In the Age of Slavery

UVA examines role of enslaved laborers in tribute to bell ringer Henry Martin

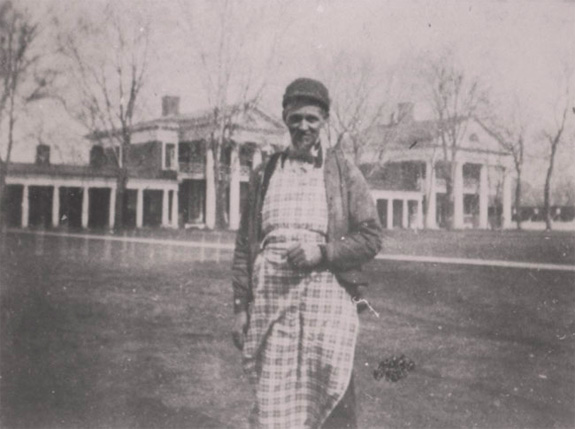

When members of the University community hear the bell toll the hour on Grounds these days, they can thank an automated system that is a nicety rather than a necessity in the information age. For more than 50 years, however, the responsibility of marking each hour fell to Henry Martin, a man born into slavery who became a beloved figure among students and faculty during his time as the University’s bell ringer. “It truly was a lifetime of service to the needs and interests of the University of Virginia,” says Coy Barefoot (Grad ’97), author of The Corner: A History of Student Life at the University of Virginia. In Martin’s day, the Rotunda bell could be heard far beyond the Academical Village and was a familiar sound to area residents. “In a real sense, Henry Martin was the hub of the wheel for the University community and for Charlottesville.”

Martin’s service and legacy will be recalled Jan. 25 in a lunchtime panel discussion and later at a service in the Rotunda as part of UVA’s commemoration of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Barefoot and other panelists also will discuss the broader role of enslaved laborers at the University. “Conversations about the legacy of Henry Martin come at a time when several universities around the country are looking at the role that slaves and former slaves played in the building of universities and local communities,” says Derrick P. Alridge, a Curry School professor who will be the panel’s moderator. “So now is a ripe time to examine the legacy of slaves and former slaves to various institutions in this country.” Two other institutions are collaborating on similar examinations of slavery. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History have partnered on an exhibit, “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty,” set to open on Jan. 27. In addition, Monticello plans a multimedia exhibit beginning in February that will focus on historians’ work to interpret and restore Mulberry Row, the hub of 21 dwellings where enslaved and free workers went about their daily labors at Jefferson’s Albemarle County home. Computer animation, apps for mobile devices, a website—all will be used in “Landscape of Slavery: Mulberry Row at Monticello.” “We don’t shy away from slavery, we talk about slavery because we know that it’s fundamentally important to understanding Jefferson and understanding America,” Susan Stein, a senior curator at Monticello, told the Associated Press.

Henry Martin provided a link between the University and its founder. According to oral history, Martin was born at Monticello on July 4, 1826—the day Jefferson died. Though sold as a slave to the family of George Carr, Martin was freed by the time he was hired as the University’s bell ringer and janitor in 1847, according to research by Catherine Neale (Col ’06) for her undergraduate honors thesis. Martin routinely awoke at 4 a.m. to tend to his responsibilities, which he took seriously. “I [was] as true to that bell as to my God,” Martin said in a 1914 interview in Corks and Curls. Indeed, Dr. David M.R. Culbreth, writing in 1908, recalled, “In my experience I do not recall the bell pealing out of time, and yet that must have occurred to prove human error and fallibility.”

Martin rang the bell to spread the alarm when the first wisps of smoke were discovered in the Rotunda fire of 1895. That catastrophe forced the bell ringing to be moved to the University Chapel. By Martin’s retirement in 1909, he was a local icon, beloved for his devotion and his familiarity with members of the University. At his death at age 89 in 1915, the student newspaper said, “He was known personally to more alumni than any living man,” and “is said to have known by name ... every student who resided here during his long service as bell ringer.” Corey D.B. Walker, a panel member and former UVA professor who now is a professor and chair of the department of Africana studies at Brown University, says that without detracting from Martin’s contributions and service, it’s important to look beyond one personality. “We have to remember, these people were enslaved. No matter how much we want to romanticize it, they did not control their destiny,” Walker says. “The problem of making the assertion that he was wonderful and a beloved figure belies the very violence of the institution of chattel slavery.” The observations and discussions at UVA, as well as the exhibits at Monticello and the Smithsonian, provide opportunities to use the past as a lantern for the future. “This becomes an opening for us to have a conversation,” Walker says, “but we have to be very careful with it, not to engage in a way that the past is behind us, but to engage in how the past continues to challenge the ways in which we want to develop our nation and our world.”

Events

Jan. 25: “The Enduring Legacy of Henry Martin and Other Enslaved Laborers at UVA” at noon, the Harrison Institute auditorium. At 5:30 p.m., an event in the Rotunda Dome Room will be held to honor Martin. Details

Jan. 27–Oct. 14: “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty,” at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, on the National Mall, Washington, D.C. Details

Jan. 27: “Getting Word: African American Families of Monticello,” a website to be launched at Monticello showcasing oral histories of slaves there. Details

Feb. 17: “Landscape of Slavery: Mulberry Row at Monticello,” exhibit opens at Monticello in Albemarle County. Details