount of trash we generate and for its adverse impacts on human health and the environment,” Thomson writes. “In so doing we will solve the real problems with long-distance trash transport.”

Problems and Solutions

Trash Stats

- Twenty-five percent of all trash disposed or incinerated in the U.S. is transported across state lines.

- In 2007, Virginia accepted 15.9 million tons of trash, 35 percent of which was imported.

- An estimated 10,000 acres, or 15 square miles, has been permitted as landfills in Virginia (an area slighter larger than the city of Charlottesville, which covers 10 square miles).

- The average American generates at least 29 percent more municipal solid waste than the average counterpart in Europe and Japan.

- Americans make 73 percent more trash by weight than they did in 1960 (2006).

- In 2005-06, the national recycling rate in the U.S. was 33 percent while that in the EU-15 Member States was 43 percent. UVA’s overall recycling rate in 2007 was 38.8 percent; the average for the state is also 38 percent.

Sources: Garbage In, Garbage Out; UVA Recycling Program; Virginia Department of Environmental Quality

*Thomson’s book was published in 2009 using data published through 2007.

The Growing Tide of Electronic Waste

In the 21st century, electronic waste “surely looms as one of the newest and most daunting problems,” says Vivian Thomson. Electronic waste makes up 2 percent of our waste stream and is likely to rise. Televisions and computer tubes contain toxic metals such as lead, cadmium and mercury. But they also contain precious metals—gold, silver and platinum—that could be reused rather than buried underground.

- Americans own more than 3 billion pieces of electronic equipment.

- 20 million TVs in the U.S. become outdated every year.

- In 2005, an estimated 1.5 million to 1.9 million tons of electronic waste were discarded.

- 100 million computers and monitors became obsolete in 2003, a three-fold increase over 1997 levels.

- In 2005, there were an estimated half a billion unwanted cell phones in people’s homes. In terms of precious metals, their combined worth was about $300 million.

- An estimated 80 percent of the energy consumed in the life cycle of a computer (including manufacturing) could be saved through reuse.

- As of 2007, 14 states had adopted e-waste legislation or regulatory programs that include bans on landfilling or incinerating electronic waste, and consumer fees to finance recycling and reuse. At the federal level, there are currently no regulations controlling electronic waste, although EPA administrator Lisa Jackson said in August that a new international priority for the agency will be cleaning up e-waste.

- In the European Union, member states are required to establish take-back systems for electronic waste.

Putting a Lid on It

Vivian Thomson proposes a two-pronged solution for addressing trash problems. She suggests that the Environmental Protection Agency should:

- Set national waste diversion goals

- Better promote pay-as-you-throw programs

- Regulate the disposal of electronic products and household hazardous waste

- Study the possibility of instituting extended producer responsibility programs for common types of non-hazardous waste, like packaging

To protect future generations and vulnerable communities, she also recommends that the federal government:

- Assess a new small national fee on garbage ($1 to $5 per person per year) to pay for current and future contamination and discourage waste production

- Establish new procedural safeguards for communities that have accepted or might accept new waste disposal facilities

- Write federal guidelines on compensation for landfill or incinerator host communities

- Adopt some version of the proximity principle (that waste disposal should be as close to home as possible so it won’t be dumped in someone else’s backyard)